Hammer Projects: Friedrich Kunath

- – This is a past exhibition

Like a favorite poem, Friedrich Kunath's works poignantly yet playfully distill the fundamentals of human emotion—desire, loneliness, and anxiety—creating comically tragic scenes in which human beings try to find their way in the world. Employing an impressive range of mediums—drawing, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, and a neon sign—Kunath will cover the lobby walls, creating a world both fantastical and quotidian revolving around a number of middle aged male characters struggling to define their lives in a sea of uncertainty.

Organized by Anne Ellegood, Hammer senior curator.

Biography

Friedrich Kunath was born in Chemnitz, Germany in 1974 and lives in Los Angeles. He was educated at Peter Mertes Stipendium, Kunstverein Bonn in Bonn, Germany and at Arbeitsstipendium der Jürgen Ponto-Stiftlung, in Frankurt am Main, Germany. Kunath’s work has been presented in one-person exhibitions at Kunstalle Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden, Germany; Kunstverein Hannover, Hannover, Germany; and Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, Colorado, and has been included in numerous thematic exhibitions such as the 11th Triennale für Kleinplastik, Fellbach, Germany; Grin & Bear It: Cruel humor in art and life, Lewis Glucksman Gallery, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland; The Eternal Flame, Kunsthaus Baselland, Basel, Switzerland; Life on Mars: the 55th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Learn to read, Tate Modern, London; and The Gravity in Art, De Appel, Amsterdam.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

The middle-aged male protagonist who questions how his life has unfolded and ponders the ways in which he might fulfill unmet desires or control his destiny is commonly found on the printed page, in television dramas and sitcoms, and on celluloid. Think of Willy Loman's desperately paradoxical attempts to cling to his loathsome work as a salesman and to imagine a different life for his family in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. Consider Alexander Portnoy, of Philip Roth's Portnoy's Complaint, and his struggles to understand his simultaneous longing for the steadiness of family, religion, and history and propensity for disillusionment and rejection. Remember the seething rage of the injured Brick in Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof? Or the confused contempt that prompts Lester Burnham to take up weight lifting in his garage as he lusts for his daughter’s best friend in American Beauty? Picture Bob Harris trudging around his hotel in Lost in Translation, weighed down by regret and failure. And laugh at Seinfeld’s George Costanza and his perpetual attempts to find the missing pieces of professional and personal satisfaction in the puzzle of his life.

