Hammer Projects: Eric Baudelaire

- – This is a past exhibition

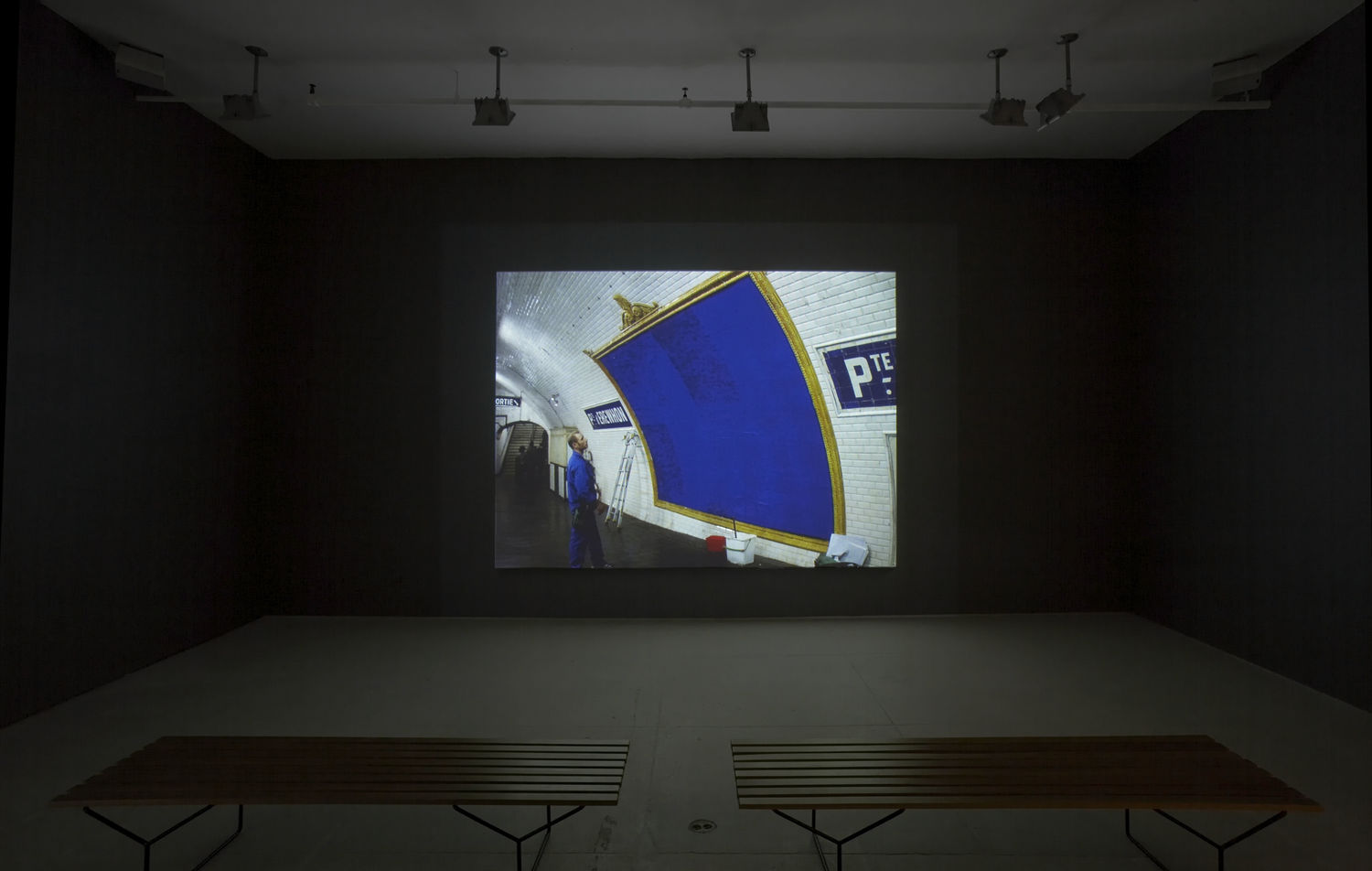

In his first U.S. museum solo show, Paris-based Eric Baudelaire will present his video Sugar Water (2007). The action takes place on a Paris metro platform where a billposter covers a large advertising billboard with a sequence of images that depict a car parked on a Parisian street that bursts into flames, becomes swallowed up in smoke, and then remains only as a skeleton of the former car. Using a laborious traditional system to mount the details of each image, this cinematic event gradually unfolds over the 72-minute film, offering a slow contemplative consideration of political violence as a counterpoint to the rapid barrage of images we typically experience in our news media. Despite its slow, nearly meditative pace, Baudelaire creates a haunting and provocative work that completely absorbs the viewer.

