Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker

- – This is a past exhibition

Dutch artist Lily van der Stokker has been making bold, colorful large-scale wall paintings for more than twenty years. The artist applies colors ranging from soft pastels to bright fluorescents—sometimes in playful and visually arresting plaid patterns or all-over flower motifs—to amorphous soft-edged forms that inhabit the space like friendly oversized visitors. Witty texts added alongside van der Stokker’s forms complicate their first impression as the cartoony doodles of an adolescent or mere decorative ornamentation. Invoking the platitudes of polite society with expressions like “Best regards” or “Wonderful” or touching upon the realities that impact all our lives, from love to money to aging, with phrases like “Transfer the money to me” or “Only yelling older women in here, nothing to sell,” van der Stokker makes evident the power dynamics at work within seemingly innocuous spaces. Van der Stokker argues for the role of pleasure in aesthetic experience, finding alliances between beauty and intellect, playfulness and criticality.

Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker is organized by senior curator, Anne Ellegood with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant.

Biography

Lily van der Stokker (b. 1954, Den Bosch, Netherlands) lives and works in Amsterdam and New York City. She earned a degree in drawing and textiles from R.K. Scholengemeenschap St. Dionysus, Tilburg, and a second degree in monumental design and painting from the Academy of Art and Design St. Joost, Breda. A practicing artist for several decades, Van der Stokker has had solo exhibitions at Galerie Air de Paris, Paris (2014, 2005, 2000); Koenig & Clinton, New York (2014); New Museum, New York (2013); kaufmann repetto, Milan (2012, 2010, 2005, 2002); Tate St. Ives, Cornwall (2012); Leo Koenig, New York (2010); Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands (2005–7); and Museum Ludwig, Cologne (2003). Her work has been presented in numerous group exhibitions at international venues, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2011); Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, Netherlands (2011); South London Gallery (2010); Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Grenoble, France (2009), and De Appel, Amsterdam (2008). Van der Stokker has undertaken two large-scale public commissions. In 2000 she created The Pink Building, for which she painted the entire exterior and roof of a building for the World’s Fair in Hannover, Germany, and she designed a large ceramic teapot, Celestial Teapot, for the roof of a high-rise shopping center in Utrecht, Netherlands, in 2013.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

Unless you happened to be outside the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1973, when Mierle Laderman Ukeles spent four hours scrubbing the stairs leading to the museum’s main entrance, or you attended the opening of Janine Antoni’s exhibition at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in London in 1993, when the artist got on her hands and knees and mopped the floor with her hair, it is unlikely that you’ve entered a museum or gallery to be confronted by the quotidian subject of cleaning and maintaining the spaces in which we live and work. Far from spectacular or glamorous, the predictably dull, and at times unseemly, demands of everyday life that continually require our time and attention are still largely considered separate from art. To make them the subject of art is to challenge the traditional separation between intellectual endeavors and the body, between the sacrosanct realm of art and culture and the ultimately equalizing domain of daily life. Efforts to collapse the barrier between art and life during the past half century are often associated with the material innovations of artists such as Robert Rauschenberg—with his rejection of notions of mastery and craftsmanship and insistence on bringing everyday materials into his work, like his bed, the morning newspaper, or an old tire—and the enactment of ordinary daily rituals like eating and drinking in the “happenings” of Allan Kaprow and others. But feminist artists have played the largest role in pushing back against the idea that subject matter related to domestic space, personal life, or emotional vulnerability is too frivolous and banal for the purview of art. In groundbreaking works from the 1970s like Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79) and Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), the tenets of conceptual art—with its integration of language and image, its embrace of photography and the video camera, and its unfolding over time and space—are enmeshed with questions of subjectivity, the body, and indeed, emotional affect, subjects generally avoided by an earlier generation of conceptual artists.

