Hammer Projects: Alex Hubbard

- – This is a past exhibition

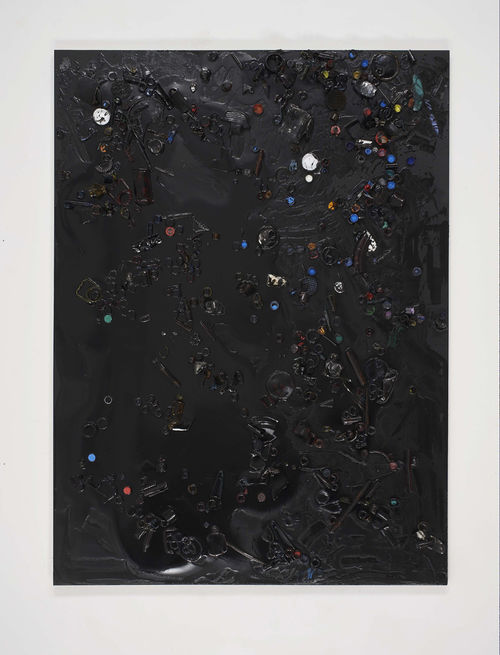

Construction and art materials, urban detritus, domestic items, and even the occasional animal make their way into New York-based artist Alex Hubbard’s dynamic videos. Avoiding a single point of focus, he constructs his videos in layers, creating all-over compositions in which movement is multi-directional and time seems non-linear. Also a painter, his videos and paintings are constructed through parallel strategies, both exploring the construction, composition, mass, color, and depth of images in unexpected ways. Hubbard’s elaborate Foley soundtracks add a delightful and provocative dimension to his adventurous visual narratives that challenge notions of duration and question the difference between looking and watching. Hammer Projects: Alex Hubbard will mark the debut of his newest video, Eat Your Friends (2011). Presented alongside The Border, The Ship (2010), the exhibition will highlight Hubbard’s increasingly complex videos that engulf viewers with bold colors, performative gestures, and evolving compositions. Organized by Hammer curatorial associate Corrina Peipon, Hammer Projects: Alex Hubbard is his first one-person museum exhibition.

Biography

Alex Hubbard was born in 1975 in Toledo, Oregon, and lives in New York. He received his BFA from the Pacific Northwest College of Art and participated in the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. One-person exhibitions of his work have been presented at venues such as Gaga Contemporary, Mexico City; Standard (Oslo), Oslo; and the Kitchen, Maccarone Gallery, and Team Gallery in New York. A two-person exhibition with Oscar Tuazon was presented at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis in 2008. Hubbard’s work has been featured in numerous group exhibitions, including Compulsive Jalouse, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2006); Nothingness and Being, Jumex Collection, Mexico City (2009); The Reach of Realism, Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami (2009); Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2010); Greater New York, MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York (2010); Knight's Move, SculptureCenter, Long Island City, New York (2010), and Le Printemps de Septembre, Festival of Contemporary Arts, Toulouse (2011).

Essay

By Corrina Peipon

Estragon: I can't go on like this.

Vladimir: That's what you think.

—Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot

Airing from 1968 to 1973, Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In featured a style of comedy that ranged from silly to sardonic. The variety show’s title was a riff on words like love-in and sit-in, hallmarks of the hippie and activist countercultural movements of the time. Laugh-In was as goofy as it was stylish and sophisticated. Each episode closed with a live-to-tape segment in which hosts Dan Rowan and Dick Martin traded jokes with cast members in front of their “joke wall,” a cyclorama decorated in a vaguely psychedelic pattern of bright pink, yellow, and green organic shapes that opened like cabinet doors. Assembled behind the wall, cast members—including Ruth Buzzi, Henry Gibson, Goldie Hawn, Arte Johnson, and Lily Tomlin—opened the doors on cue to exchange jokes with Rowan and Martin, often breaking character and clearly wandering off script, flubbed lines leading to improvised hilarity. Verbal and visual non sequiturs were televisual juxtapositions that signified ambivalence with regard to the show’s own position and appropriateness during a time of war and social upheaval.