Organized by Anne Ellegood, Hammer senior curator.

Biography

Paris-based artist Eric Baudelaire was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1973 and graduated from Brown University in 1994. His work has been the subject of one-person exhibitions at Elizabeth Dee Gallery in New York and galleries in Europe as well as at the Musée de la Photographie, Charleroi, Belgium, and Gallery TPW, Toronto. His work has been included in numerous thematic exhibitions such as Concrete Eruditions, Le Plateau / FRAC, Paris, France; Great Expectations, Casino Luxembourg, Luxembourg, France; and Replaying Narrative, Le Mois de la Photo, Montreal, Canada. Baudelaire’s exhibition at the Hammer is his first one-person museum exhibition in the United States.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

A remembered event is infinite. —Walter Benjamin1

Long before the events of September 11, 2001, there was another terrorist attack on Wall Street. On September 16, 1920, an Italian anarchist named Mario Buda, angry over the recent executions of fellow ideologues Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, parked his horse-drawn carriage, filled with one hundred pounds of dynamite and five hundred pounds of cast iron, on the corner of Wall and Broad Streets in downtown Manhattan, across from the J. P. Morgan Company offices. Buda then left the neighborhood, and soon thereafter the handcrafted bomb exploded, killing close to forty people, injuring dozens more, and causing enormous damage to the buildings in the vicinity. Nearby, leaflets were found that read, "Free the Political Prisoners or it will be Sure Death for All of You!"2 It was the deadliest attack perpetrated in the United States up to that time, and the first incident to involve a car bomb (the carriage being the “car” of its day), a now-common strategy for getting explosive devices into vulnerable locations undetected. These days, car bombs are detonated on a regular basis, but we usually associate them with countries experiencing war or civil strife, such as Iraq and Lebanon. Few would likely guess that the first such attack took place on American soil.

A car-bomb explosion is the subject of Eric Baudelaire’s quietly cinematic and deeply engrossing video Sugar Water (2007), which calls attention to the ways in which mass media’s repetition and distillation of images can instill a numbing indifference to these frequent incidents. At the same time, Baudelaire methodically deconstructs and undermines the means by which the media has allowed this estrangement to take place. The action occurs on a Paris metro platform, where a billposter covers a large advertising board with a sequence of images that depict a car parked on a Parisian street bursting into flames, then being engulfed in smoke, and finally ending up as a charred skeleton. The billposter uses a laborious traditional wheat-pasting technique to mount the details of each image, so that the event gradually unfolds over the course of the seventy-two-minute film, offering a slow, contemplative consideration of political violence as a counterpoint to the rapid barrage of images that we typically experience in our news media.

For the past several years Baudelaire’s work has explored the relationship between photographs and the events that they depict. With a particular emphasis on the production, circulation, and consumption of images produced in conjunction with incidents of violence and aggression, his work is less an indictment of the “society of the spectacle” and more an argument for the way that mechanically or digitally reproducible mediums serve to fragment and prolong events (and, importantly, our memories of them) rather than assembling them into comprehensible totalities that would allow us to digest and move on from what has occurred. In his Blind Walls series of 2007, Baudelaire photographed the façades of buildings in Paris and covered them with sheets of transparent Plexiglas that had been spray-painted with graffiti. Appropriating tags that he had seen on the streets of Lyon when he visited there in 2006, the layered texts express a variety of emotions about the events of September 11, 2001: “I hate Ground Zero,” “I need Ground Zero,” and “I claim Ground Zero.” The subjectivity of these statements reveals that a public event can profoundly affect individuals, even those physically far removed from the “scene of the crime” (psychological distance and geographic distance being wholly distinct from each other), but it also suggests a kind of fatigue with the ever-present and continually repeated reminders of a monumental occurrence such as this. The transposition of the graffitied sentiments onto buildings in Paris also serves to remind us that while the enormous loss and tragedy enacted upon the site now known as Ground Zero can never be diminished, places around the world have likewise suffered the traumas of erratic and brutal uprisings, including, indeed, the streets of Paris, which have witnessed revolutions, protests, gang violence, and, yes, even car bombs. The specificity of time, location, and action gives way to something more akin to shared experience, tinged with a kind of collective ennui. As Claire Gilman has written of Baudelaire’s work, “The present opens onto a silent and irretrievable past.”3

