Hammer Projects: Sara VanDerBeek

- – This is a past exhibition

For the past several years, Sara VanDerBeek has explored the relationship between photographic imagery and sculptural forms. Working with a large archive of historical and personal images, she builds photographic assemblages in her studio and captures them in singular images. Recently, she has been shooting photos in American cities that carry particular personal, historical, or political meaning for her, including Detroit and Baltimore. Invited by the Hammer to participate in our Artist Residency Program, VanDerBeek spent several weeks in Los Angeles over the past year. The works included in her Hammer Project have grown out this residency and offer a particular view into our city. In the past, VanDerBeek’s sculptures have been built in order to be photographed, and for the first time, she will be presenting sculptures in the gallery alongside her photographs. Additionally, she has designed an installation within which the works will be presented—part stage-set, part studio, part imagined space. Resisting the iconic or spectacular, the works in the exhibition distill VanDerBeek’s experiences of Los Angeles and operate in the boundary between abstraction and representation. While touching upon various locations and attributes that define our city—from the diverse landscape to the region’s indigenous people, from Hollywood to community theater—the sculptures and photographs are primarily concerned with movement, materialty, and mark-making.

Biography

Sara VanDerBeek was born in Baltimore in 1976 and lives in New York City. She received her BFA from Cooper Union School of Art and Science in New York City in 1998. VanDerBeek has had one-person exhibitions at The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2010); Altman Siegel, San Francisco (2010): The Approach, London (2008); and D’Amelio Terras, New York (2006). Her work has been included in numerous group exhibitions, including The Anxiety of Photography, Aspen Arts Museum, Aspen; Knight's Move, SculptureCenter, Long Island City; Image Transfer, Pictures in a Remix Culture, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle; Haunted: Contemporary Photography/Video/Performance at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; New Photography 2009 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Amazement Park: Stan, Sara and Johannes VanDerBeek, The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs; The Reach of Realism, Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami; and The Library of Babel / In and Out of Place, Zabludowicz Collection, London.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood, Hammer senior curator

Anne Ellegood: Can you speak about the relationship between photography and sculpture in your work?

Sara VanDerBeek: I am fascinated by the transformative quality of photography. Photographs can affect your sense of time, place, memory, and scale and thus are attuned to the central aspects of our existence. Photography is also about acute observation, the power of vision, and what can be gained from looking. It can function in many different ways—as a record, as an object, as a form of communication. When we experience something significant and want to capture that moment in an image, are we doing so because it is “historic” or because it has become an innate action, a reflexive processing of events? This type of questioning applies to my knowledge of art history and the history of sculpture in particular. My knowledge and memory of many works of the past are based upon their documentation rather than a primary experience. When viewing the work in person, I often compare it with my recollection of its image. This caused me to consider the ongoing relationship between sculpture and photography. I realized that I could investigate this process from object to image to object in my practice. In my earlier work I began by creating an object and then capturing it as an image. Then, through the process of making a final print, framing it, and hanging it on the wall, it becomes an object again. The color, texture, and scale of the print contribute to its presence as an object. An image has a particular strength and resonance when seen in person. The dynamic nature of sculpture resides in its dimensionality. I don’t think I fully understood this until I started to make the objects for my Hammer Project.

AE: Your work has always had a great deal of historical, cultural, and political content. In recent years you have traveled to a number of cities to shoot photographs. Your interest in Detroit and New Orleans is related to the impact of recent economic and environmental hardships in those cities but also to earlier moments of racial migration and urban development. Can you talk about your interest in these issues and how your work relates to journalistic photography and photography that has a social agenda?

SV: All forms of photography are of interest to me, but I have an affinity for photographers who have social concerns. I admire those who can concisely capture a significant moment in a single image. Images can still be very powerful; their ubiquity and number do not seem to diminish their strength. My interest in exploring different places in America that have been formative to our history and our sense of self comes from a desire to understand our present. For me, one of the ways of furthering this understanding has been through site.

AE: For your Hammer Project, you’ve decided to include sculptures in the gallery alongside your photographs for the first time. In the past, your sculptures always existed as objects in the studio intended to be photographed but never included in the gallery. What brought about this transition to exhibiting sculpture?