Another fixture of Laugh-In was the slapstick harassment of original cast member Judy Carne. Her slight frame, pixie haircut, and naive enthusiasm were the perfect foil for such high jinks. In many episodes the pretty English girl in a minidress was doused with a bucket of water after shouting, “Sock it to me!” Oftentimes the water was tossed by someone off camera. The physical, deadpan humor that makes slapstick effective as a comedic device that can both offset and underscore ambivalence is deployed to great effect in New York–based artist Alex Hubbard’s videos. In works like Collapse of the Expanding Field I–III (2007) or Lost Loose Ends (2008), Hubbard uses a fixed point of view—a single camera positioned above a table—to document a series of actions in one take. A cymbal is repeatedly sliced with a circular saw, buds are hastily lopped off a bouquet of flowers, a gift-wrapped box oozes with paint after being crushed by a heavy plate of glass, a cane drags various flotsam across the picture plane. In other works the fixed camera is positioned at a right angle to the floor. Objects enter and exit the frame from all directions and balance precariously on edge, get smashed to pieces, or are covered in paint or wax. As with the anonymous perpetrator of the Carne drenchings on Laugh-In, Hubbard’s hands, arms, and head occasionally appear in the frame as he introduces, manipulates, and removes objects and materials. The result is more akin to animation than to live-action film or performance documentation. Hubbard uses rapid jump cuts and elaborate Foley sound effects that do not always coincide with what we see. The Three Stooges–like effect of the hyperbolic sound design adds a humorous and provocative dimension to these cartoonlike visual experiments.

