Hammer Projects: Lucy Raven

- – This is a past exhibition

Lucy Raven uses animation as the foundation for her explorations into the relationship of still photography to the moving image. During her 2011 Hammer Residency, Raven embarked on an ongoing investigation of the invention, growth, and mainstream acceptance of 3D cinema, from its roots in early animation to the current global infrastructure that has been established to support its new-found popularity. In the process, she began to amass an exhaustive archive of film and sound test patterns. Key to achieving high-quality image and sound, these test patterns are usually seen only by projectionists. Raven’s new works press these esoteric image and sound fragments into use as both raw material and subject-matter unto itself, freighted with the patina of analog cinema in a digital age. Hammer Projects: Lucy Raven will feature three new works that promise to broaden our view of the perceptual potential and depth of meaning to be found in the technologies of photography and moving images.

The exhibition is organized by Hammer assistant curator Corrina Peipon.

Biography

Lucy Raven was born in Tucson, Arizona in 1977 and lives in New York City and Oakland, California. Her work has been included in exhibitions and screenings internationally including the Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2012); 11 Rooms, Manchester International Festival, Manchester, United Kingdom (2011); Documentary Fortnight, Museum of Modern Art, New York (2010); Greater New York, PS1, Long Island City, New York (2010); Sound Design For Future Films, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio (2010); China Town and Archive, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, Nevada (2010); Eastern Standard, MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts (2008); In Practice, Sculpture Center, Long Island City, NY (2007); and Con Air II, Performa Radio, Performa05, New York, NY (2005). Raven is a contributing editor to BOMB magazine, and her writing has appeared in publications such as Rachel Harrison: Museum With Walls (Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College/Whitechapel Gallery/Portikus, 2010); Deborah Stratman: Tactical Uses of a Belief in the Unseen, (Gahlberg Gallery, 2010); and Inge Morath: The Road to Reno (Steidl, 2006). She was the co-curator with Fionn Meade of Nachleben at the Goethe Institute, New York (2010); co-curator with Regine Basha and Rebecca Gates of The Marfa Sessions at Ballroom Marfa, Marfa, Texas (2008); associate producer on Urbanized (2012); and co-producer of a series of online documentaries for the Oakland Museum of California (2012).

Essay

By Corrina Peipon

In 2009 Lucy Raven completed China Town, an hour-long video examining the global economy through the lens of copper mining. The video traces the path of copper ore from a mine in the Nevada desert through its processing and refinement at a smelter in China for the production of wire and pipe destined for myriad development projects throughout the country. Following works that consider sociopolitical issues like sustainable energy production, planned communities, public access to information distribution, and the role of labor in civic and commercial endeavors, China Town looks at the environmental and economic impact of an increasingly global need for natural resources.

While these earlier works included traditional hand-drawn animations, China Town is a photographic animation consisting of thousands of still images and a sound track of field recordings made on-site. Relentlessly following leads and asking detailed questions, Raven engaged a process akin to investigative journalism or ethnographic research, gaining a firsthand account of a phenomenon that was previously invisible to outsiders. While she used the tools of reportage, however, the result is something else entirely. Somewhere between animation and documentary, feature and art movie, China Town defies categorization, enacting a kind of resistance that is broached in all Raven’s work.

China Town also explores the roles of photography and film in our collective vision of the world. The inevitably jumpy movement of images and the disjunctive sound track force us to question what we are looking at. A similar critical position in relation to the delivery and reception of images can be found in the structural films of the 1960s and 1970s. The overarching project of filmmakers such as Hollis Frampton, Peter Kubelka, and Michael Snow was to help us understand the elements of film and the construction of meaning. Their analysis of conventional narrative cinema pointed to the vulnerability of audiences to the manipulations of a filmmaker.

Whereas the structural films are about film, Raven’s films are also about how we see and the resources and infrastructure required to make us see in a particular way. In this sense, her project can be aligned with the works of Morgan Fisher, who in Standard Gauge (1984) and other films investigated the territory between commercial and art cinema. Using strategies akin to those of structural film, Fisher lay bare the rarely seen aspects of moviemaking, often including leader, outtakes, and images of the technical ephemera of film. Standard Gauge is literally a film of film: working in 16mm, Fisher filmed a collection of strips of 35mm film, pulling them through the field of the fixed camera’s eye. Rather than focusing entirely on the materials and techniques of film, he explored the historical origin of 35mm as the “standard gauge” of the movie industry and grappled with the differences and similarities—both blatant and subtle—between Hollywood movies and art films.

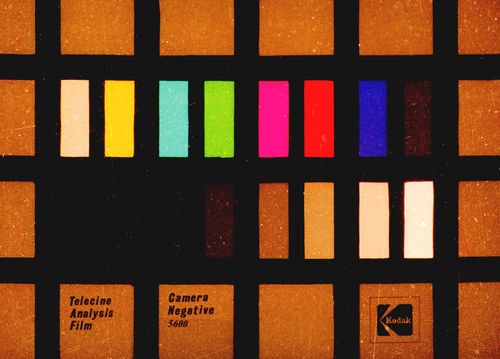

Like Fisher, Raven presses images into labor while also revealing the labor of making images. In her newest work, she investigates the history of film test patterns, which, as she stated in a recent illustrated lecture, “are images you’re not supposed to see, made to make you see better.”[1] Often containing geometric patterns combined with numbers and color spectra or gray-tone gradients, film test patterns help projectionists with the minute details of focus, perspective, and framing, which are essential to picture quality. They have no use beyond projector calibration and possess no meaning beyond their function.

