Hammer Projects: Linn Meyers

- – This is a past exhibition

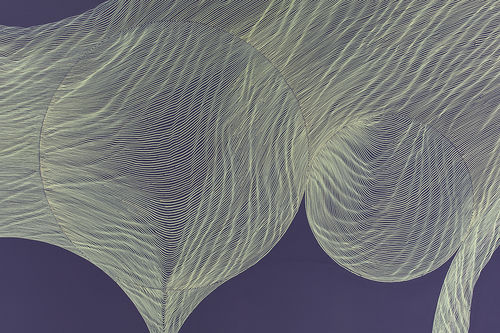

Time is central to the work of Washington DC-based artist Linn Meyers, whose practice revolves around drawing. Each dense and intricate ink line drawing is the result of a nearly meditative process by which Meyers lays down consecutive lines into largely organic forms, creating rhythmic repetitive patterns. Each line becomes the record of a physical movement, and the inevitable inconsistencies and imperfections of the body as it moves through time and space become integral to the final composition. Meyers’s layering of vivid colors creates a shimmering quality suggestive of light and movement across the surface of the work. Working in a range of scales, Meyers has in recent years moved from the page to creating site-specific wall drawings. Ambitious in scale and labor, these drawings can take several weeks to complete, their shapes responding to the architecture of the space and the surrounding elements. For her Hammer Project, Meyers will make a large-scale, site-specific wall drawing on the Hammer’s lobby wall. This exhibition will be the artist’s first museum show in Los Angeles.

Biography

Linn Meyers (b. 1968) currently lives and works in Washington, DC. She earned her BFA at The Cooper Union, New York and MFA from California College of the Arts, San Francisco. Meyers has had solo shows at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, DC; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; The University of Maryland, College Park; G Fine Art, Washington, DC; Margaret Thatcher Projects, New York; Gallery Joe, Philadelphia; and Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg. Meyers has also participated in several group shows internationally including the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tokyo and Paris Concret, Paris. She has received numerous awards including the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, Artist-in-Residence at the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art, Artist-in-Residence at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Artist-in-Residence at the Tamarind Institute, the Trawick Award, Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, Excellence in Drawing Award from The Cooper Union, Artist-in-Residence at the Bronx Council on the Arts, and the Alex Katz Scholarship to Skowhegan.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

Our representations of inspiration are far from perfect for perfection is unobtainable and unattainable. —Agnes Martin (1)

A line is the most elemental and foundational of human marks. Lines become language. They coalesce to form representations. They delineate space. And sketch out ideas. For artist Linn Meyers—for whom the hand-drawn line is a source of endless inspiration and the starting and ending point of each work—the line also marks time.

Drawing’s fundamental relationship to humanity—its integral role in nearly every aspect of our lives—is at the core of Meyers’s practice. She says: “That is why I make drawings and can’t work my way into other areas of art making. I am totally enamored of the simplicity of the line. We are all familiar with the line. We all use it. We all write. It’s built into us.” (2) Trained as a painter, Meyers initially gravitated toward painting magical landscapes that embodied particular emotions. In these early pictures the horizon line was always a prominent feature. As she grew more comfortable with focusing on the feelings that the works evoked rather than the sites themselves, the horizon line disappeared, and the paintings became more atmospheric. Not wanting to divorce herself from landscape altogether, she depicted subjects that could surround the viewer, like the sky. She had let go of pictorialism, but the work was still inherently representational. While she eventually stopped including elements of landscape in her compositions, she resists the idea that her works have become wholly abstract. Nature, the horizon line, atmosphere—all these are still in the work, but now they are simply embodied within the line rather than delineated by it. By distilling her mark making to a simple line and then repeating the lines until they fill a void (however big or small), she creates works that function like a map of sorts, charting time and space.

Meyers’s drawings are very much about being present in the moment. Her gradual paring down and removal of influences and expectations has, perhaps counterintuitively, given the artist an infinite number of possibilities. She builds each drawing by first creating a framework of interconnecting circles across a field of color, which provides both a simple composition for the work and a self-imposed structure. This basic structure is reminiscent of the “rules-based” process at the core of Sol LeWitt’s conceptual drawings, an evident precedent to the systematic nature of Meyers’s work. Yet while LeWitt’s instructions leave little room for organic “slippages” (to use Meyers’s word for slight deviations from the planned pattern), Meyers begins with a structure but allows the inevitable unplanned marks to take the work in unforeseen directions. Another important distinction is that while LeWitt’s work consists of precise instructions that can be acted out by others, the real-time decisions that occur in the more organic unfolding of Meyers’s drawings in time and space require that she make them herself.