Shot on a set, Sugar Water takes place in a fictional Paris metro station called Porte d’Erewhon. The name is borrowed from Samuel Butler’s 1872 satire of Victorian society, Erewhon, in which time is frozen. Baudelaire hired a real billposter to lay down the imagery, but the commuters who move in and out of the station are all hired actors, enacting a sort of role reversal in which the person upon whom the single camera focuses is not an actor, while the “extras” who fill the background are. At the beginning of the video, the billposter carries a ladder and his supplies down the metro stairs, walks to a large advertising board surrounded by a decorative gilded frame, and begins to work. First he lays down an image of a parked car, and then he begins to unfold and systematically apply the imagery. Each photograph consists of eight details, and the billposter works from the top left corner, inserting columns of imagery from left to right, until the completed picture is in place, at which point he begins again. Once the slow reveal of the car bomb explosion and smoldering aftermath has been accomplished, he once again covers the billboard with a blue background—like the blue screens using in moving image media to serve as a blank space before imagery is inserted—and the video loops, returning us again and again to the depiction of the car bomb.

Baudelaire’s intense prolonging of an event that would take only moments in real time creates a sort of extreme analog version of the well-known cinematic technique of slow motion, which has the effect of keeping us perpetually in the present. The sequence of events is chronological, but the process of painstakingly putting down one image after another—the repetition of wetting, folding, unfolding, and pasting—is surprisingly entrancing. It is an endless act of both revealing and covering over, enacting representation and obliteration simultaneously. While the billposter works continuously (and increasingly absurdly if we consider the site as one for expensive advertising), the commuters around him take absolutely no notice of the disturbing narrative that he is putting on view. Their indifference can be thought of as a commentary on how our ever-increasing inundation with images has taught us to simply disregard them as the wallpaper of the urban landscape, but it might also be understood as a sort of protective shield. When representations of violent incidents are repeatedly flashed before us, we sometimes need to shut them out in order to be able not only to process them but also to believe them. The inherently reductive nature of photography, whereby an entire sequence of events is distilled into one iconic image; its removal, both spatially and temporally, from actual experience; and its capacity for duplication can engender feelings of skepticism. Today we see innumerable photographic images on a daily basis, and we often don’t know if what we are seeing is “real,” even when it is being presented in ostensibly indexical mediums that support a documentary function.

Unlike the commuters on the metro platform, however, the viewers of Sugar Water are positioned with a direct view of the billposter and encouraged to watch him for as long as we like. Baudelaire has titled his video after the description by French philosopher Henri Bergson of duration as an invisible process, analogous to sugar dissolving in a glass of water. In Bergson’s articulation of the relationship between time and space, he argued that duration is mobile and fluid.4 Despite his use of metaphors like sugar water, he believed that duration was largely indescribable, something that would always remain incomplete, and it is this state of incompleteness—this eternal return, this presentation coupled with erasure—that is at the heart of Baudelaire’s practice. Like Bergson, Baudelaire differentiates between the types of memories that are inscribed through rote repetition (and increasingly reiterated with the support of photographs) and the “true memory” that stems from the initial experience and is understood to be immune from repetition.5 Baudelaire’s work questions what happens to a culture that creates collective memories by widely circulating particular images—just think of how the image of the jet flying into the first World Trade Center tower now encapsulates the entirety of the event—and suggests that we may only be beginning to understand how photography interfaces with reality.

Notes

1. Walter Benjamin, “On the Image of Proust,” in Selected Writings, vol. 2, pt. 1, 1927–1930, ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 238.

2. Although this case has never officially been solved, historian Paul Avrich has argued that Buda, who like Sacco and Vanzetti was a follower of the Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, was responsible. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mario_Buda.

3. Claire Gilman, “Eric Baudelaire,” Frieze, no. 111 (November-December 2007): 190.

4. Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell (New York: Henry Holt, 1913), 9–10.

5. See Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory, trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott Palmer (New York: Zone Books, 1988).

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, L A Art House Foundation, the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.