Since the late 1980s the Dutch artist Lily van der Stokker has been making large-scale wall paintings that unashamedly and exuberantly bring just such “inappropriate” topics into the public realm of art, often combining short, aphoristic texts with colorful, cheerful, soft forms and repeated patterns. Van der Stokker is fully committed to the liberating potential of integrating “high” art with commonplace and familiar aspects of our private lives. It was a radical gesture for her to carve out this niche for herself at a time when many women artists in the United States were adopting strategies of appropriation, producing works that were critical yet often cool in tone and intellectually rigorous, and when popinfluenced painting rooted in graphic languages and bright colors was typically associated with male painters like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Although Van der Stokker moved to New York City in 1983, she was raised and received her art education in the Netherlands (she continues to split her time between New York and Amsterdam), and in the early years of her career, women artists had little visibility in her home country, and questions of gender and feminism were essentially absent from works of art. She was well aware of the wall drawings of artists like Mel Bochner, Sol LeWitt, and Lawrence Weiner and adopted elements of their practices, like the interface with architecture and the use of language, while rejecting many of the imperatives they established for making their work in favor of creating her own highly original language and precise working methodologies. Van der Stokker embraced ideas of the decorative that underscored her interest in domestic space at a time when deconstructing institutional space was at its height. And she chose to paint her own wall drawings by hand—working from small colored pencil drawings that she faithfully follows and translates to a larger scale—rather than endorse the conceptualists’ argument that the essence of the work resides in the idea so that others can be enlisted to realize it.

Within this context, Van der Stokker deliberately chose to address emotional content in her drawings and wall paintings. And she found the use of text to be the most direct and powerful way to do so. One of her first drawing with language, which included simply the word sweet, was quickly followed by one that read, “I love you.” With humor and a sharp wit alongside a genuine fascination with that which has been deemed “feminine” both by the culture at large and by her personally, she has created wall paintings incorporating phrases such as “Women are very good at crying and I think they should be getting paid for it”; “I am so sorry I hurt you”; and “How sad for you,” insisting that emotions can be central to an art practice. Over the years she has taken up a number of additional subjects that she realized would be perceived suspiciously as not weighty enough for art, among them relationships, friendship, gossip, money, children, education, and housework (toilet paper even figured in a recent installation). As she has stated, “I choose my subject matter from topics apparently ‘forbidden’ in contemporary conceptual art, like family life, optimism and sweetness, and, by taking this radical position, I make my art approachable and controversial at the same time.”1

The duality articulated by Van der Stokker as “approachable and controversial” speaks to the core of what gives her work its tension, its energy, and ultimately its transgressiveness. Her incessant curlicues, cute flowers, and undeniably beguiling patterns, rendered in pastels and fluorescents that many would find cloying and vulgar, are at once totally sincere—she has repeatedly proclaimed her commitment to beauty and happiness—and willfully provocative. Her feminism resides in her awareness that, as she put it, “There’s no such thing as gender-neutral art.”2 And she insists that we recognize these ingrained biases through her bold approach to form and content, producing work that she knows will be judged by some as “girlie” and thus lacking in seriousness, intellect, and rigor. She has not backed down from her commitment to this position and has played the long game, as it were, and over time her aesthetic—often likened by critics to teenage doodles or the “decorative” realm of textile design—has come to feel incredibly radical. Indeed, with her adeptness at luring viewers with captivating (and seemingly innocuous) hand-painted illustrations, humorous texts, and sheer scale and then surprising them with content that is remarkably honest—by turns subversively friendly or bitingly critical and addressing such fraught subjects as power dynamics, social marginalization, and even the machinations of the art world—she has smartly aligned herself with the enduring and boundary-pushing strategies of satire, parody, and caricature. Like others who embrace these strategies, she is refreshingly unafraid to laugh at herself. Yet her work is far from cynical or ironic; on the contrary, she is dedicated to providing immense visual pleasure and communicating with the broadest public possible by touching on subjects and feelings that we have all experienced.

