Hammer Projects: Stephen G. Rhodes

- – This is a past exhibition

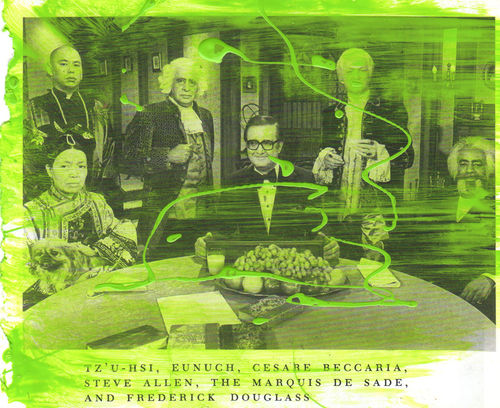

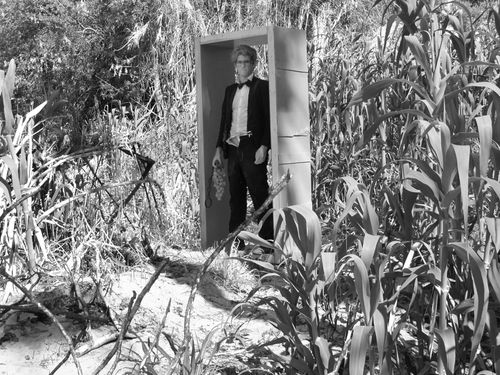

The multimedia installations of Los Angeles–based artist Stephen G. Rhodes darkly theatricalize the historical unconscious, borrowing strategies of pedagogical entertainment found in theme parks, period cinema, and museum displays. When Rhodes takes on a topic, he literally tackles it, ungluing the various parts (overt or subliminal) to reveal the underbelly of his subject. In the film installation on view at the Hammer—inspired by Steve Allen’s late-1970s television chat show, Meeting of Minds, which featured dramatized roundtable discussions among historical figures such as Cleopatra, Aristotle, Francis Bacon, Attila the Hun, and Emily Dickinson—Rhodes stages a collision of mediums, citations, and narrative contingencies, offering an impossible history lesson that must be negotiated both architecturally and cinematically.

This exhibition is organized by Ali Subotnick, Hammer curator.

Biography

Stephen G. Rhodes was born in Houston, Texas in 1977, raised in Louisiana, and currently lives in Los Angeles. He received a BFA from Bard College, Annandale, NY (1999), and a MFA from Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, CA (2005). Rhodes has exhibited widely in the U.S. and Europe and was included in Prospect 1 biennial, New Orleans, LA; The Generational: Younger than Jesus, the New Museum, New York, NY; and Between Two Deaths, ZKM Center for the Arts and Media, Karlsruhe, Germany. He was also featured in Second Nature: The Valentine-Adelson Collection at the Hammer Museum (2009). Hammer Projects: Stephen G. Rhodes is his first one-person museum exhibition.

Essay

By John David Rhodes

History is the iteration of our lack of purchase on totality. The fact that everything cannot be present to us underwrites and necessitates history as a representational practice. If we accept this assertion, we might go on to make two further observations: First, as an iterative practice, history must involve itself in an anxious redeployment and substitution of signifiers. (That is to say, history exists so as to be rewritten.) Second, as a practice that is haunted by the specter—the ghostly reminder—of totality, history accepts as its starting point that this totality cannot be made truly present to the reader of the historical text. It has become a commonplace to state that the past (especially a past that is traumatic) is “unrepresentable.” But this statement is untrue. The past is entirely representable, and history writing (whether in word or image) is its representation. Saying that the past is representable is, of course, not the same thing as saying that the past is actually, materially available to us. We part-invent it out of the evidence we find lying around, or else we make it up in order to contradict this evidence. It’s a game of art.

Stephen G. Rhodes's work grows out of the rich humus—which is to say, out of the rot—of historical representations that (over)populate the cultural landscape and the popular imaginary. Rhodes has devoted much of his work to the ludic excavation of historical wrongness. Here “fact” breeds and mingles with a promiscuous series of forms. In their mutual overabundance, both “facts” and forms court their own ways of being wrong, while they enact the unavoidable and necessary fact of representation itself.

For instance, in one of the earliest of his works, Instructions for a 16 Sided Barn: Your Shit Is in My Mouth (2001), Rhodes depends on the little-known and pointless historical fact of George Washington’s having designed a sixteen-sided barn. Because this fact doesn’t matter, Rhodes hypertrophies it into the only thing that matters. “George Washington” (played by Rhodes himself, who assumes the leading role in many of his videos) argues with his foreman over how many sides the barn is to have. (“Eight!” and “Sixteen!” are yelled over the drone of military drumming.) In the background, figures in white attempt haplessly to build the barn. These figures, of course, are spectral embodiments of slaves, and slavery, of course, is really the point here. Washington was a slaveholder—this is something we both know and repress. The story of Washington’s sixteen-sided barn, which is “true,” has nonetheless been absent from most common historical accounts. Its absence acts as an absurd analogy for the repression of our knowledge of Washington as a slaveholder. The joke exposes the absurdity of the repression itself.