Within the matrix of predetermined circles, Meyers lays down consecutive lines of color, creating rhythmic, repetitive patterns. Each line is literally the record of a specific movement of the artist’s body through space. The accumulation of the lines into dense and intricate drawings is the result of a prolonged action, a nearly meditative process steeped in repetition, which requires a great deal of endurance. Having worked on paper for many years (and primarily on semitransparent Mylar paper), Meyers began making site-specific wall drawings a decade ago. This larger scale not only allowed her to respond to an architectural space but also enhanced and magnified the aspects of her work that interested her most—the wholly committed performativity of the process, the resistance to illusion and representation in favor of the directness of materials in space, and the concept of entropy, wherein things become more disorganized over time. The sense of being present while viewing the work is also amplified at this larger scale, allowing viewers to experience the work not just visually but also physically. To see a wall drawing is to be surrounded by it and to feel oneself to be part of the work. Meyers’s layering of vivid colors creates a shimmering quality suggestive of light and movement across the surface of the work. The circular patterns conjure the most fundamental aspects of the universe, both big and small—from a fingerprint to a galaxy, from cellular patterns to tidal waves.

While the systematic structure and the intense attention to formal considerations evident in Meyers’s work bring to mind the quiet and enduring poetry of Agnes Martin and Anne Truitt, as well as LeWitt’s wall drawings, Meyers feels an abiding connection to the paintings of Jackson Pollock. Art historian Rosalind Krauss has described Pollock’s abandonment of the brushstroke in favor of dripping paint directly onto a canvas lying on the floor as a form of mark making that functions like a trace or index. The lines are the remains of something, clues to an event that has already occurred. This approach to mark making distinguished Pollock because, despite his association with abstract expressionism, he was deliberately moving away from what Krauss calls the “autographic” brushstroke. In other words, the work was not intended to be expressive of his interior emotional states despite its arguably energetic and vital appearance. Rather, its allover composition was a blow against the notion of the painting as something whole and complete. Krauss writes, “It strikes against the organic form’s condition as unified whole, its capacity to cohere into the singleness of the good gestalt, its hanging together, its self-evident simplicity.”3 Pollock’s paintings are notably uncontained: they have no center, no focal point; they appear as if they could go on in any direction endlessly. This commitment to a nonhierarchical composition and move away from providing an edge or clearly delineated space for the work are embraced by Meyers. Like Pollock’s paintings, her drawings are the evidence of an action; they are traces or indexes of an event requiring intense stamina and patience. While the outcome may feel decidedly different—Meyers’s work embodying a more regulated and methodical approach—she shares Pollock’s fascination with “baseness,” with the most fundamental of human behaviors. She is after a purity of making—a physical process that does not hide behind illusionism—a directness wherein the materiality of the work is evident and, as she has said of Pollock, “all the mystery is removed so that it is what it is.” (4)

For her Hammer Project, Meyers has created a composition that responds directly to the architecture of the lobby stairwell. Approaching the two adjacent walls as a connected space for one drawing while simultaneously addressing the gap between them, she has created compositions that mirror each other to some degree. The downward slope of the staircase provokes a feeling of tumbling, the circular forms appearing to gradually slide toward the bottom corner. Gathering at the landing and bumping up against the negative space of the gap between the walls, the composition is then picked up and continues on the soaring east wall. In the past, Meyers’s approach to color has been highly intuitive, informed in large part by her formal investigations into the interactions of a relatively contained palette. Each work is generally limited to only two or three colors, with one serving as the background and another for the line work. In selecting the colors for her work at the Hammer—titled Every now. And again.—Meyers has gone in a new direction whereby she extends the notion of site-specificity beyond the architecture of the space to encompass the city itself. Taking note of the colors that characterize Los Angeles, she was drawn to the particular hues of the sky as the sun falls below the horizon. Two shades of a dusky purple—one warm and one cool—provide the background for an elaborate wall drawing in pale yellow ink. Creating the work in a city with a deep connection to the landscape and installing it in a space in which daylight spills through the lobby windows, Meyers recognizes that color is an intrinsic part of the lifestyle here. More than a formal exploration of color, composition, and space, Every now. And again. resonates with our everyday experiences of our surroundings. It captures the light and color of Los Angeles and offers it back to us in a form that is at once direct and contemplative, immediate and suggestive of the passage of time.

Notes

1. Agnes Martin, “Reflections,” in Agnes Martin: Writings, ed. Dieter Schwarz (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 31.

2. Linn Meyers, conversation with the author, March 27, 2011.

3. Rosalind E. Krauss, The Optical Unconscious (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), 266. 4. Meyers, conversation with the author, March 27, 2011.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; L A Art House Foundation; Kayne Foundation—Ric & Suzanne Kayne and Jenni, Maggie & Saree; the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.