Off-Site Exhibition: John Outterbridge: Rag Man

- – This is a past exhibition

After growing up in the South and studying art in Chicago, John Outterbridge (b. 1933 Greenville, NC) moved to Los Angeles in 1963 and became a seminal figure in the California assemblage movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Like such peers as Noah Purifoy and John Riddle, he was deeply impacted by the Watts rebellion in 1965 and began to incorporate the detritus that littered the streets into his work. Raised in a community steeped in creativity as a part of everyday life and characterized by a strong ethos to save and recycle, Outterbridge has been composing sculpture from found and discarded materials and debris—including rags, rubber, and scrap metal—for more than 50 years. Also a committed educator and social activist, he cofounded the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton, where he was artistic director from 1969 to 1975 and was director of the Watts Towers Art Center from 1975 to 1992. The exhibition will focus on works made since 2000 composed of materials such as tools, twigs, bone, and hair—including a recent series called Rag and Bag Idiom—that recall ancient healing rituals or talismanic objects while also engaging in direct dialogue with the work of artists such as Edward Kienholz, Senga Nengudi, Noah Purifoy, and Robert Rauschenberg. Outterbridge’s work was featured in several exhibitions in the citywide initiative Pacific Standard Time in 2011-2012, including the Hammer’s Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980, and he had his most recent solo show in Los Angeles at LA>John Outterbridge is organized by Hammer Museum senior curator Anne Ellegood with assistant curator Jamillah James.

Art + Practice is located at 4339 Leimert Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90008.

Biography

John Outterbridge was born in Greenville, North Carolina, in 1933. He studied at the American Academy of Art in Chicago in the 1950s and moved to Los Angeles in 1963. In 1994 he received an honorary doctorate of fine arts from Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles. He cofounded the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton, where he was artistic director from 1969 to 1975, and was director of the Watts Towers Art Center from 1975 to 1992. Outterbridge’s work has been included in several group exhibitions, such as When Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American Self, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (2014); The Encyclopedic Palace, 55th Venice Biennale (2013); Blues for Smoke, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2013); Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2011); Los Angeles 1955–1985: Birth of an Art Capital, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2006); São Paulo Bienal (1994); INSITE 94, San Diego and Tijuana (1994); and Forty Years of California Assemblage, UCLA Wight Art Gallery (1989). A survey of his work was presented in 1993 at the African American Museum in Los Angeles, and he had a solo exhibition at LA><ART, Los Angeles, in 2011. In the 1970s and 1980s he showed with Brockman Gallery in Leimert Park, and he is now represented by Tilton Gallery in New York. In 2013 Outterbridge received the Governors’ Award for Outstanding Service to Artists from the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and in 2012 he received the California African American Museum Lifetime Achievement Award.

Essay

Art, as a process, might teach one to care in a different way and to see. —John Outterbridge

John Outterbridge: Rag Man

In the more than fifty years since he moved to Los Angeles, John Outterbridge (b. 1933, Greenville, NC) has been a prominent figure within the local art scene, leaving his mark from Pasadena to Leimert Park to Watts as an artist, an educator, and an activist. Soon after arriving in the city in 1963, he began working as an educator and art handler at the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum), where he met artists such as Mark di Suvero, Robert Rauschenberg, and Richard Serra, who were invited to exhibit there by the museum’s iconoclastic young director and curator, Walter Hopps. Outterbridge also quickly found a community of local artists who shared his aesthetic sensibility and belief in the power of art to impact people’s lives, including Alonzo and Dale Davis (who founded Brockman Gallery in 1967), Melvin Edwards, David Hammons, Noah Purifoy, John Riddle, and Betye Saar. Their shared interest in assemblage techniques was further catalyzed by the Watts rebellion of 1965, which brought visibility to the injustices experienced by the African American communities of Los Angeles and also provided an important source of sculptural materials in the form of the detritus that littered the streets following the six days of unrest. Collectively this group came to be identified with the California assemblage movement, which emerged in the 1950s with the work of artists like George Herms and Edward Kienholz and is considered one of the most vital artistic developments on the West Coast during this period.

