Hammer Projects: Dara Friedman

- – This is a past exhibition

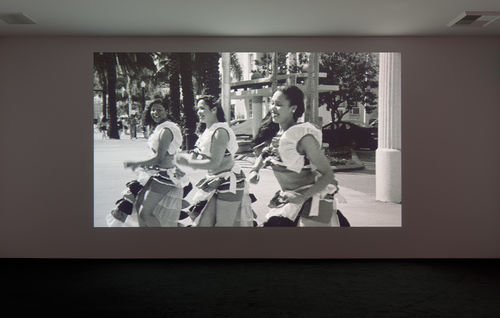

Dara Friedman explores notions of performativity, urban space, and the individual in the public sphere in her ebullient, poetic films and videos. For Dancer (2011), she enlisted Miami-based dancers of all stripes to dance through the city streets for the camera. Shot on 16mm black-and-white film and transferred to HD video, Dancer celebrates both the city and the medium of dance. With the city streets as a backdrop, dancers improvise, expressing the specificity of their styles and skills and making meaning through movement. Organized by Hammer senior curator Anne Ellegood, Hammer Projects: Dara Friedman is Friedman’s first exhibition in Los Angeles.

Biography

Dara Friedman was born in Bad Kreuznach, Germany in 1968. She lives in Miami, Florida. Friedman’s work has been the subject of one person exhibitions at venues such as Miami Art Museum, Miami, Florida (2012); Museum of Modern Art, New York (2010); The Kitchen, New York (2005); Site Santa Fe, Santa Fe (2001). Her work has been featured in thematic exhibitions internationally including Our Darkness, Kunstlerhaus Stuttgart, Stuttgard, Germany (2011); Greater New York, PS1, Long Island City (2010); Off the Wall: Part 1–Thirty Performative Actions, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and Serralves Museum, Porto, Portugal; Playing the City, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany (2009); As Heavy as the Heavens--Transformation of Gravity, Cultural City of Europe, Graz, Austria (2003); Videodrome ll, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York (2002); and Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2000).

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

When Dara Friedman was a young girl, she would obsessively analyze the plot of a movie to identify the gaps in its logic and to figure out where the story broke down or lost its flow. Her propensity for deconstruction was not, however, of the finger-pointing, “this makes no sense” type. Instead she was looking for the moment in the film when the rupture in its reasoning would seem to portend that the whole thing would fall apart but when instead, astoundingly, it all came together. Friedman has described this as the moment when she would “feel” the work and would somehow understand its meaning, its purpose, or its impact. For her, engaging in this type of exacting analysis did not suck the life out of the film or diminish her enjoyment of it but was a journey to find its life force. The process allowed her to locate an instance of heightened awareness, to identify the precise moment when thought progresses from the brain to the body. Friedman recognized this dynamic connection between mind and body—when to think something is also to understand it physically—at an early age. And this constant push and pull between the intellectual and the sensual, between a state of control and a state of release, has become the primary preoccupation of her filmmaking over the past several years.

Many of Friedman’s films bear witness to what can best be described as deeply human behavior, in which exhibitionism and vulnerability seem to merge in a state of symbiosis that suggests that one could not exist without the other. Yet while we may understand private space as the cocoon-like safety net for participating freely in all manner of behaviors, it is how we act in public that fascinates Friedman. She is as interested in the apparatus of film and its structural characteristics as she is in the content of what she shoots, and several of her early works sought to distill narrative to its very essence. By editing out anything deemed superfluous and embracing repetition, Friedman not only accelerated the story line to an evident climax, she also replicated the way life—and our memories of it—often unfolds. It is the decisive, vital moments marked by intense feelings that stick with us, that become the turning points in our lives, and that, as the artist has remarked, we play over and over again in our heads. Government Cut Freestyle (1998), for example, chronicles a group of adolescents at the Miami shore as they jump off a pier into the water below. A patient observer, Friedman presents her subjects sequentially, each occupied by the same activity, and draws our attention to both their shared exuberance and their individuality. A silent film that nonetheless resonates with a sense of rhythm and poetry, it captures the incredible fleeting sensation of letting go. For Romance (2001), she surreptitiously filmed couples kissing in a park in Rome. Presented in slow motion over thirty-one minutes, the film makes us privy to episodes of genuine intimacy, but rather than seeming salacious or even modestly voyeuristic, Friedman’s work feels incredibly generous, a reminder of the purity of our desires.

