Houseguest: Frances Stark Selects from the Grunwald Collection

- – This is a past exhibition

Houseguest is a series of exhibitions at the Hammer Museum in which artists are invited to curate a show of material from the museum’s and UCLA’s diverse collections. For this exhibition, Los Angeles-based artist Frances Stark chose to sift through the works in the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, a collection of more than forty-five thousand prints, drawings, photographs, and artist books dating from the Renaissance to the present. Stark began her research without a specific theme in mind, a process that she describes as “surrendering to taste and to the chance of discovery.” She found herself instinctively drawn to figurative and metaphorical renditions of man and woman. Her exhibition takes the form of a visual essay on the sexes, transporting the viewer through a panoply of themes central to human experience: creation, reproduction, pleasure, the essence of the body, relationships, identity, and death. Stark eliminated photographs from the outset, focusing instead on the intuitive lines of prints and drawings by artists as diverse as the sixteenth-century German printmaker Hans Sebald Beham and contemporary artist Mike Kelley. Each image converses with the next in Stark’s installation, reflecting a flow of moods and sensory transitions from the elated to the melancholic. The exhibition also includes works by Isabel Bishop, Jacques Callot, Edgar Degas, Francisco de Goya, Agnes Martin, Ken Price, and Egon Schiele.

This exhibition is organized by Allegra Pesenti, curator, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts at the Hammer.

Biography

Frances Stark was born in Newport Beach, California in 1967 and lives and works in Los Angeles. She received an MFA from Art Center College of Design, Pasadena in 1993, and currently teaches at the University of Southern California. Her work was shown at the Hammer Museum in 2002 as part of the Hammer Projects series. Other one-person exhibitions have been presented internationally at venues including the Centre for Contemporary Art, Glasgow, Scotland; greengrassi, London; Marc Foxx, Los Angeles; CRG, New York; Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne. Stark’s work has also been featured in thematic exhibitions such as Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900-2000, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2000-2001); Monuments for the USA, White Columns, New York (2005-6); Romantic Conceptualism, Kunstverein, Nuremberg, and BAWAG Foundation, Vienna (2007); Fit to Print: Printed Media in Recent Collage, Gagosian Gallery, New York (2007-8); and Learn to Read, Tate Modern, London (2007). She also participated in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Her solo exhibition Frances Stark: This could become a gimick [sic] or an honest articulation of the workings of the mind opens at MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts, on October 22, 2010, and her work will appear in the exhibition All of this and nothing, which opens at the Hammer Museum on January 30, 2011.

Essay

By Linda Norden

It is often said of Frances Stark—often by Stark herself—that her medium is language. Writing of all sorts—criticism, experimental fiction, expository essays—occupies as much of her attention as image and object making, and literature is as likely a source for her art as imagery or graphic typography. It’s also true that, as often as not, the “imagery” that she composes consists primarily of text, albeit appropriated text, subject to the tampering hand of the artist. But language is a loose term, and Stark’s engagement with literature is more like than different from her engagement with imagery; she is after something interior that provokes her. In a 1997 article on Stark, Dennis Cooper describes seeing a group of jaded high school students touring an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. To his surprise, the students abandoned their “tightlipped nonchalance” and suddenly became animated when they saw Stark’s seemingly esoteric reworking of the signatures of two nineteenth-century German authors: “Maybe they responded passionately,” says Stark, “because what I’m doing in a lot of my work [is] having a kind of love affair with an artist’s voice…I’m just fascinated by the construction of interiority…[and] I love how literature can be mimetic and revealing at the same time.”1

This line of thinking allies Stark with artists she admires, such as Ed Ruscha or Raymond Pettibon or Barbara Kruger, for whom reading and looking become inextricably intertwined. But Stark is as preoccupied with the impact of the aesthetics of a given source—be it art, literature, or a live personality—as with its ostensible content. And unlike her older peers, she speaks in the first person: she likes to talk; she also likes to stare and is not above venerating her heroes, even as she is prepared to deconstruct and “dis” their attributes. Whatever the medium, she never lets you read an image or a text or a song or a celebrity within her art without insinuating herself as subject: she has the heightened sensitivities, insistent intimacy, and emotional indulgence of a teenager. “Maybe those kids were responding to the touch of my drawings,” she said to Cooper, “because it’s not creepy or ironic.” But as Cooper noted, Stark “clarified” those adolescent impulses and “fashioned a practice” from the feelings a while back. The close grip that she maintains on adolescent acuity becomes her craft and an aesthetic. Part of the visceral, emotional appeal of her art hinges on her ability to hold fast to the fugitive intensity of her associative mind, to keep an obsessive tug between love and uncertainty in scary tension.