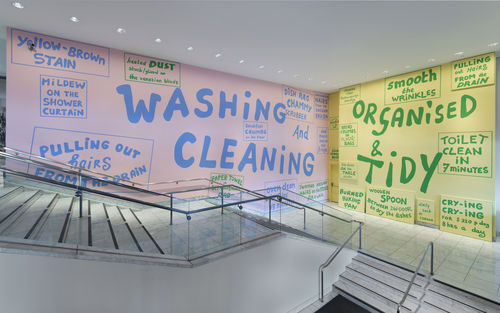

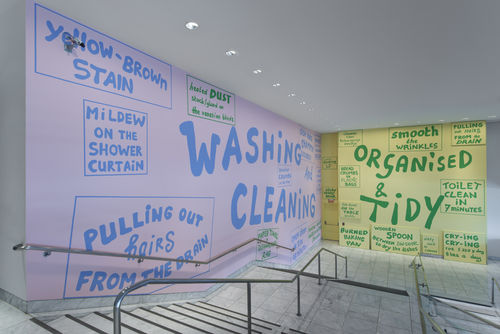

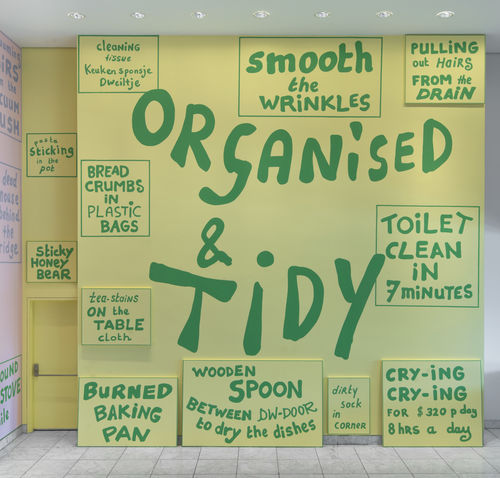

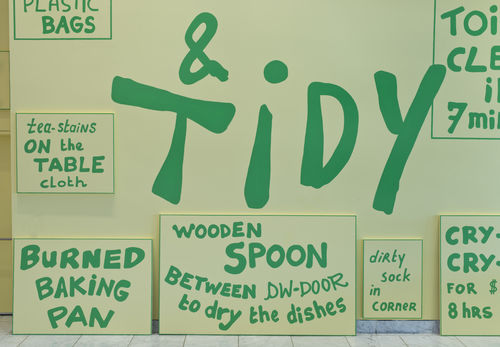

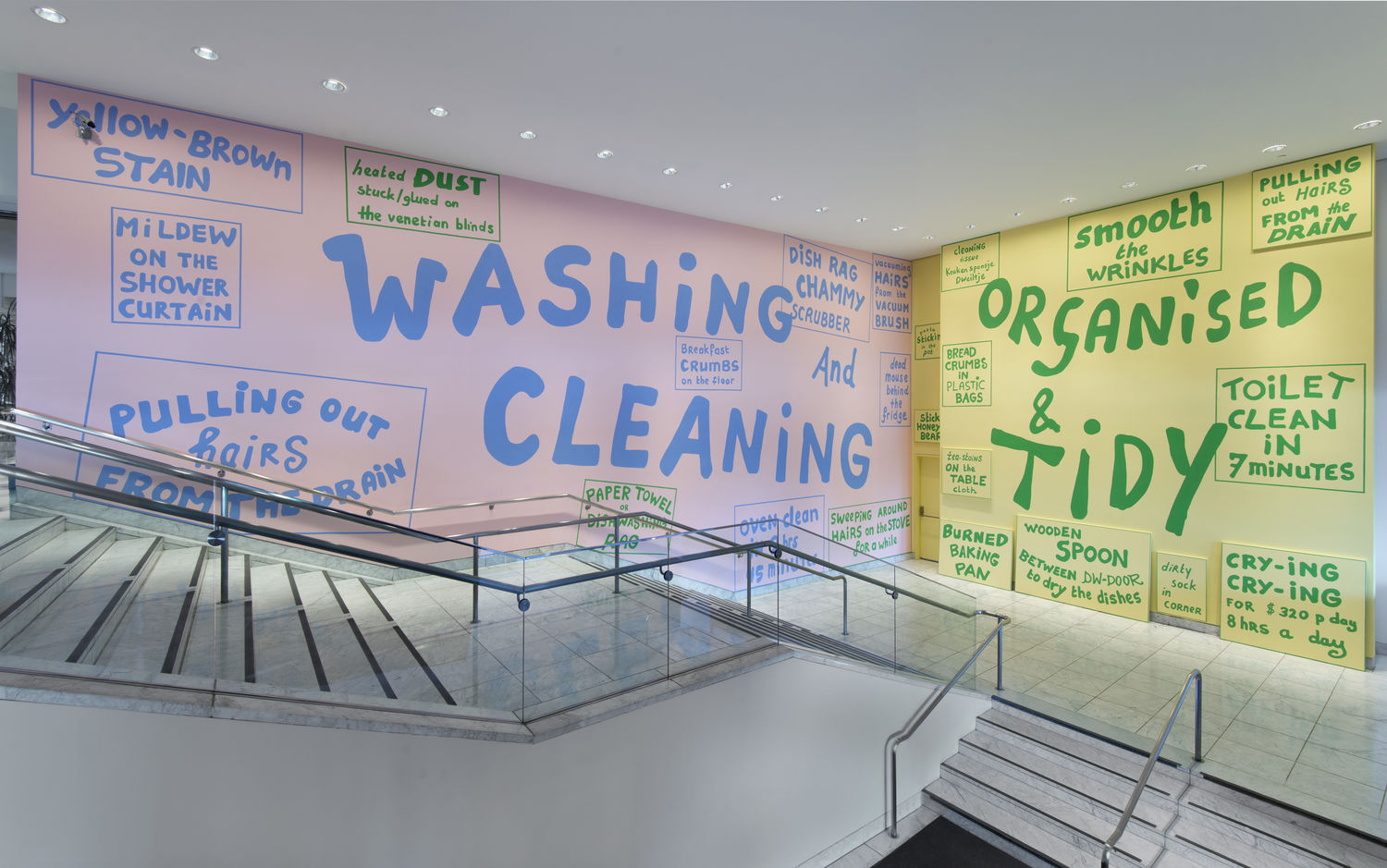

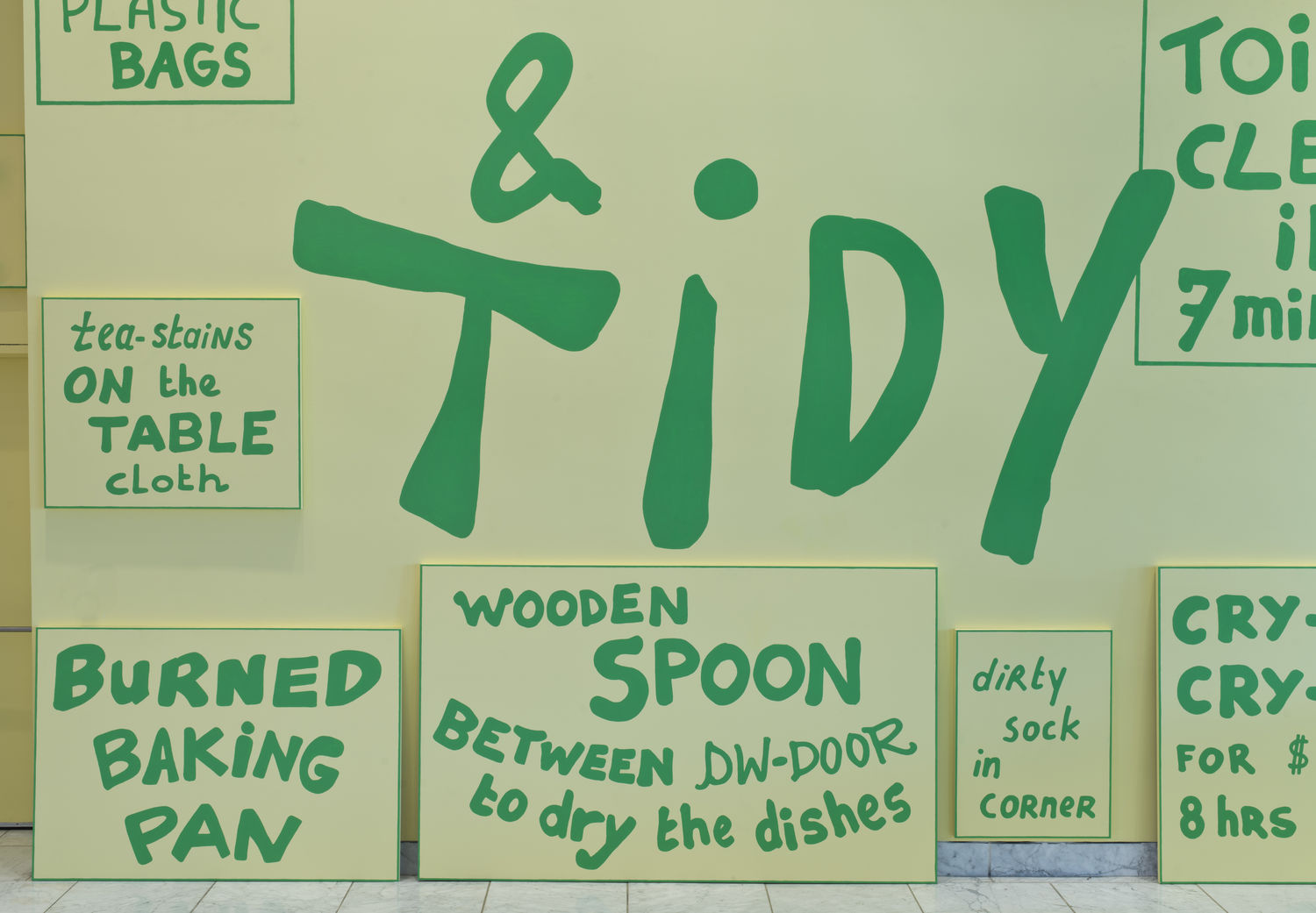

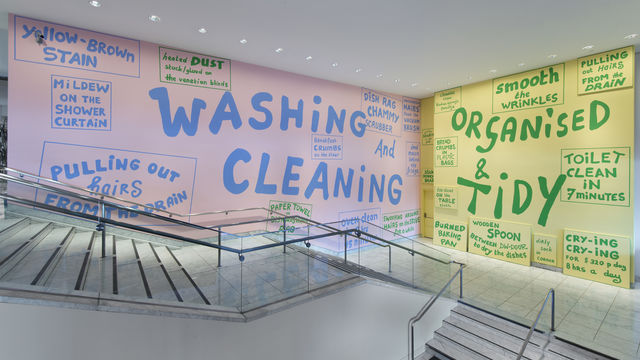

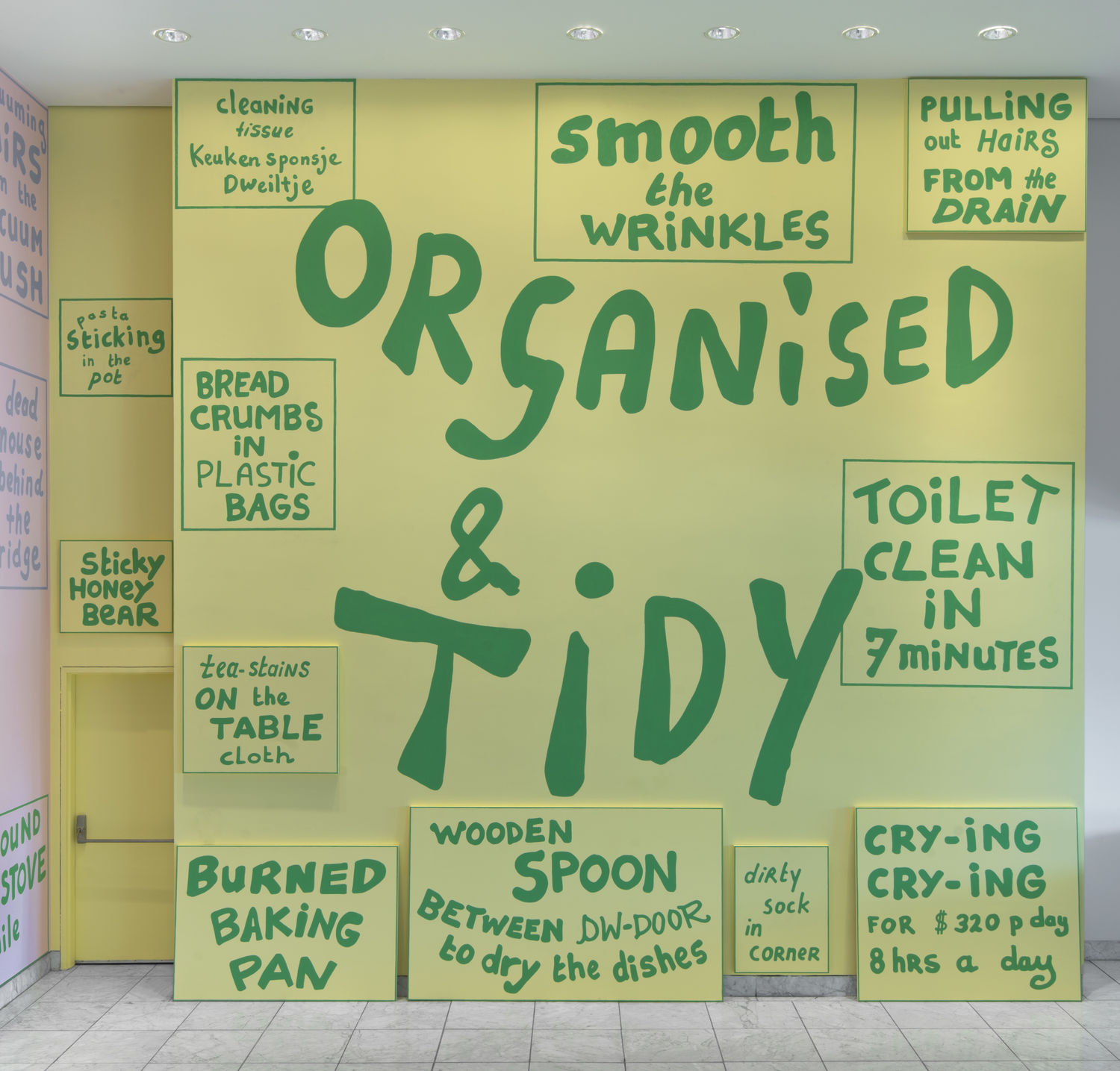

For her exhibition at the Hammer Museum, titled The Tidy Kitchen, Van der Stokker may have created her most political work to date. Eschewing imagery and pattern in favor of a heavily text-based approach, she brings the subject of housework and cleaning into the domain of the museum with an intensity and integrity on par with that of Ukeles, Kelly, and Rosler in the 1970s. The phrases “Washing and Cleaning” and “Organized and Tidy,” writ large across the expansive walls of the museum’s lobby, are surrounded by descriptions of objects and actions from the