Hammer Projects: Shannon Ebner

- – This is a past exhibition

Los Angeles-based artist Shannon Ebner’s work investigates the correlations between photography and language. Informed by various modes of writing—including poetry, experimental writing, and political speech—Ebner constructs images in the studio and the landscape. She builds letters and phrases out of vernacular materials such as cardboard, wood, and cinder blocks, calling attention to the ways language and imagery are constructed. For her Hammer Project, she will exhibit a portion of an on-going project called “The Electric Comma,” which began as a poem she wrote of the same name about various conditions of the photographic, such as its alleged static nature and its vocation of describing events of the past. The poem, or as Ebner refers to it, “the photographic sentence,” seeks to enliven the image by subjecting it to various challenges that ask the photograph to perform outside its usual function of reporting or depicting events, people, places, and things of our time.

In addition to the presentation at the Hammer, works from “The Electric Comma” are simultaneously on display at LAXART in Culver City and in Venice, Italy as part of the 54th Venice Biennale. Portions of “The Electric Comma” have been made into works that are exhibited in all three locations. At the Hammer, Ebner will present two multi-panel large photographic works in Gallery 6 on the courtyard level, and the project will continue outside the gallery with a new piece made specifically for the light boxes leading to the Billy Wilder Theater. The light box work will spell out the word “asterisk,” an element of language and design that has long been featured in the artist’s work, and the boxes will be on a timed lighting sequence so that particular letters and groupings of letters will continuously flash, suggestive of a signal or mechanism for sending and receiving information. In addition to photographs and a video on view at LAXART, Ebner will present an outdoor sculpture in an empty lot in Culver City. An 8-foot tall plywood ampersand titled ‘and, per se and,’ Ebner considers the form and meaning of the ampersand to signify the continual construction and/or incompleteness of meaning between the various aspects of the project and their diverse locations. The Hammer’s presentation is organized by Anne Ellegood, Hammer senior curator.

LAXART is located at 2640 S. La Cienega. The outdoor sculpture is located at the northwest corner of Washington Boulevard at Centinela Avenue.

Biography

Shannon Ebner was born in Englewood, New Jersey in 1971 and lives and works in Los Angeles. She earned her BA from Bard College in 1993 and her MFA from Yale University in 2000 and she currently teaches at USC’s Roski School of Fine Arts. Solo exhibitions include kaufmann repetto, Milan (2010); Altman Siegel, San Francisco (2010); Wallspace, New York (2009, 2007, 2005); P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City (2007). Selected group exhibitions include The Spectacular of Vernacular, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis (2011); the 6th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Berlin (2010); Saints and Sinners, The Rose Art Museum, Waltham (2009); The 2008 Whitney Biennial, The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2008); Learn to Read, Tate Modern, London (2007); Uncertain States of America: American Art in the 3rd Millennium, Serpentine Gallery, London (2006); The California Biennial, Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach (2006); The Plain of Heaven, Creative Time, New York (2005); and Monuments for the USA, CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco. Ebner is also participating in the 2011 Venice Biennale this summer. This will be Ebner’s first museum solo show on the West Coast.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

One of the striking qualities of Gertrude Stein’s writing is her use of what she called a “prolonged” or “continuous” present. Her habitual use of the present tense, coupled with her propensity for repetition, kept her readers in a state of perpetual contemporaneity. Remaining in the present tense gave her writing a sense of immediacy and directness and, paradoxically, did not result in a condition of stasis but instead kept things moving. An American who spent much of her life in Paris, Stein considered this sense of movement to be a particularly American attribute and one that she associated with her own writing: “I am always trying to tell this thing that a space of time is a natural thing for an American to always have inside them as something in which they are continuously moving. Think of anything, of cowboys, of movies, of detective stories, of anybody who goes anywhere or stays at home and is an American and you will realize that it is something strictly American to conceive a space that is filled with moving, a space of time that is filled always filled with moving.” (1)

Shannon Ebner’s practice, too, is manifestly American in that her work of the past several years addresses what it means to be an American in light of current global political and economic trends. She has both directly and obliquely commented upon the wars in the Middle East, Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, and the border between Mexico and the United States, among other charged topics. As an artist who resides outside the more traditional practices of her medium, like the photographic essay or investigative journalism, Ebner has commented upon feeling a kind of impediment to the movement that these more conventional practices demand. But rather than satisfying her desire for movement physically by traveling and documenting the world, she looks, as Stein did, for movement within form, within the form of the photograph itself.

