Hammer Projects: Tom Marioni

- – This is a past exhibition

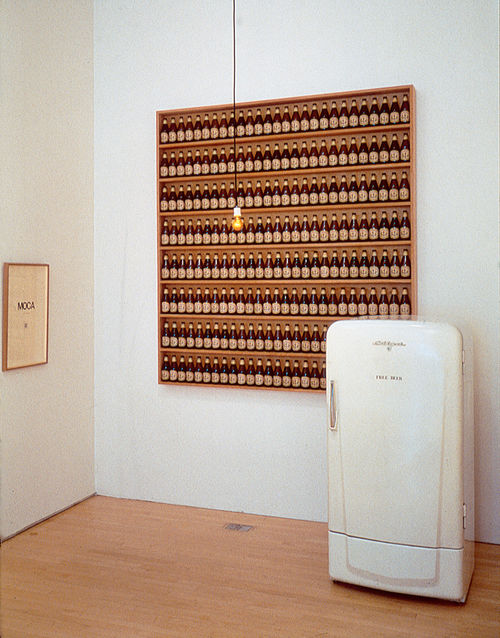

For over forty years, Tom Marioni has been experimenting at the boundaries of art. His first art action—One Second Sculpture (1969) in which he released a coiled metal tape measure into the air and allowed it to fall to the ground—encapsulated Marioni’s desire to eradicate the distinctions between sculpture, music, drawing, and performance by embodying all of the genres at once. A key figure in the invention of Conceptual Art in the 1960s, Marioni’s identity as artist, writer, and curator also defies categorization. In 1970, he founded the Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco as a venue to support his own work and that of his friends and colleagues, and he has published his writings in various periodicals and books. Through the decades, Marioni has continued to, in his words, “observe real life and report on it poetically,” amassing a body of work comprised of drawings, prints, actions, and writings that articulate his desire to unite people and ideas. For his Hammer Project, Tom Marioni will present his on-going artwork Drinking Beer with Friends is the Highest Form of Art. Along with the bar-like installation and remaining empty Pacifico beer bottles from private gatherings he will host as part of the piece, the exhibition will feature a selection of Marioni’s drawings and ephemera, including two site-specific wall drawings made for the occasion of the exhibition.

Organized by Hammer senior curator Anne Ellegood.

Please note that the beer salons held in conjunction with Marioni’s project are by invitation only, in accordance with the wishes of the artist.

Biography

Tom Marioni was born in Cincinnati in 1937 and lives in San Francisco. He was a key figure in the emergence of Conceptual Art in the 1960s, and he founded and ran the Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco from 1970 to 1984. In 1981 Marioni was honored as a Guggenheim Fellow, and he founded the Art Orchestra in 1996. Since 1963 his work has been the subject of numerous one-person exhibitions, including The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art, Oakland Museum of California (1970); The Museum of Conceptual Art at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1979); Cutting the Mustard, Le Consortium, Dijon, France (1984); The Germans, the Italians, the Japanese, Museo ItaloAmericano, San Francisco, and Yoh Art Gallery, Osaka, Japan (1987); The Artist’s Studio (Starting Over), Capp Street Project, San Francisco (1990); Golden Rectangle, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2004); and Tom Marioni: Beer, Art, and Philosophy (The Exhibition) 1968–2006, Lois and Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, Cincinnati (2006). Marioni’s work has been featured in thematic exhibitions internationally, and he has staged his performances and actions at venues around the world. He was the founding editor of Vision Magazine in 1975 and is the author of Beer, Art, and Philosophy: A Memoir (Crown Point Press, 2003) and other publications.

Essay

By Corrina Peipon

In 1970 Tom Marioni was invited to make an exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California. He asked sixteen friends to come to the museum on a Monday evening, when it was closed. The curator brought enough beer to go around, and everyone “drank and had a good time.”1 The empty beer bottles, tables, and chairs were left in situ for the run of the exhibition. Rather than a performance, The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art (1970) consisted of an action and its evidence. “Since I didn’t want to subject my friends to being performers, the public was not invited. . . . It was an important work for me, because it defined Action rather than Object as art. And drinking beer was one of the things I learned in art school.”2 At the start of the same year, Marioni had founded the Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA) in San Francisco, where he presented work by artists—including himself, under the pseudonym Allan Fish—experimenting with new art forms, such as conceptual art, sound art, performance and action art, installation, and video. Open to the public as a nonprofit, membership-driven museum, MOCA presented pioneering exhibitions and projects until 1984. In 1976 Marioni started Café Society, a Wednesday afternoon social club that met at Breen’s Bar, down the street from MOCA, where invited guests assembled to drink beer and talk about art. Evolving out of The Act of Drinking Beer, Café Society was a social artwork that brought people together under contrived circumstances to interact freely. Café Society has continued over the years in various iterations, including video screenings with free beer at MOCA and Marioni’s ongoing weekly Wednesday salons at his studio.

Marioni distinguishes his beer events from art receptions or parties through rules and aesthetics that define the space as art, including restricted guest lists, lighting, music, and a general ambiance of sophistication that he deems appropriate to an art experience: “I am a romantic and I wanted to try to recreate the café scene of artists and writers in Paris in the 20s. I thought of Café Society as drunken parties where ideas are born.”3 In keeping with this sentiment, when Marioni moved his beer-drinking salons to his studio, he renamed the event The Society of Independent Artists, after an organization that Marcel Duchamp helped found in 1916, which ironically rejected one of the French artist’s seminal works from its annual exhibition in 1917.