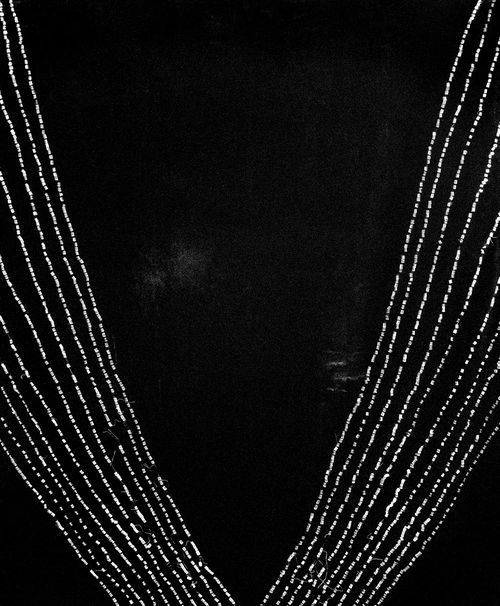

SV: The camera helps me to frame and observe in many different ways—intimately, slowly, but also immediately. I’m hoping that the sculptures in the show have a similar quality of transformation. Control and chance are two elements that I both embrace and fight. I enjoy the control that the camera offers me, but I also wish to be more gestural and am excited when outside influences contribute to the creation of an image or an object. The photographs and the sculptures explore ideas of performance, myth, and memory as well as the presence or absence of the body. Many of the photographs are taken at Western Costume in Burbank: close-up details of the garments worn by background characters, those not often seen in front of the camera. I felt the ghosts of the many performers enmeshed within their fabric. The sculptures relate to human scale. I hope there is a transparency to the experience of the exhibition and a sense of illusion, the suggestion of an imaginary world or theatrical space.

AE: Tell us about your experiences as an artist-in-residence at the Hammer.

SV: If there is a place that feels like the embodiment of a collective dream, I think it is Los Angeles. But it is not all beautiful. The dark and gritty moments, combined with the ever-present sunlight, grant an unreal quality to everything. It is a photogenic city; you understand why people came out here to make movies. It is its own place, but it can also transform easily to feel as though it is somewhere else. Its simultaneous specificity and anonymity are unique. I traversed many areas of the city, including photographing architecture in the Hollywood hills (Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House and the Schindler House in particular), the desert plants in Joshua Tree, Sequoia National Park, various locations in West Adams as well as prop and costume houses. Diverse. Fragmented. Sprawling. L.A. is a city you can get lost in and easily confuse where and when you are. I wrote in my notebook during one of my residency trips, “Everything is dramatic in California.” Most significantly, it is apparent that this is a constructed environment. Los Angeles feels as though it is newly built upon an ancient plane, and to me, that is the real character of the city and what contributes to its dreamlike quality.

AE: You designed an installation for your Hammer Project that functions as a room within a room. Can you tell us about your desire to create this space and how you think it will impact the understanding of the photographs and sculptures on view?

SV: This room within a room is like a camera or photograph: a space that we comprehend but that also falls between the imaginary and the real. I see the installation as a dream room, a parallel space similar in size to my studio on the other side of the country. I enjoy visiting historic homes because they are filled with faint reminders of their occupants. I would like the room I have constructed in the gallery to feel as though it had been activated at some previous time.

AE: Can you discuss some of the works that you made for the show?

SV: What has been both exciting and challenging for me about this experience is that I have opened up my practice. I went into establishments like House of Props and Western Costume. I began to take as my subjects the articles within these spaces, not just the structures, which had been the focus of past projects. Many of the materials for the sculptures, such as steel and plaster, remain connected to architecture, but there are also natural forms and found materials. The sculpture Four Directions (2011) is influenced by totemic forms as well as modernist designs like Frank Lloyd Wright’s textile concrete blocks and the domestic objects of Jean-Michel Frank. The mica on the work’s surface is inspired in part by Frank’s use of the material as well as its use for ancient American artifacts. The long white fringe in the sculpture The Visible (2011) was inspired by costume details. I used theatrical paints and other materials as finishes for the sculptures.

AE: You have mentioned that performance is a central idea explored in the works here. Can you elaborate on this?

SV: In addition to the sense of the room as a theatrical space, I have also been exploring other forms of performativity. I have been attending powwows in the Los Angeles area and learning more about contemporary Native American culture and dance, in particular through my interactions with Sonya Flores and Moontee Sinquah, two remarkable dancers. I have been very inspired by the regalia they wear when dancing and the transformation that occurs within the dancers’ bodies as they move.

AE: How is your investigation into Los Angeles similar to or different from those of the other cities you’ve shot?

SV: This is the first time that I am exhibiting my explorations of a city in the same city. I wanted to create an installation that would be a synthesis of my experience of Los Angeles but that, like previous projects, would also address larger issues. When considering a city, I think about both the individual, intimate view of the place and the larger community, as expressed in the city’s history and evolution. It is both incredibly inspiring and terrifying to realize that we are capable as individuals, and as a collective, of enacting great progress, achieving peace, and advancing humanity, and are therefore equally able to engender their opposites. It rests in all of us, our history and our future.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; L A Art House Foundation; Kayne Foundation—Ric & Suzanne Kayne and Jenni, Maggie & Saree; the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.