Hammer Projects: Antony

- – This is a past exhibition

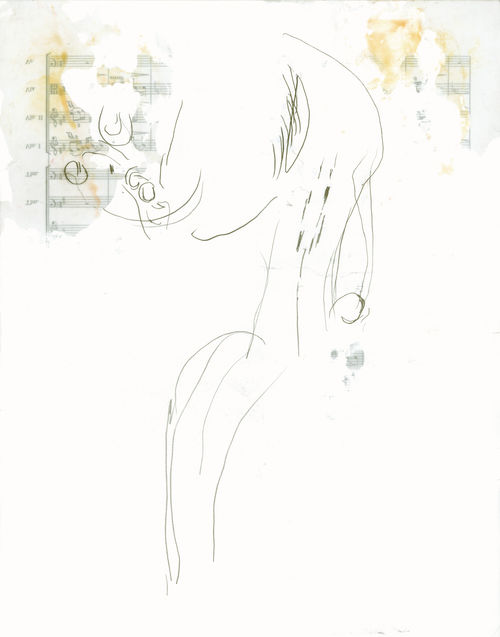

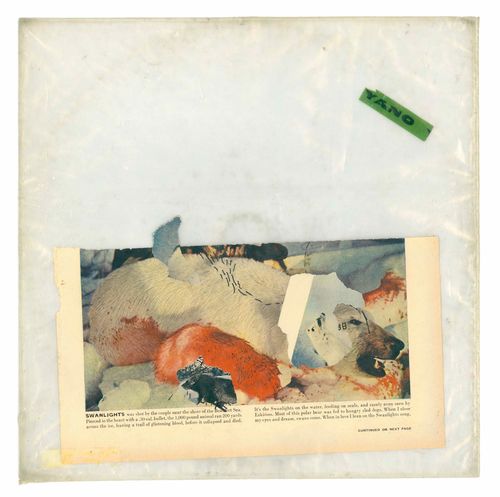

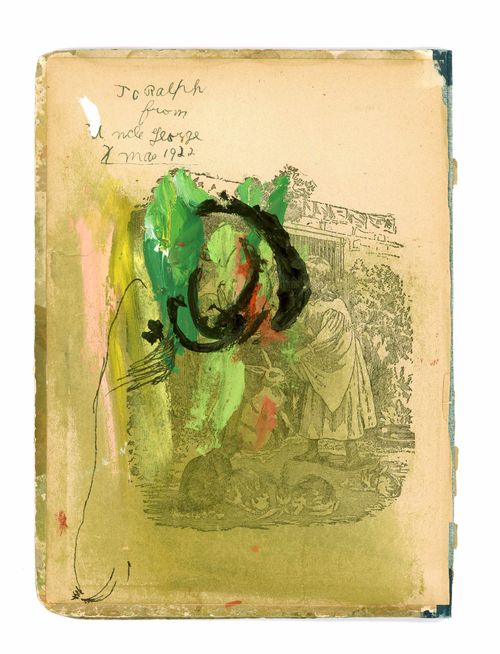

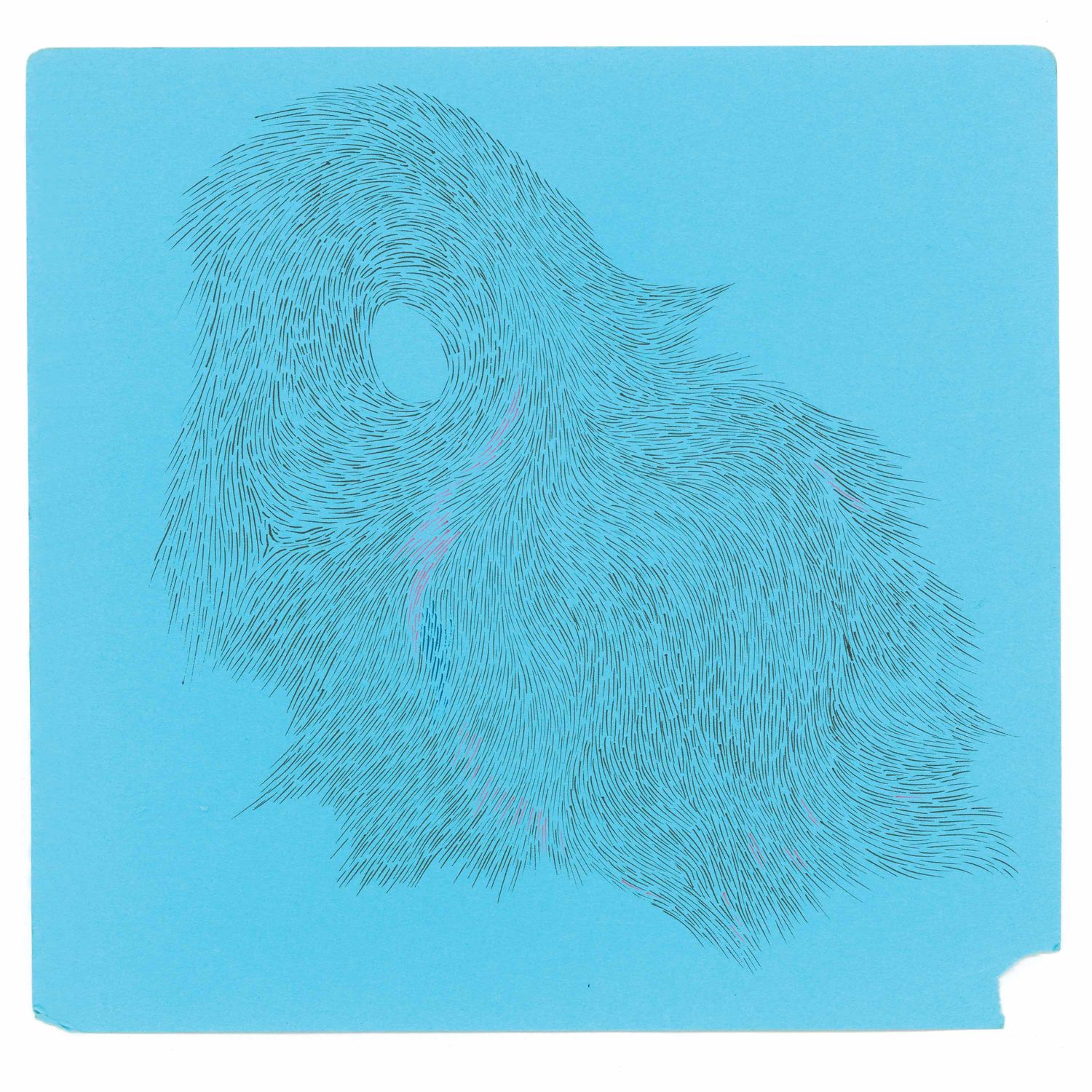

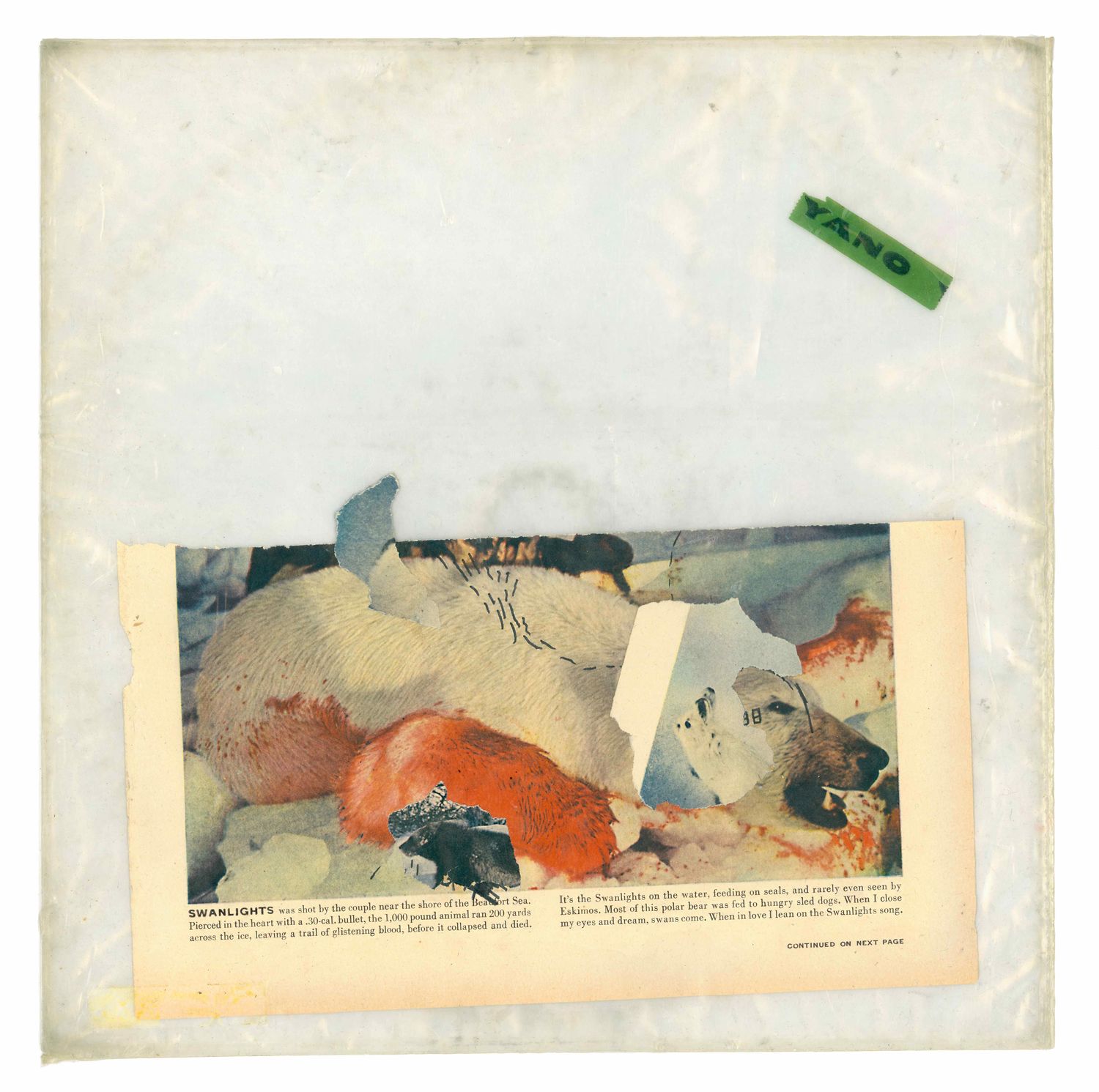

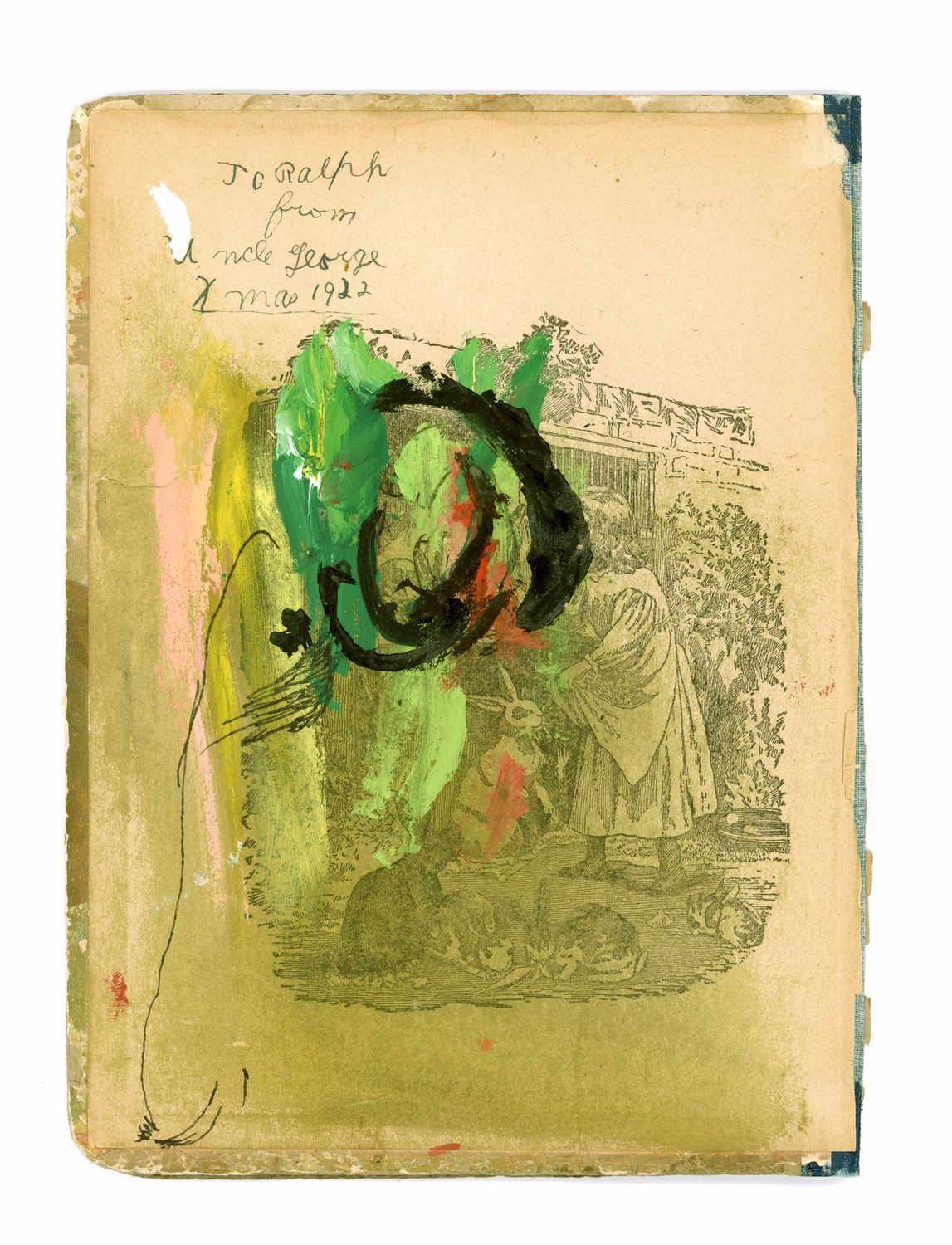

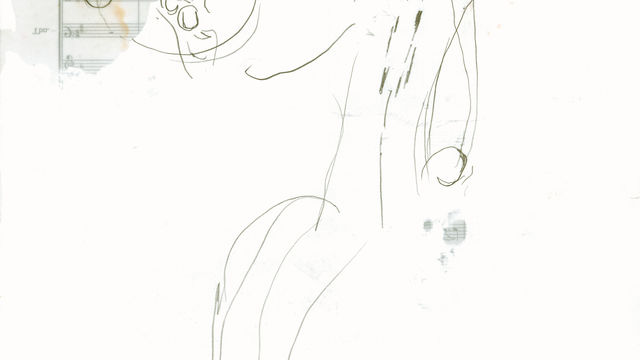

Over the past 20 years, Antony has developed an esoteric and diverse body of work that includes not only his critically acclaimed music and elaborate performances but also his lesser-known work in collage, drawing, and sculpture. Antony’s work emerges from a set of rituals such as washing and burning paper or engaging in repetitive mark-making as well as cutting, tearing, and sewing