Ebner’s photography is deeply embedded with language. An abiding concern with the conditions of photography characterizes all her work, and at the center of this investigation has been her exploration of whether a photograph might exist in the continuous present that Stein articulates. Representational photography has a long history of locating time and place, its primary function perceived to be that of capturing a moment in time or revealing an aspect of a place. Abstract photography has resisted this specificity, usually by narrowing its focus to the formal attributes of the medium. Ebner, however, is interested in whether this sense of indeterminacy—what she terms an “anti-place” or an “anti-landscape”—can be expressed through representational photography, that is, through photographs of places and things. Poetry’s ability to be at once incredibly specific and completely open is a model for the artist, who uses language as a starting point for and a subject of her work.

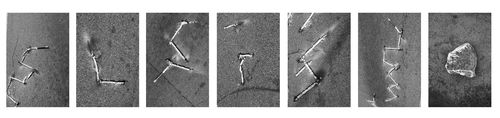

To embark on a new body of work—a portion of which is on view at the Hammer Museum—Ebner began writing a poem titled “The Electric Comma.” Over the past few years, she has become preoccupied with what she calls “the photographic sentence.” Posing the question “When is a photographic sentence a sentence to be photographed?” Ebner approaches language as an object by building the very letters that become the subject/object of her photographs. The modular photographic letters made of cinder blocks (which Ebner refers to as the “STRIKE alphabet” (2)) can then be combined to form words and phrases. She will often replace particular letters with symbols such as asterisks or backslashes, which have the effect of disrupting legibility.

In addition to this studio-based production, Ebner locates marks and traces in the world that suggest language—a black “X” spray-painted on the door of a retired police car or ashes left over from emergency road flares. Whether constructed or found, Ebner’s invocations of language remind us of its arbitrary nature and sometimes tenuous relationship to meaning, how it is both able to signify and open to innumerable interpretations. By translating words into a photographic sentence, she pushes language into the realm of the visual, illuminating the architecture intrinsic to communication, which we oftentimes take for granted. Simultaneously, she proposes that photography can enact something far beyond description, surpassing its position as a static object to become a sort of protagonist in a narrative that is continuously present or, as Ebner terms it, ecstatic.

The notion of the ecstatic comes from the Greek word ekstatikos, meaning “unstable.” The opposite of static, an ecstatic state is one in which a body is no longer at rest and has been put into motion. It is dynamic, potent, and energetic. Ebner’s ecstatic photographs challenge ingrained expectations for the medium to provide documentary facts or “truthful” representations. One way that the artist creates this sense of movement or instability is to create images that are simultaneously familiar and curious. At first glance, the photos appear to feature time-honored subjects—the landscape, a monument, an urban street scene—and indeed Ebner deliberately works with common genres. But these recognizable subjects become distorted, complicated through a layering of references that make them difficult to decipher yet open to newfound possibility. Just as language can sit flatly on the page or become almost invisible as a form when its sole purpose is to pass along information, photography, too, can be limited by an emphasis on content with little regard for its other attributes. Ebner’s desire to upend the stillness of photography is mirrored by her concern with the potential stasis of language. Some of her works directly address the cynical rhetoric of political language, in which particular words or phrases are feverishly lobbed at the public in order to sway opinion or instill fear. The result is that these words begin to teeter on the edge of meaninglessness. This, of course, happens outside of political speech and, indeed, within art historical discourse, wherein certain notions gain so much favor that over time the specificity of meaning begins to fade. By pointing to these “hot” words, as Ed Ruscha has called them,3 she insists that we struggle to locate meaning while also acknowledging that these efforts will inevitably falter, as new meanings within new contexts present themselves.