While indebted to the documentarian’s fidelity to filming real people engaged in everyday activities, Friedman is equally enamored of film’s ability to create magic. She was drawn to film for the way it combines the technical and the fantastical, for how it can transform the everyday into something remarkable. While she was initially influenced by her teacher, the Austrian structural filmmaker Peter Kubelka, her exposure to Jack Smith’s idiosyncratic storytelling also left an indelible imprint on her approach to her medium. Seemingly on opposite ends of the filmic spectrum—one measured and rational, the other frenzied and chaotic; one a masterful technician for whom precise aspects of the moving image become the primary investigation, the other a pioneer in underground camp that borrows heavily from the overly dramatized narratives of Hollywood B movies—these two figures nonetheless share a core belief about filmmaking. Both Kubelka and Smith approach their work with the conviction that film has the ability to take the small and insignificant and make it pregnant with meaning. And this certainty, too, lies at the heart of Friedman’s practice. As she has stated, film allows for “emotional depth and grandeur in a nose, a walk, a posture . . . whatever.” In film, “mistakes become poetry” (1).

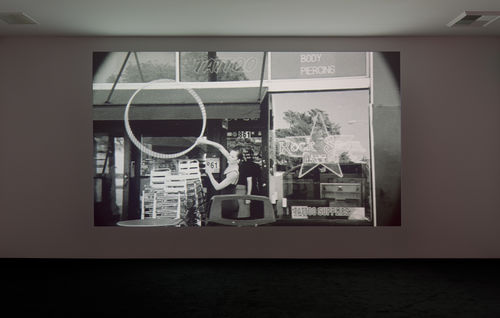

In recent years Friedman’s process has shifted. Rather than locating her subjects in her immediate surrounds (she has described this as akin to bird-watching), she now conceives of an action or behavior and then seeks out trained performers with whom she can collaborate. Her video Musical (2007) grew out of a series of live performances on the streets of Manhattan on one hundred different occasions over a three-week period in which performers would break into full-throated song in public spaces. Upending the expected protocols between performer and audience, Musical made explicit the way the urban environment can be a platform for surprising yet enchanting encounters with strangers. For Dancer (2011), the focus of her exhibition at the Hammer Museum, Friedman enlisted sixty dancers in Miami and shot them performing in diverse outdoor locations around the city, from the rooftop of a museum to Washington Avenue in Miami Beach, from the sandy coastline to freeway underpasses lined with chain-link fences. Some scenes take place in relatively uninhabited industrial zones or in the isolation of the seashore. But many are acted out on the sidewalks of busy commercial districts, the storefronts and building facades acting as a backdrop (at times Friedman, holding her camera, can be seen reflected in the glass windows), and as in Musical, the audience members are made up of random passersby, many of whom stop to observe, their demeanors inevitably affected by the energetic activity suddenly in plain view.

Shot in black and white on Super 16 film and transferred video, Dancer is made up of short vignettes and features a remarkable array of dance and movement forms—ballet and modern, hip-hop and break dancing, tap and tango, capoeira and yoga (and some that defy categorization). The dancers are young and old, coupled and solo, of all colors and stripes, and while some appear to have more training than others, they all share one striking feature—they seem amazingly comfortable in their skins, doing the thing they love and giving it every ounce of energy they can muster. Friedman’s subjects are both confident and vulnerable, consumed by their desire to create something through movement. What we witness as viewers is the beautiful moment when thinking and planning—the choreography—are no longer necessary and the body moves as an unconscious, and perfectly tuned in, extension of the mind. And while their skills are patently evident, they also seem quite ordinary, and by that I mean human. When asked about this quality in her subjects, Friedman notes that what she is seeking to reveal is how perfect and how flawed we all are—in her words, “perfectly flawed.” She takes the stuff of everyday experience—walking down the street, watching dogs play, humming a tune in your head—and amplifies it. Treating the ordinary as extraordinary, she sees pleasure in the mundane and the capacity for the most fleeting of moments to become transformational. Friedman’s work is about life, and to experience Dancer is to feel incredibly alive.

Notes

1. All quotations from Dara Friedman are from e-mail correspondence with the author, November 30, 2012.

Hammer Projects is a series of exhibitions focusing primarily on the work of emerging artists.

Hammer Projects is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Maurice Marciano and Paul Marciano; and Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy.

Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Decade Fund; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.