found images. Antony’s growing visual vocabulary reflects his ideas about the power of human intuition, the sacredness of nature, transgenderism, and the revolutionary potential of the feminine. The exhibition will feature collages and drawings made from the late 1990s to 2011, some of which were recently published in Swanlights, a book accompanying the 2010 Antony and the Johnsons album.

Organized by guest curator James Elaine.

Biography

Born in Chichester, West Sussex, England in 1971, Antony currently lives in New York. Since 2000, he has released four studio albums with his band Antony and the Johnsons. A special edition of the band’s 2010 album Swanlights was accompanied by a book published by Abrams Image featuring drawings and collages by Antony as well as photographs by Don Felix Cervantes in collaboration with Antony. In 2009, a one-person exhibition of Antony’s work was presented at Isis Gallery, London, and he curated 6 Eyes at galerie du jour, Paris. His work was included in It’s not only Rock’n’Roll, Baby! at the Triennale Bovisa, Milan and Palais des Beaux-Art, Brussels in 2010. Antony’s performance projects include Miracle Now (1996); TURNING (2004/2006), in collaboration with Charles Atals; and The Crying Light (2009). Antony was musical director of The Life and Death of Marina Abramović (2011) in collaboration with Abramović and Robert Wilson. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, his performance Swanlights will debut at Radio City Music Hall in 2012.

Essay

Antony: One time [the artist] Kiki Smith said to me, “If you do it with enough conviction, anything can be a drawing.”

James Elaine: I think she’s got a point. When you do something with enough conviction and dedication, it becomes real.

A: You just have to believe in it. I’ve started drawing with burning matches. I only draw when the fire is going.

JE: Your visual expression connects so naturally with your intuition and emotions.

A: I assemble some scraps or fragments, or make some marks. I look for intuitive relationships between things. I have been enjoying that process. The lines I draw tend to seem quite naive. I try to suspend my will and let the line cry in its own direction.