Not considered valuable as films in their own right, test pattern loops have never been formally archived by film historians, museums, or other research institutions. As Raven has noted: “The patterns . . . generally aren’t archived at all. They seem to have been saved almost by accident, or collected in private by particular projectionists. They were often thrown away after the machine they were used to calibrate becomes obsolete. In a way, they survive as an incomplete technological history of film projection.”[2] In her effort to uncover as many test patterns as she can find, Raven may now be their sole archivist.

Collectively titled RPx and xHz, Raven’s new series of film, video, and sound works use test patterns to explore our perpetually evolving aesthetic standards. By using images and sounds that claim objectivity, she is able to call out and question the construction of aesthetics. In RP47 (2012), forty-seven different test patterns appear in segments keyed to a sound track consisting of optically printed sound tests that Raven has been collecting alongside the film test patterns. The sequencing is infinitely randomized by a specially designed computer program. Orchestral passages, piano trills, and industrial blasts are combined into a very “out” experimental composition that is a striking accompaniment to the oddly captivating images. The work is somehow both engrossing and unsettling. As with China Town, RP47’s overriding effect is produced by the perceptible though unarticulated gap between what we see and what we hear, but the format of RP47, with its random sequencing, is decidedly nonnarrative.

Although their aesthetic qualities are incidental, the test patterns are strangely beautiful and formally sophisticated. Reducing the medium of film to its elemental components, the test patterns are like textbook examples of the tenets of modernism. Like all formalist compositions, their insistence on self-reference yields an interrogation of the viewer. Although their aesthetic qualities are incidental, the test patterns are strangely beautiful and formally sophisticated. Despite their clinical appearance and their regularity and purposiveness, their esoteric numerals make them seem mystical or magical. With their radiating diamond shapes, squares, triangles, and concentric circles, some bear a resemblance to mandala designs, possessing a psychedelic or even hypnotic quality. Of course, their mystery derives not from anything metaphysical but simply from an arcane world of pictorial encryption particular to projection booths. Regardless, the test patterns achieve a type of abstraction, however unintentionally, that offers up a host of associations.

For RP31, Raven extracted thirty-one single frames from their loops to create an animated sequence of test patterns. Since the test patterns are specific to the projectors that they were made to calibrate, they include 8mm, 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm gauges with varying film characteristics. Raven digitized the materials, thereby participating in the very process of standardization that her works analyze. After establishing an image sequence, she had the frames printed to 35mm film. By using the “standard gauge,” she underscores the layers of uniformity imposed upon mainstream-media imagery. Each frame of RP31 is on screen for only a fraction of a second, creating an intense strobe effect of colors, lines, and shapes. As a work of abstract animation, the film is connected to historical nonobjective animations, such as the visual music works of Oskar Fischinger and Walter Ruttmann, but its alignment with the materials, techniques, and theories of cinema as a broader category again recalls early structural film. Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1965), for instance, eschewed imagery entirely, reducing the cinematic experience to alternating white and black frames. The only narrative to speak of exists outside the film itself, in its physical and psychological effects on viewers. Like RP31, The Flicker illustrates the artist and film theorist Peter Gidal’s definition of structural films as being “at once object and procedure.”[3]

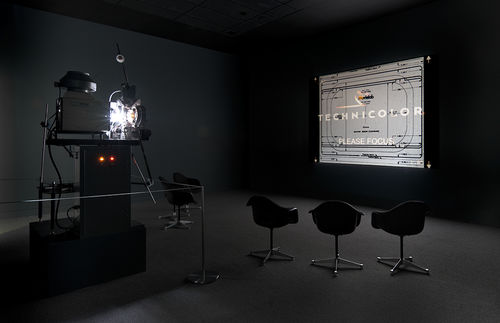

In Raven’s new works, the test patterns are no longer merely functional and subservient to the feature film but are now the focus of attention. RP31 takes this shift one step further. By including the projector and looper in the same space with the projection, Raven highlights the apparatus for which the test patterns are made. Large and noisy, the 35mm projector stands in stark contrast to compact, quiet digital projectors. Its physical presence calls attention to its near obsolescence. In 29Hz, in contrast, Raven gives us untethered audio.

Completely decontextualized, the audio tests encourage both flights of fancy and earnest rumination. Randomly sequenced and infinitely varied, the unceasing “music” is strangely haunting. Raven’s exploration of the materials of cinema in transition engages questions about how we perceive and how media constructs our perception. When the recommended practices for projecting analog and digital cinema are followed, movies look and sound the same across theaters. In this sense, these test loops are deeply influential, dictating a particular aesthetic that we as audiences come to accept as our image of the world.

Notes

1. Lucy Raven “Standard Evaluation Material,” lecture, Artists Space: Books and Talks, New York, April 27, 2012.

2. Fionn Meade, “Anamorphic Materialism” (interview with Lucy Raven), Mousse, no. 31 (November 2011): 142.

Hammer Projects: Lucy Raven is presented through a residency at the Hammer Museum.

The Hammer Museum’s Artist Residency Program was initiated with funding from the Nimoy Foundation and is supported through a significant grant from The James Irvine Foundation.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a major gift from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Decade Fund; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.