You can see this when she re-presents a source to us in her own art. I remember how struck I was a couple of years ago, when I encountered a life-size, mixed-media-on-paper drawing of Stark’s from 2008. Indebted to Egon Schiele’s erotics, I think, but explicitly to Francisco de Goya, it pictures a single, near-naked woman (whom I want to believe is Stark herself) balancing a simple wood chair on her head and sporting a pair of opaque black stockings, a sheet over her head, and not much else. The translucent sheet only makes the red of her nipples and the tidy black lozenge covering her “sex” all the more arousing. And once she gets us peering into the sheet, we also see the confounded look on her face: a perfectly rendered expression of the guilt and pleasure that a girl posing naked under a sheet with a chair on her head—and an artist painting herself as a girl posing naked under a sheet with a chair on her head—might reveal. Stark lifts her title, but also her play on words, from a print from Goya’s Los Caprichos, Ya tienen asiento (They've Already Got a Seat, 1799), in which two women wearing nothing but transparent petticoats and balancing chairs on their heads are taunted by a gallery of men observing their bare bottoms. Stark’s title, “If conceited girls want to show they already have a seat…“ (after Goya), lets us know what she thinks of girls who presume upon their nakedness (and looks). At the Hammer, Stark serves less as subject than as mediator, though her modus operandi is still one of insinuation. As Houseguest curator, she is working with prints and drawings from the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, images all, though text remains a factor via their titles. And the staring and intimacy that she has cultivated in her art are here in force.

When Stark invited me to write in response to the works that she has assembled here, she was intent on banishing any implication of an overarching narrative. “I personally don’t think visual essays are stories, which is why they are visual, obv!!!” she wrote at the outset of an extended e-mail exchange. “So there is no ‘narrative’ per se … there are touch points and personal references and motivations and associations etc.…but those do not a story make!”

She needn't have worried: the images clearly don't tell any single tale, save possibly of the preoccupations of one Frances Stark. But they do sustain a psychosexual intensity and a rhythmic momentum propelled by Stark's alternation between dense and emotionally charged and spare and emotionally attenuated images, as well as her carefully orchestrated counterpoint between introspection, laugh-out-loud satire, and frightening revelation. Single-figure character studies, such as Edgar Degas’s famous aquatint Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: Painting (1877– 80) (“Degas is saying ‘This woman is at a museum,’” says Stark) or Elizabeth Bishop’s Reaching for the Coat Sleeve (1943), a poignantly witty genre study of a perky sophisticate caught in an awkward move (“Note the drapery,” Stark suggests. “She could be decrepit, but the peak on her hat and the heels of her shoes make you know that’s not so. Such a fine line between beauty and bum.”) bracket Goya’s astonishing Carretadas al cementerio (Cartloads at the Cemetery, 1863), in which we get one last stare at the near-naked body of a still-beautiful prostitute—one of many, the title tells us, lest we lavish too much attention on the single woman we see. Goya makes us look at the dead woman here guiltily, as if at porn. It is porn: she is held unceremoniously by the ankles by one of several undertakers, awaiting her turn to be dumped from a wheelbarrow into the tunnel opening reserved, it seems, for this purpose. Only Goya, or maybe Stark, would lavish as much attention on the large ass of the undertaker, bent over the tunnel that he labors to load with victims, as he does on the dead woman’s bare legs and voluminous remnant of a dress.

Against Goya's powerfully implicating representation, Stark inserts Paul Flora's delicate, almost abstractly restrained Ornamental Bird (1961), an image that leaves her as quiet as the caged creature (“How can you talk about it?” she asks). Jean Veber’s soapoperatic lithograph The Head of the Family (19th century) shows its subject dead-drunk on the couch, under the defiant gaze of his wife: a stereotype or two with an endearing odd detail, in this case the man’s implausibly long arm, falling off the couch as he sleeps, another phallic allusion. Stark ends, though, with what feels like a clearing of the palette or plate: Degas’s etching On Stage (1876), a weird but beautifully enigmatic glimpse of a backstage scene, likely untoward, “wiped” not clean but imperceptible, the marks of an erasing cloth obscuring the image witnessed. And she follows Degas with one of only two works by women here—Bishop's is the other—Agnes Martin's untitled color offset lithograph of simple horizontals from 1998.

Stark's selection begins with a “signature” pickle—not Heinz, but Mike Kelley. Kelley’s long-standing appeal within the Los Angeles artists' community is not exactly comparable to that of a pickle, but he’s at least as relished as an L.A. artist’s artist. “Mike was my teacher,” says Stark, intimating an anxiety of influence. Stark is also a teacher now, and one of the questions that role has posed for her is “What can be taken as obvious?” In Kelley’s drawing, the big green pickle hovers over a circular black-and-white pool, which makes the image conspicuously phallic. Or does it? Stark says that when she showed this and other works from the exhibition to her students, none of them talked about sex.