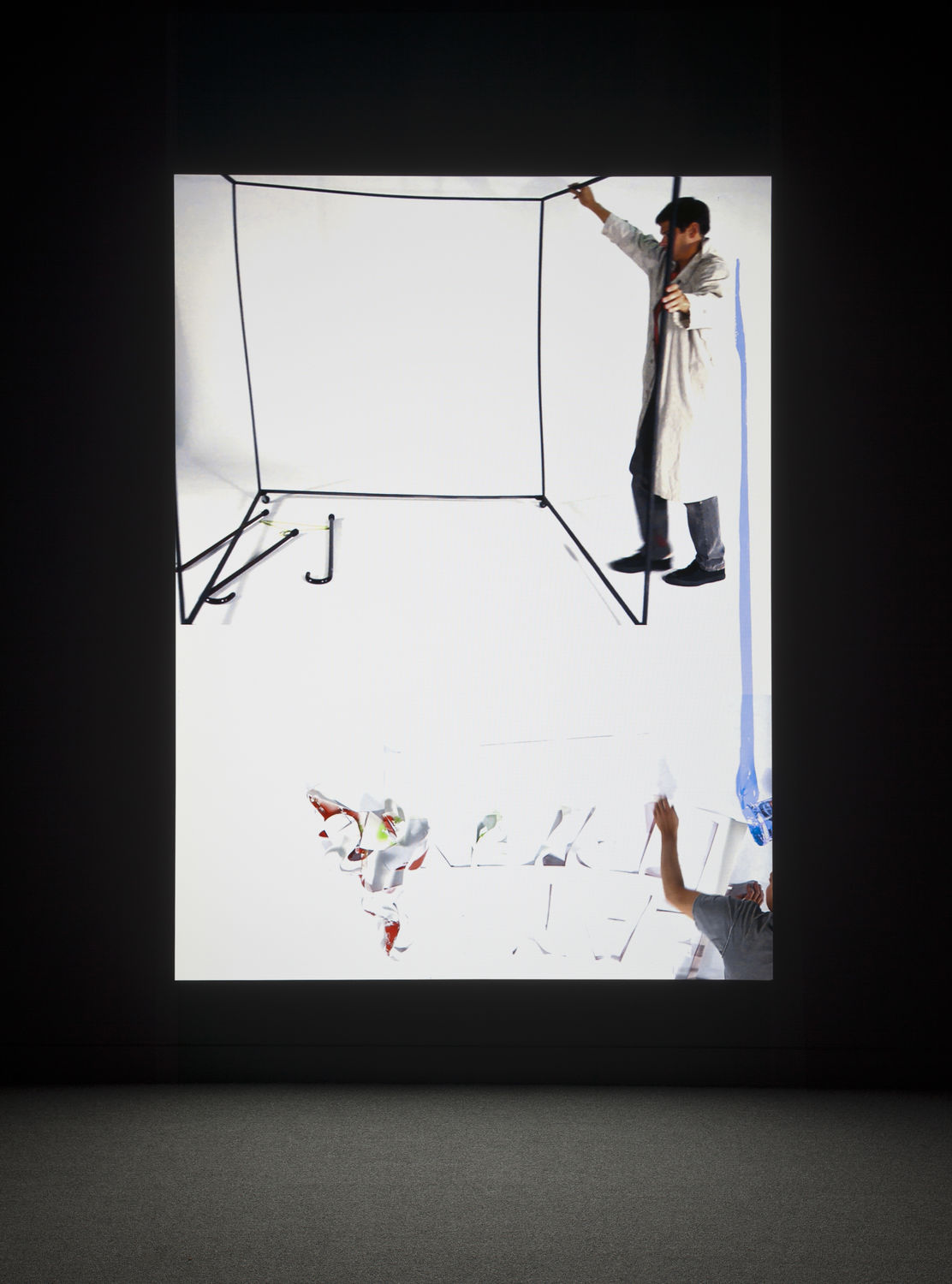

To make his new videos The Border, The Ship (2011) and Eat Your Friends (2012), Hubbard used a white cyclorama. Reminiscent of the “joke wall” on Laugh-In or the green screens used for digital montage, the seamless backdrop provides the illusion of limitless abstract space and invites a wider view of Hubbard and his props. More than in his earlier works, in which the shots are closely cropped but the settings and camera orientation are evident, these videos are placeless. Notably, this lack of identifiable context has allowed Hubbard to exchange a single point of focus and linear series of actions for layered, allover compositions in which multiple actions occur simultaneously, movement is multidirectional, and time is nonlinear. A pipe spouts black paint; an exercise weight tied to a rope moves up and down on a pulley; bones fall from left to right onto a red cloth and are then lowered with ropes from right to left into a bucket of blue paint; a chainsaw gnaws through the crossbeam of a sawhorse and falls upward; an homage to Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column (1938) constructed of bodega takeout coffee cups tumbles into an inky mess; words are stenciled in acid green spray paint. Gravity is defied and depth is revealed where it was not at first apparent: things fall across rather than down, liquid stays put in a bucket tilted sideways, objects and bodies recede into nonspaces. Whereas his earlier works followed a conventional narrative structure, Hubbard eschews linear composition in these new videos. By layering multiple events occurring simultaneously in various parts of the frame, he pulls our attention all around the image. Although objects and bodies traverse the center, nothing remains there. It is in other regions—adjacent to the center, along the borders—that things are really happening.

The timing of Hubbard’s gestures is just as varied as their type, but no matter how quickly or slowly events unfold, movement is relentless. Ranging from cautious or tentative to bold and decisive, the character and pacing of Hubbard’s movements work in concert with our understanding of physical forces to elicit a reaction. We watch with anticipation as objects are piled atop one another until something inevitably falls, gives way, or erupts, resulting in a singular mark or image in a portion of the frame. We experience surprise when a cane entering from outside the frame smashes a vase. Suspense builds as we witness Hubbard’s unorthodox use of various power tools with a willful disregard for safety precautions. In tandem with his physical humor and comedic timing, the confluence of the delight of surprise and the expectation of disaster creates a generative tension, which is the element upon which these works pivot. Rather than being spectacular, the events that occur in these videos are somewhat anticlimactic. One thing does lead to another, but both purpose and causality are constantly disrupted. Nothing really happens in Hubbard’s videos, and therein lie their charm and power. They are rife with the futility that characterizes the absurd.

Founded in 1968 by Richard Foreman, the Ontological-Hysteric Theater is a legendary mainstay of avant-garde theater, staging original works written by Foreman “with the aim of stripping the theater bare of everything but the singular and essential impulse to stage the static tension of interpersonal relations in space.”1 Foreman’s productions are infamous for using antinarrative dialogue, tableau stage blocking, a surfeit of visual information, and a barrage of sonic elements to explore the formal aspects of theater while engaging big philosophical questions. Indebted to historical endeavors in experimental theater—including Bertolt Brecht’s passionate documentary style, Antonin Artaud’s cathartic Theater of Cruelty, and the existentialist theater of the absurd of writers such as Samuel Beckett—Foreman strives to create what he calls “total theater.” Believing that the purpose of theater is to disorient audiences into awakening to reality, Foreman rejects the traditional dramatic structure of setup, conflict, and resolution. The irony inherent in the idea that something as contrived as theater could put audiences more in touch with reality signals a radical ambivalence that drives this style of performance. Like Foreman, Hubbard skips straight to conflict and rarely lets go, thereby creating attenuated tension. Avoidance of fanfare, unceasing movement, and an overarching deadpan approach serve to stave off resolution or release. Both artists search for meaning in the impulse to make images, engaging antiheroic absurdity as a philosophical position.

Hubbard is also a painter, and his videos and paintings are composed using parallel strategies, exploring the construction and reception of images in unexpected ways. Employing fast-drying, fugitive materials such as epoxy, latex, and fiberglass, he is required to move quickly and to accept accidents, improvising gestures in response to the behavior of his materials. In his videos the introduction of each new object into the frame and its subsequent manipulation are akin to the addition of a brushstroke to a painting. Hubbard states: “A moving painting has never been a specific goal but it is something that people often use as shorthand to describe the movies. Maybe the simplicity of the structure relates to painting. A painter may start out with an idea, but the painting will take over and have drives of its own. In a similar way, the videos have their own demands.”2 Though he may begin from a place of mastery over the work that he is creating, his process breathes agency into it. As ideas take form, Hubbard responds to their manifestation, keeping to the script or improvising as needed but never losing sight of the punch line.

Notes

1. Ontological-Hysteric Theater, “About Us,” http://www.ontological.com/INFO/information.html.

2. Anthony Huberman, “Bringing It to the Table,” Mousse Contemporary Art Magazine, no. 22 (February 2010): 22.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a major gift from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; City of Los Angeles; the Decade Fund; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.