Here and elsewhere in Rhodes's work, however, the point is never entirely the point. It is wrong to say that the work is "about" slavery or the historical experience of racist domination and the consistent, deliberate historical occlusion of the same. Rather than say that the work is about these historical traumas, better to say the work is strewn about the lacunar landscape of these experiences.

Rhodes's videos, sculptures, and other works are bound together by their mutual (inter)dependence on the “green screen” technology that acts as the medium of his aggressive seizure and reuse of visual materials (especially film and television footage). After shooting, the green-painted plywood boards—necessary for this mode of "special effects" production—are thrown around the studio, walked over, splattered, and otherwise abused. Rhodes then repurposes them as "found" lumber for the construction of sculptural installations and as the surfaces of collage works.

These works would devolve into formal preciosity were it not for the fact that the green screen assumes an allegorical relation to their thematic and political concerns. The images that we see can be seen only insofar as they cover over the "original" historical scene of Rhodes’s "original" performances. Just as historical representation makes visible by way of occlusion, so the green screen fixes the surface of one representation onto and/or on top of that of another.

Rhodes's slapdash use of green-screen technology produces an ectoplasmic haze that shimmers around or through the appropriated material affixed to his own footage. By dint of this sloppiness, the ethical and historical contents of the source materials are never sublimated; they are, rather—and rather literally—suspended. They hover in the videos and populate them like ghosts who have forgotten the purpose of their spectral malingering.

The work on view at the Hammer Museum, Receding Mind: Circle of Shit (2010), continues these formal and theoretical concerns. Here the point of departure is Steve Allen’s variety talk show Meeting of Minds, which ran on public television from 1977 to 1981. Its “guests” were actors who played the roles of historical figures, from Plato to Karl Marx to Attila the Hun. In choosing Meeting of Minds as his source material, Rhodes has self-consciously appropriated a practice of which his own work is a belated repetition.

The bald-facedness of Meeting of Minds' impossible varietal groupings suggests that its premise was anything other than a fantasy of presence, despite the fact that the show’s scripts claimed to try to stick, whenever possible, to the recorded words and writings of the guests. Rather, the show seemed to want to stage presence itself as fantasy. Think of the rhetoric of the variety talk show: "Tonight we have with us . . . " Meeting of Minds knew that it didn’t "have" anyone tonight. But given that any celebrity's appearance on any talk show is determined solely by that celebrity’s relation to and status as invested capital, it might be fair to say that no one has ever really appeared on a variety talk show.

The variety talk show operates via structural substitution. Rhodes marries this structural logic to the formal operations of structural cinema. Receding Mind is shot using a revolving camera. Rhodes’s “guests” are borrowed directly from Allen. Frederick Douglass, the Marquis de Sade, and the Empress Tz’u-hsi all contend angrily but rather stupidly with one another and with the impositions, layerings, and materiality of the green screen (which invites its own guests). The guests’ activity is registered via the impartial robotic indifference of the revolving camera, whose motion is doubled by the revolving apparatus of projection at the site of exhibition. We would be correct to make links—at least on a formal level—to the work of Michael Snow, whose La Région Centrale (1971) and Corpus Callosum (2002) employed mechanically revolving cameras that insist on the fleetingness of their purchase on the profilmic. Structural film has often been evoked by its critics and theorists as a mode of filmmaking that endeavored to make the projected film the analogue of consciousness itself. Like Meeting of Minds’ absurd, impossible guest roster, however, the belatedly modernist predication of structural film on the materiality of film itself is the index of the gap that will forever separate consciousness itself and the representation of its phenomenology. As Pier Paolo Pasolini remarked, “To make cinema is to write on burning paper."1

The figure of the historical "guest" operates in a manner similar to that of Ernesto Laclau’s "empty signifier."2 For a project of emancipation, both Frederick Douglass and the Marquis de Sade will do equally well as organizing placeholders. What will matter is the political content we pour into them. The point of the empty signifier is not that it remain empty but that it be filled, and refilled, as the exigencies of emancipation demand. Emancipation can come under any number of names and in many forms, but we will recognize the agents of domination and emancipation on the basis of their ideology (what they merely give shape to or make an opening for). The sheer proliferation of figures, models, actors, surfaces, and media in Rhodes's work bespeaks the need to conceive of our engagement with history as a scene of necessarily incomplete but nonetheless (and therefore) urgent making and remaking.

Notes

1. Pier Paolo Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise K. Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and L. K. Barnett (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 240.

2. Ernesto Laclau, "Why Do Empty Signifiers Matter to Politics?" in Emancipations (London: Verso, 2007), 36–46.

John David Rhodes is the author of Stupendous, Miserable City: Pasolini's Rome, the coeditor of On Michael Haneke, and a founding coeditor of the journal World Picture. He teaches film and visual studies at the University of Sussex.

Hammer Projects is a series of exhibitions focusing primarily on the work of emerging artists.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation. Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; L A Art House Foundation; the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.