Exhibiting work concurrently at several different sites, Ebner has pulled particular words or phrases from her poem “The Electric Comma” to create individual works, decontextualizing and unmooring the language so that the source of the poem becomes secondary to the ideas explored in each work. In the gallery at the Hammer are two large-scale multipanel photographic works that zero in on the word electric and the X form. The first is a four-part piece that combines constructed and found language. The title of each image—XSYST, EKS, EKSIZ, XIS—is designed to play on the provocative verb exist as well as on the sound of the letter itself. The same set of four images is also incorporated into a larger piece currently on view at the Fifty-Fourth Venice Biennale, (A.L.N.G.U.E.*.F.X.P.S.R.), which consists of twenty-eight prints that fill a wall, mural-like. The phrase “language of exposures,” which makes up the piece, is drawn directly from Ebner’s poem. The “language” that the artist proposes here is one that marries word and image so that one can substitute for the other, providing an alternative system for conveying meaning. “Exposures” also suggests a certain vulnerability or instability, a way of operating that will, as Ebner has stated, “disarrange the photographic universe.” (4)

After addressing the reader, “The Electric Comma” begins by stating that the twenty-seventh letter of the alphabet is a blank, comma, or delay. Drawing on the work of engineer and mathematician Claude Shannon, who is today considered the “father of information theory,” Ebner is interested in the pauses or delays in language and how they can complicate or redirect a message. Shannon considered the pauses or spaces within language to be as integral to communication as the letters of the alphabet. Similarly, for Ebner, blankness is never truly empty space; she considers it to be akin to a breath or a slight delay, like a comma. It is in the space of this momentary lapse that an exposure can be made or an image can resist delivering its message, causing another form of disruption. At the third venue for the project, LAXART, this twenty-seventh letter of the alphabet is articulated in three separate but connected works that spell out the words comma, pause, and delay. Additionally, Ebner has produced a photovoltaic (solar) sculpture that is on view concurrently in an empty lot in Culver City and on a balcony overlooking the Grand Canal in Venice, Italy—an eight-foot-tall plywood ampersand titled and, per se and. She considers the form of the symbol to signify the continual construction and incompleteness of meaning. All her work makes us aware of language’s inherent limitations and argues for the ways in which it benefits from photography. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein articulated the problem beautifully: “The limits of language is [sic] shown by its being impossible to describe the fact which corresponds to (is a translation of) a sentence, without simply repeating the sentence.” In her study of Wittgenstein, Marjorie Perloff expands on his point, suggesting, “He might have added that poetry is the ‘form of life’ that shows this limitation most startlingly.” (5) Ebner’s work breaks language free of this tautology, providing poetry with a visual correlation that electrifies both language and photography.

Notes

1. Gertrude Stein, “The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans,” in Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein (New York: Vintage, 1990), 258.

2. Ebner’s first use of this alphabet was for a work titled STRIKE, included in the 2008 Whitney Biennial.

3. See Yve-Alain Bois, “Thermometers Should Last Forever,” October, no. 111 (Winter 2005): 60–80.

4. This phrase is from a section of the poem “The Electric Comma”:

NOW GO OUTSIDE THIS TIME & PLUG IN SOME REALLY LONG CHORD

THIS WILL MAKE YOUR PHOTOGRAPHIC DANCE THE ELECTRIC COMMA

AND PROMPTLY DISARRANGE THE PHOTOGRAPHIC UNIVERSE

I STATE THIS COMMA

TURN IT AROUND

TURN IT AROUND

5. Both quotations are from Marjorie Perloff, Wittgenstein’s Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 199.

Shannon Ebner’s Hammer Project is a collaboration with LAXART where the exhibition continues in the gallery and with a concurrent public art project, part of the on-going programmatic partnership between the Hammer and LAXART.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; L A Art House Foundation; Kayne Foundation—Ric & Suzanne Kayne and Jenni, Maggie & Saree; the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.

Hammer Projects: Shannon Ebner has also received support from Stacy and John Rubeli.