JE: Observing, collecting, and assembling are important parts of your process.

A: It feels connected to nature. I like to get lost in a reverie. I have become convinced that this place is paradise. Even in ruins, even in all its virulence, you can’t deny the shadows of beauty emerging from things. So many people are convinced that a paradise awaits them in death, but I dream of embracing the manifest world as it unfurls around me.

JE: How does making your work, enacting the observation it requires, help you connect to the paradise you describe?

A: By making drawings, I am dreaming. I am trying to listen carefully. I am following something that I imagine is invisible. It helps me connect to an emotional flow of creativity that I value. There is often a sense of mourning in my drawings. For me, hope relies on a shift towards a feminine paradigm. Let’s make a brave gesture. The ecology of our planet is changing very quickly now. We are munching through this place like a plague of locusts. Stephen Hawking said that our destiny lies in the colonization of other planets, but I imagine that this earth and its biodiversity might be the true frontier of creation’s dream. Meanwhile, we’ve convinced ourselves that we’re just here to work out some kinks in our karma before we pop off to some paradise elsewhere. It’s as if we have convinced ourselves that we aren’t mammals, made of water and carbon and minerals. It’s a desperate situation.

JE: To be able to look at the horrors in the world and still press on, to still make things, this is a hopeful and redemptive gesture.

A: For me, to make work is to hope. I want to participate. I’ve asked taxi drivers in New York what’s going on, and they all think that the world is about to end. The scientists are running around trying to gather samples of the world’s seeds and DNA before those things become extinct. Everyone knows the weather is veering off course. The glaciers and the permafrost are melting. And yet, people can more easily accept environmental collapse than they can visualize a shift towards feminine systems of governance. Remember when global warming was just a whisper? It felt like when AIDS emerged in the early eighties. No one was talking about it, but it was happening. We could feel it on our skin.

JE: I think your work is about imperfection, humility, and the knowledge that life consists of constant yearning, loving, and trying. There’s so much room in your work for chance and greater understanding through process. How did you make this drawing?

A: I found the page in an old magazine. I washed it in the ocean and I cooked it over a fire. Then, I washed it again in the ocean. I dried it, and it was all crumbled up, and I started to draw on it.

JE: It’s as though you destroyed it and then brought it back to life. There isn’t much of a line between your art and your life. Your materials come from nature or are the things that arise during the course of your life.

A: I do tend to use found materials. I like the idea that everything today is made from materials which might have been in existence in one form or another for millions of years—the water, the carbon, the minerals. We think of a fresh glass of water as brand new, even though it’s been part of countless life forms before us. Using found materials, for me, emphasizes that the material is already full of life.

JE: Your work is vulnerable, and the found materials you use are vulnerable. You push your materials to the limit, some beyond limits.

A: But, if I go too far, it can be ruined.

JE: Do you differentiate between your art and your music, or are the processes similar for you?

A: The processes are similar because they are intuitive, relatively unstructured, and accumulative. I didn’t study piano or painting. I spent years pouring over the same few chords. When performing a concert, one strives to be very engaged with the people before you, but I tend to retreat when I draw. It’s more solitary; it’s not performative at all. Although later, I will look through things and consider if there is something that I would like to share with others. Often, one drawing will emerge from the process of making another. The Cut Away the Bad series is very specific. All of those pieces originated from the same idea of removing a “bad” part of a found image, often a destructive human presence, in an attempt to restore dignity to the rest of the landscape.

JE: It seems like your ideas gestate deep down inside you until they effervesce to the surface to manifest in your work.

A: The way I make work is often like growing hair or fingernails—it’s a byproduct of living my life. Other times, things come in fits and bursts. Sometimes I’ll burn or wash things and then sort out the remains. Or, I might make a gesture that is very emotional or visceral. Sometimes there will be 20 iterations of a work, and finally one that strikes me will appear; I had to make a lot of them to get there. On the other hand, I might just stare at one drawing pinned to the wall, hurting and hurting at the picture until I understand how to move forward. It’s about aching and sobbing over this piece of paper, trying to find its form. I think that’s a good dream about what creation may be doing: slowly aching, searching for her more perfect form. She’s restless. Is she evolving towards greater gentleness? In a child-like way, I can do that too with a piece of paper. I can have a conversation with spirit.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a major gift from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Decade Fund; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.