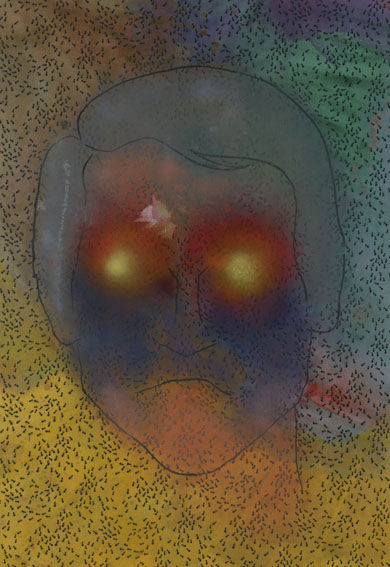

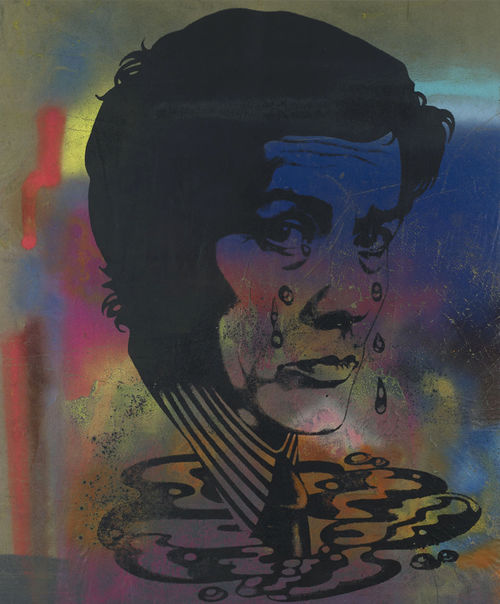

Male figures—often alone, gazes downcast, briefcases in hand, clouds overhead, amid the chaos of nature or tethered to their desks—are the centerpiece of Friedrich Kunath’s installation in the Hammer Museum’s lobby stairwell. The artist has transformed the space into a sort of private men’s club with walls covered in pin-striped and plaid gabardine and corduroy fabrics and densely hung with paintings portraying middle-aged men in various states of turmoil or transition. While the array of individuals on view may bring to mind the walls of portraits found in the Harvard Club or other exclusive settings indicative of social status, Kunath’s depictions are not portraits per se, and they do not follow any typical painterly style aimed at the faithful representation of a subject. Rather, these canvases depict the “everyman” found everywhere in our society, rendered in a variety of drawing styles atop layers of colorful watercolor washes and dark clouds of ink, occasionally accompanied by a handwritten text. Painted in simple, illustrative black outline or in silhouette, sometimes silk-screened onto the canvas, Kunath’s men are more type than specific persona, and yet they are profoundly familiar to us. Despite their nature as caricatures and the humor of their cartoony expressions of emotion, these characters conjure embattled feelings of sympathy (and its complicated cousin, empathy), sadness, ennui, resentment, and disdain, prompting us to see beyond their mere outlines and to consider our reactions to them seriously. For however bloated and ubiquitous the stereotypes of the “midlife crisis” may be in our culture,1 there is a truthfulness to the search for meaning that inevitably accompanies each individual life’s journey. And it is this search—this looking upward, this scratching of the head, this trudging forward through a chaotic landscape, this climbing stairs into the unknown—that Kunath features again and again in his work.

Kunath’s ongoing investigation into the nature of identity seems to encompass centuries of philosophical debate and visual art—from metaphysics to German romanticism, from existentialism to painterly abstraction, from postmodern schizophrenia to gender politics—while remaining somehow cheekily skeptical of all efforts to pinpoint the myriad cultural influences and natural inclinations that inform our senses of who we are. We can locate a range of references to visual artists in his prolific output—the washy pours of paint recall color-field painters such as Morris Louis; the self-deprecating but endearing humor shares a sensibility with David Shrigley and others of his generation; and the concern with the vulnerability of man when faced with the vastness of the world brings to mind the inventive Dutch conceptualist Bas Jan Ader—but Kunath’s work takes up broad questions about the role of the artist in society more than it explicitly addresses any specific precedent. The freestanding painting located on the lobby landing, melancholically titled If the phone don’t ring, you’ll know it’s me (2007), could be a metaphor for the artist. As the artist works, he gradually paints himself out of the picture. The work becomes less about him and more abstracted, and in the process, it takes on the potentiality of resonating more broadly. Kunath’s men are appealing to us in part because they are nonspecific. They could be anyone: your father, your grandfather, your brother, your boss, your best friend. They could be you . . . and perhaps that is why we feel we know them so well. One of the sculptures on view features the phrase “I am goodbye” (borrowed from a Will Oldham song) captured in neon, suggesting that the end (even a temporary ending) of an emphasis on the subjective opens up lots of space. Good-bye to one means hello to another.

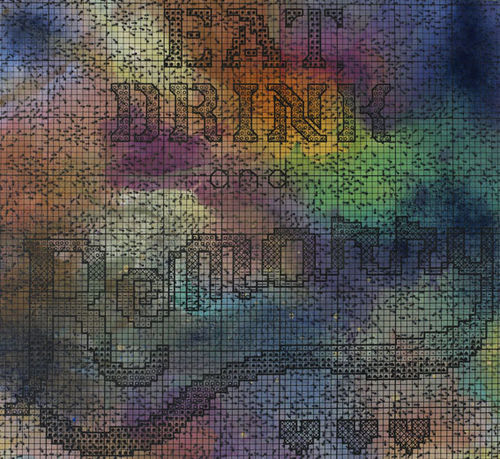

Kunath creates environments steeped in absurdity, humor, and a magical balance between the possibility of a nearly paralyzing humanist crisis and an incredibly stoic and even playful optimism. The gravity of the struggles portrayed is tempered by whimsical aphorisms—“I lost you but I found country music” and “Eat, Drink, and Remarry,” which look on the brighter side of failed relationships—and a consistently sunny palette replete with blue skies, hopeful sunrises, and propitious rainbows. The difficulties of daily life and finding one’s way amid seemingly endless obstacles are made explicit in Kunath’s work but always within an atmosphere that is inherently hopeful. This cast of middle-aged men may be slumped over, expressions of worry and fear creasing their brows, but they remain standing nonetheless. They are nothing if not resilient. They may be alone (save for being surrounded by their anxieties) and perhaps even lonely, but they are not tragic. The sun sets, suggesting an impending dark shadow over the brightness of daylight, but it is always followed by a sunrise. If we are all doomed to be alone, the artist seems to suggest, why not do it together? Welcome to the salon de Friedrich Kunath, where, to borrow the artist’s title, we are all in this alone.

Notes

1. A slew of recent films and TV programs highlight the continued fascination with this subject matter: TNT’s new series Men of a Certain Age and the films Up in the Air, Last Chance Harvey, Everybody’s Fine, and The Bucket List are just a few examples.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, L A Art House Foundation, the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.