With his readymades—works that consisted of things like a bicycle wheel mounted atop a stool (Bicycle Wheel, 1913) or a urinal tipped on its back and presented on a pedestal (Fountain, 1917)—Duchamp set the stage for the evolution of art from a uniquely devised and contained symbolic space into an expansive field in which anything can be art if the artist deems it so. By privileging actions over objects in works such as The Act of Drinking Beer, Marioni became part of a rich tradition of artists who have eschewed contrived procedures of constructing representational spaces in order to develop their work out of the residue of the everyday. In 1960 artist Yves Klein and cultural philosopher Pierre Restany coined the term nouveau réalisme (new realism) to describe art that was emerging throughout Europe. Rather than simply representing real or imagined spaces, the new realists, influenced by Duchamp and responding to contemporary urban life, instead used real objects and experiences to construct their work. For his 1958 exhibition Le Vide (The Void), Klein removed everything but a cabinet from the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris and painted the entrance and hallway in his patented International Klein Blue. Guests were served blue cocktails. The social conventions of the art opening became the work, revealing the exhibition space and the audience as loaded constructs that are not neutral but integral to the existence and interpretation of art.

The conviviality that pervades Marioni’s work is also present in the work of Klein’s friend and fellow new realist Daniel Spoerri. For his 1963 exhibition 723 Utensils des cuisines (723 Kitchen Utensils), Spoerri transformed the Gallery J in Paris into a restaurant, instating himself as the chef and various prominent art critics as the wait staff. Guests were invited to dinner and instructed to create “Trap-Pictures” with their empty plates and glasses after the meal, encapsulating a moment with the remains of an activity. Spoerri did not consider the act of making the work to be the work, maintaining the status of the object as the final artwork. In the 1950s Allan Kaprow began to explore the possibility of a new kind of art developing out of abstract expressionism. Influenced by Jackson Pollock’s method of action painting, Kaprow gravitated toward the act of making a painting more than the painting itself, and in his 1958 essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” he called for the overthrow of objects by actions. The following year, Kaprow presented 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, in which guests wandered amid various structures as participants danced, painted, squeezed oranges and drank their juice, and recited texts from hanging scrolls. Kaprow rarely documented his Environments and Happenings, and the works were always dismantled, producing few permanent records or objects. The works remain only as scores or instructions and in the memories of those present. Like Klein and Spoerri, Kaprow was interested in eliminating boundaries between art and life, leading to a redefinition of social hierarchies within the art experience.

Kaprow’s activities parallel and overlap with those of his contemporaries in Fluxus, a loose constellation of international artists who incorporated sculpture, performance, music, and text into poetic and often humorous artworks. Influenced by Duchamp as well as composer John Cage—a close friend of Marioni—and his ideas about indeterminacy, many Fluxus artists embraced the potential of chance by engaging participants in nonhierarchical performances or creating situations in which spontaneous interactions could occur. As a result, the works are located in the specific space and time of the enactment of the piece, changing with each iteration or interpretation of the work and dependent upon the participants and the setting.

Simultaneous to and coalescing with the rise of Fluxus was the emergence of conceptual art, wherein the artist follows predetermined rules to produce an artwork, privileging ideas over objects. Combining this mode of production with that of an action or Happening, The Act of Drinking Beer depends on indeterminacy to generate art arising from prescribed conditions. While the work has an articulated set of rules to which all the participants, including the artist, are subject, an action involving more participants than the artist alone opens a broader field of possibility, thereby creating a community. Marioni describes The Act of Drinking Beer as “invisible art,” an idea he credits to Klein and that also encompasses works such as Cage’s famous silent composition 4’33” (1952). Klein clearly articulated his intention to make invisible paintings as an introduction to Le Vide (The Void)—which Marioni recreated in 1980 for an exhibition at Gallery Paule Anglim in San Francisco—but his tone can be read as facetious. In Marioni’s earnest interpretation, invisible art is art in which the materials and constraints, as well as the intentions of the artist, are not readily apparent in the work but encompass everything present within their scope.

Between 1968 and 1972 Marioni made only actions, turning away from object making in reaction to the increased commodification of art. A seminal work from this time is One Second Sculpture (1969), in which he released a coiled measuring tape into the air, allowing it to unfurl and fall to the ground, producing an action, a sound work, and a drawing through a simple operation that incorporated space and time. When he returned to making objects, he devised conditions that maintain a nonhierarchical relationship between the objects and the actions required for their making, defining both the process and its result as the artwork. Invited to Scotland for an exhibition in 1972, Marioni staged a performance in the gallery over five days, four of which were spent making “action drawings that produced sounds.”4 Drum Brush Drawing, included in this exhibition, is one in an ongoing series of process drawings that Marioni began during that performance, in which he spent two hours “drumming” with a jazz drummer’s steel brushes on a large sheet of fine-grained sandpaper, resulting in an abstract image that resembles a bird in flight. Out-of-Body Free-Hand Circle—done on-site for this exhibition and one of a series initiated in 2007—also enlists productive limitations, in this case the length of Marioni’s arm and the diameter of the circle that he is able to produce by engaging its full range of motion.

Marioni is a lifelong fan of jazz, and his process is reminiscent of the form, establishing structures within which improvisation may occur. The repetition required to make these works—like some music—is intended to induce a hypnotic or meditative state. Paralleling the symbiotic relationship of process and result in Marioni’s work, the practices of art and meditation are unified and always present, even when they are invisible.

Notes

1. Tom Marioni, Beer, Art, and Philosophy: A Memoir (San Francisco: Crown Point Press, 2003), 93.

2. Ibid., 93.

3. Guillaume Desanges, “Tom et moi (Exchanging emails with a stranger is the highest form of art criticism),” Trouble, no. 6 (2006), http://www.guillaumedesanges.com/spip.php?article30.

4. Marioni, Beer, Art, and Philosophy, 123.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, L A Art House Foundation, the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.