Outterbridge’s engagement with found materials began long before his move to Los Angeles. Raised in a culturally rich community steeped in vernacular forms of creativity—bottle trees and fences decorated with eggshells—and characterized by a strong ethos of saving and recycling, Outterbridge was quite literally surrounded by used and discarded objects valued for their potential afterlife. His father was a “junkster” who collected and sold all kinds of things, storing them in the backyard. As a child Outterbridge knew people who accumulated and peddled rags—so-called ragmen—and one of his earliest bodies of work is the Rag Man series. While many of these works from the 1970s have been destroyed or lost, the exhibition includes two superb examples: Case in Point (ca. 1970), which resembles a bundle of rolled textiles held together with straps and buckles with the tag “packages travel like people,” and Jive Ass Bird (1971), composed of variously sized stuffed and sewn textile “bags” punctuated with the stars and stripes of the American flag. A recurring motif in Outterbridge’s work, the flag is also integral to Déjà Vu-Do (1979–92) and later works likes I Mus Speak (2008). In Search of the Missing Mule (1993), part of a series of works that consider African American labor within the history of American expansion, features a tall figure wearing a blindfold made of a torn and bleached American flag. Outterbridge sees the mule as a symbol for the black body, courageously searching for overdue absolute freedom.

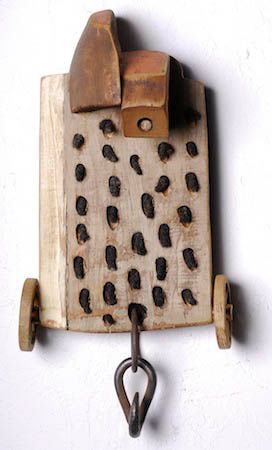

Déjà Vu-Do is from the artist’s Ethnic Heritage Group, a series of thirty-seven sculptures that examine the doll figure both as a ubiquitous toy for children and as an idol that personifies something (or someone) significant and esteemed within a culture. Inspired in part by the stories told by Outterbridge’s elders when he was a child, the Ethnic Heritage Group gave him an opportunity to further research folk medicine, voodoo, and cultural superstitions in both the United States and Africa. These interests have remained central to his practice and extend into the large group of modestly scaled wall works made between 2002 and 2011, which contain not only the metal tool parts and carved wood found in much of his oeuvre but also symbolically loaded materials such as human hair and the asafetida bags traditionally worn on the body to ward off disease. The most recent works included in the exhibition, the Rag and Bag Idiom series (2012), feature Outterbridge’s characteristic found textiles painted an array of vibrant colors. Simultaneously culturally and historically specific and devoted to the idea that human experiences provide a universal perspective, these works reflect back on the more abstract works from his Rag Man series while also contributing to significant investigations in the field of contemporary art more broadly, including the interface between painting and sculpture and the role of everyday life in the language of abstraction.

Not only has Outterbridge made important and compelling contributions to the history of contemporary art in Los Angeles—influencing a number of younger artists in the process—but he has also been a vital and steadfast part of the community. He was active in the civil rights movement, and his activism extended into the art world. He was a member of the Black Artists Association and worked with the Black Arts Council to confront local institutions about the lack of opportunities for artists of color. Also a committed educator, he cofounded the Communicative Arts Academy in Compton, where he was artistic director from 1969 to 1975, and he was the director of the Watts Towers Art Center from 1975 to 1992. Inspired and energized by his surroundings, he considers his studio to exist “everywhere.” Like many of his peers, especially the late Noah Purifoy, a close friend with whom he had a strong intellectual connection, Outterbridge believes that art can be used as a tool to create social change. They recognized that the struggles with which they were engaged would change American history, and they had, as Outterbridge puts it, “a sense of belonging to the history of America.”

The Hammer Museum at Art + Practice is a Public Engagement Partnership supported by a grant from the James Irvine Foundation.

Special thanks to Tilton Gallery, New York.