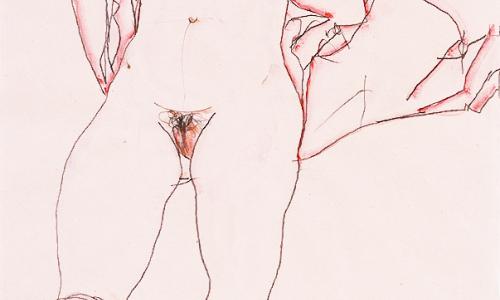

Stark's traverse of history, and of historically and culturally and pedagogically distinct modes of representation and emphasis, is liberated to the point of almost willful titillation—as in the juxtaposition of a darkly private, Rembrandtesque portrait by Anders Zorn of a woman mending, Repair (1906), and a pale and spiky line drawing by Anton Lehmden, Colosseum (1959–61). The Babel-like public-spectacle space of the Colosseum becomes inescapably vaginal, in contrast to the voyeuristic rendering of the voluptuous seamstress, mending alone in the dark. On the cover of this brochure, the symbolism of Lehmden's etching is heightened that much further, juxtaposed as it is to Schiele's explicitly erotic, almost painfully delicate gouache and pencil drawing of 1913, Girl with the Purple Stockings (and, we can’t help but notice, the red-stained kneecaps, lips, and vulva). That in-your-face eroticism is picked up by Stark, along with Schiele's sharp black against red, in her selection of a more mechanically cool, Picabiesque nude, a 1964 “carbon” drawing by Alain Jacquet, titled simply AC. And Stark makes certain that we don’t miss the junior-high sexual punning in William Hogarth's hilarious, finely etched hairpiece inventory, The Five Orders of Perriwigs (1761). “An ad!” she says. “For wigs!” The way they are displayed as merchandise was the selling point; the kicker was the little hand/finger pointing to a bizarre phallic protrusion on a wig smack-dab in the etching's center.

It occurred to me that Stark points to the obvious—in this case, the sexual innuendos—as a kind of accent: the laugh-out-loud details animate her underlying trains of thought. But there is a governing awareness, if not quite a thesis, here too: an assertion of female sexuality and strength pictured in moments of recognition—the furrowed brow in Beham’s Female Genius or the assertive hand on hip in Schiele's “so-there” sisters. It is also there in the horror of Goya's Carretadas al cementerio, the image that most powerfully unnerved and moved me—and, obviously, Stark: “You know, looking at Goya's picture, I had the strangest reaction, a kind of scary identification. I instantly imagined all the other live ones back on the job. It has to do with the fact that when you see her dead…she is still the ‘thing,’ the body that was her asset.” Stark adds: “When I first saw the picture, it made me think of two things: Berlin Alexanderplatz—I suddenly understood how Franz Biberkopf gives up on selling tie fasteners on the street and decides to pimp women—and then of a crazy apocryphal story about my great-grandmother possibly being a woman with “clients.” The way Goya draws this, with his title, makes you think that much more vividly about using your body for your living…you know, ‘the oldest profession’?”

What struck me most immediately about Stark's selections overall was the preponderance of women in the mix—almost all rendered, however, by men. This was coupled with an almost percussive sense of pattern and repeat—hands behind the backs of figures, heads with funny hats, pairs of legs arched for an artist’s academic rendering, exaggerated attitude and anatomy—a counterpoint to the obliqueness of Stark's associative chains of thought. I wrote to Stark: “The business of women (you) looking at women (the subjects of many of these images) through mostly male renderings, and complicating the sexuality of the gaze as a result, really interests me. Am I off base here? I want to think about the variety of ways in which sexuality is used in each of these images.”

And on further reflection, I added: I just perused the images again: so unexpectedly poignant, given the overtness of the sex and the aggressive rhythmic repetitions you use to tie it all together and insist on our attention. I can’t find any overarching link save for melancholia. The erotic pitch, however, is intense, and doesn’t ever sag or abate. It’s interesting, too, that this is so clearly the work (meaning your selections) of a woman. I’m not sure what’s making me say this. Maybe it’s that melancholy, in its Renaissance/ baroque incarnation as melancholia, was so Dürermale, and in our post-AIDS era, [it’s] so hard to extricate melancholy from its identification with that illness. You’ve got those fantastic Beham women posed in poses usually reserved for the male of the species: Melancholia, most conspicuously, but also Female Genius Holding a Coat of Arms. Shocking, actually, that little Beham etching of a woman genius!

“I am,” I confessed to Stark, “very susceptible to melancholy.” It’s the mood I think that best cuts through the potential consumer co-optation of any other representation of desire right now. It’s a feeling, not a look or a pose. We’re no longer thinking about gaze here. We’re in there with the artist and his or her subject.”

Notes

1. Dennis Cooper, “Openings: Frances Stark,” Artforum 35, no. 8 (1997): 80.

Linda Norden is a curator who also teaches and writes about art, currently based in New York. Between 2008 and 2010 she was director of the CUNY Graduate Center’s James Gallery; she was previously curator of contemporary art at the Harvard University Art Museums (1998–2006) and taught at Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies (1992–98).

This exhibition has received support from the Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley.