Hammer Projects: Greg Lynn

- – This is a past exhibition

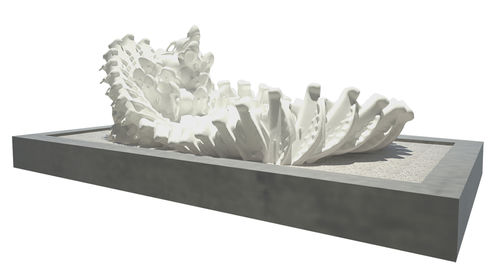

The Hammer Museum presents a new sculptural work by Los Angeles-based architect Greg Lynn. A fantastical attraction for visitors of all ages, Fountain is sited in the Museum’s outdoor courtyard. As the title suggests, the work is a functioning fountain made out of large plastic found children’s toys that have been cut and reassembled in multiple layers, with water spouting from its top and pooling at its base. Constructed with more than fifty-seven prefabricated plastic whale and shark teeter totters welded together and unified by the application of a white automotive paint, Fountain is a gathering place for the warm summer months.

Greg Lynn’s Fountain is the first architecture and design project guest-curated by architectural historian Sylvia Lavin. As part of Hammer Projects, Lavin will organize a new project approximately once a year over the next three years that will present new works by architects and designers. These projects will be sited in different locations around the Museum.

Organized by Sylvia Lavin, director of critical studies and MA/PhD programs in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA.

Biography

Greg Lynn was born in 1964 in Ohio. He graduated from Miami University of Ohio with degrees in both architecture (Bachelor of Environmental Design) and philosophy (Bachelor of Philosophy) and later from Princeton University where he received a graduate degree in architecture (Master of Architecture). He received an Honorary Doctorate degree from the Academy of Fine Arts & Design in Bratislava. Lynn’s innovative use of computer-aided design and robots to create complex forms has placed him at the cutting edge of architecture and design. In 2001 Time magazine named him one of its one hundred most innovative people in the world for the twenty-first century, and in 2005 Forbes magazine named him one of the ten most influential living architects. The buildings, projects, publications, teachings, and writings associated with his practice, Greg Lynn FORM, have been influential in the acceptance and use of advanced technology for design and fabrication. Lynn has received awards from the AIA and Progressive Architecture, was the 2008 Venice Biennale Golden Lion recipient, and was given the American Academy of Arts and Letters Architecture Award in 2003. He is the author of seven books and monographs and has taught throughout the United States and Europe, holding the position of studio professor at UCLA. He is currently Davenport Visiting Professor at Yale University.

Essay

By Sylvia Lavin

Youth is wasted on the young. —George Bernard Shaw

The great figures of modern culture, from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Pablo Picasso, celebrated youthful forms of expression and ascribed preternatural innocence to the child and, through association, primordial virtue to the artist. This romantic view of the “artist-child,” however, is belied by the complex stuff of childhood, none more deceiving than the toy. Toys are the first point of contact between a child and the manufactured world. Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother famously gave him Froebel blocks, commonly credited with inspiring the elemental shapes of the Prairie Houses, while whispering, “you will be an architect when you grow up.” Buckminster Fuller designed his first geodesic dome while playing with peas and toothpicks. Ray and Charles Eames modeled their entire design ethos on homo ludens, not only producing celebrated toys actually intended for children but also considering all their designed objects, from chairs to buildings, as toylike and defining play as the model of architectural use.

Toys are not innocent figures in the history of art but are rather theoretical objects that reveal the transition of things from one state to another: finger paint into painting, inflatable balloons into steel sculptures, and models made of peas into buildings made of complex polymers. Indeed, toys are particularly important to architecture because it is in the nature of the discipline for architects to work with buildings that exist first as models—in other words, at the scale of toys. Some architects—from Le Corbusier to Frank Gehry—become so invested in the model phase that they not only make hundreds of models for a single building but also avidly detour into industrial design, producing all manner of things, from spoons to chairs and coffee pots, because they, unlike buildings, can remain forever as model toys and full-scale objects simultaneously. Greg Lynn’s Fountain enters this tradition strategically rather than innocently, luring toy sharks and whales that would otherwise be destined for a landfill into the space of the museum not because they are the traces of an architectural purity that must be salvaged but because toys are where architectural ideas are most potent.

What do you want Brick? —Louis Kahn

Fountain literally pressures the toys, robbed of an innocence they never had, into a new conceptual order. The process of design and fabrication began with the selection of the toy type, which Lynn ideally sought to make on the basis of how many discarded toys of the same kind he could find. Second, a digital model was made of the toy in order to calculate which modifications to individual toys would permit a given number to fit together in as many different ways as possible while requiring the fewest changes to each unit. The process recalls what is called parametric design, the digital calibration of multiple factors into a system determined by some measure of optimal performance. In this case, the parameters were set by the modifications to the toys that would allow for the creation of an assemblage with maximum formal complexity and minimal manufacturing difficulty. Robots then carved each toy according to the parametric protocol, after which the mass-produced toys were manually welded together to produce a unique object. And it is precisely at this moment of transition between the digital and the mass, on the one hand, and the analog and the singular, on the other, that the conceptual upheaval begins to play out most dramatically.

What at first seems like an exercise in serial repetition actually involves the literal grappling with the difference between one shark and another. Even though they are all cast from the same mold, every shark is unique. Their differences—resulting from the temperature in the factory on the day a specific shark was made or the particular mixture of plastic or the consistency of the paint used in a manufacturing run—are not great enough to be seen by the naked eye, but they are detectable by a digital scanner and become increasingly significant as the effort is made to get one shark to nestle against another. In the end, the sharks resist the ease of construction promised by parametric design and must manually, and with force, be jiggled and jostled into position.

The process of design and manufacture discovers difference where there was presumed to be only sameness and uses this emergent differentiation to create an object that is singular and multiple all at once. The cusp between the serially produced and the handmade object is rendered even more acute by the fact that, unlike Lynn’s earlier recycled toy furniture series, in which each object was made from a single toy type, Fountain extends the exploration of identity and difference by joining several multiples: it is made of sixteen sharks, forty-one whales, and seventy of the trilobed units first made for Lynn’s Blob Wall and unifies them through the application of white automotive paint. Corresponding to the naturalistic rock formations used in baroque works as the architectural armature for figurative sculpture, these blobs of rustication and rocaille are Fountain’s building blocks. Indeed, they are bricks, prefabricated units that are mortared together to make a structurally integral plane. But unlike Carl Andre’s Lever (1966), for example, in which 137 bricks were laid out on the floor according to the intrinsic logic of their formal nature—in other words, in a straight line—these bulbous shapes come together in an undulating mass. Like Andre’s bricks, the blobs do have a formal nature but one that is engineered to produce variation. Louis Kahn famously instructed his students to follow the nature of materials by asking, “What does a brick want to be?” Lynn does not presume his bricks to have an essential nature that repeats from iteration to iteration. They instead perform a mute resistance to identity and conformity.

I’ll See It When I Know It —Greg Lynn

If the toy is not innocent and the bricks are not identical, what kind of whole do they add up to? Well, first of all, they make a fountain, a typology residing somewhere between architecture and sculpture and generally devoted to spectacularity, a display so overwhelming that it can fool the eye. In the baroque urban fountain, for example, from Bernini’s Triton to the celebrated Trevi Fountain, architects used visual legerdemain to smooth the point of contact between the city’s infrastructure (water was power in the seventeenth century and still is) and the pleasure of everyday life. Bernini, for example, would have you believe that a massive obelisk can float on air like a ray of sunlight. This tradition of the urban spectacle, which runs at least from the fountain to the panorama to contemporary LED billboards, is predicated on the idea that seeing is believing and hence that if you make something supervisible the viewer will believe just about anything.

The capacity of seductive images to push out thought itself is why critics such as Clement Greenberg vehemently opposed kitsch and its artistic reincarnation in pop and insisted on conformity to medium specificity.1 A very diverse group of contemporary artists, however—including Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor, and Jeff Koons—not only insist on occupying what Rosalind Krauss called the expanded field and the conceptual territory between sculpture and architecture but do so precisely in order to generate a new relationship between thinking and seeing.2 Their works deploy visual intensity to produce perceptual swerves that ask new questions—such as "what kind of object is this?"—rather than conforming to old thoughts. In the case of Fountain, in constant flux because of both the immediately visible action of the water and the not-quite-visible but still intricate and forceful variation of its parts, every act of seeing produces a different object. During each moment of watching, the fountain, is remade again and again, but in this case the story leads not to a fountain of youth and childhood but to a youthful fountain, in perpetual motion.

Notes

1. See Clement Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 3–21.

2. See Rosalind E. Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8 (Spring 1979): 30–44; reprinted in The Originality of the Avant-garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985), 276–90.

Sylvia Lavin is the director of critical studies and MA/PhD programs in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design at UCLA. She is the author of several books, including Form Follows Libido: Architecture and Richard Neutra in a Psychoanalytic Culture and the forthcoming Kissing Architecture.

Hammer Projects is a series of exhibitions focusing primarily on the work of emerging artists.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, LA Art House Foundation, the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.

Fountain: Greg Lynn has also received major support from the Brotman Foundation of California and Herta and Paul Amir.