domestic sphere that are modestly charming or innocuous—“sticky honey bear” and “smooth the wrinkles”—or disgusting—“mildew on the shower curtain” and “dead mouse behind the fridge.” There is a humor to the sort of leveling that comes with an awareness that we all, at one time or another, have to remove hair from our shower drains. But this sense of shared experience is complicated by phrases that are more crassly commercial, like “oven clean in 2 hours 45 minutes,” reminding us of how we are constantly bombarded with ads for products claiming to make our lives easier and better. The space of domestic labor has long trafficked in the unacknowledged and unpaid labor of women, and van der Stokker takes the argument that women should be compensated for their skills and contributions one step further with the text “Crying Crying for $320 p day 8 hours a day,” which proposes women should be paid for expressing their emotions. Labor and gender issues quickly come to the fore, and a contemplation of domestic space extends into a consideration of public space, indeed the site in which visitors find themselves standing. Public institutions like museums, of course, require constant and diligent cleaning and safeguarding, and the efforts of those who maintain the physical integrity of these places often remains invisible and underacknowledged. As Van der Stokker describes it, the work “is almost a political demonstration for housecleaners. For me, it touches upon taboos in the art-world and celebrates domestic life.”3 In this work, we see her exceptional ability to finesse the complexities of her subjects with insight and simplicity. With a calming palette of pink, blue, green, and yellow, Van der Stokker both honors and celebrates cleaning as part of our daily lives and insists that art examine those things that we may prefer to keep hidden from view.

Notes

1. Lily van der Stokker, artist's statement sent to the author, November 9, 2014

2. Steel Stillman, “Lily van der Stokker: In the Studio” (interview), Art in America 102 (September 2014): 139.

3. Van der Stokker, email correspondence with the author, December 15, 2014.

Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker is organized by senior curator Anne Ellegood with MacKenzie Stevens, curatorial assistant.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a gift from Hope Warschaw and John Law. Generous support is also provided by the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy.

Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, the Decade Fund, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.

Hammer Projects: Lily van der Stokker is generously supported by the Mondriaan Fund.