Larry Johnson

- – This is a past exhibition

The Hammer Museum presents the first full-scale survey exhibition of work by the Los Angeles-based artist Larry Johnson. Johnson's work is quintessentially of and about Los Angeles but at the same time forms a penetrating commentary on American culture more broadly. He combines an immaculate glossy surface with witty and at times cutting references to popular culture, animation, gay subcultures, and moderne architecture. Much of his work explores the themes of Hollywood and celebrity, especially the edges of that world, where aspirations and fantasies bump up against reality. Johnson received his masters of fine arts from CalArts in 1984, and he has always been among the most respected artists of his generation. He makes use of a sometimes bitter humor and draws on stylistic elements taken from sources such as animation, graphic design, commercial illustration, and advertising. A range of Johnson's work from throughout his entire career is presented, from his early text-based works through his well-known winter landscapes, and on to his most recent works featuring cartoon animals. Curated by Russell Ferguson, Hammer adjunct curator and chair of the Department of Art, UCLA.

Essay

By Russell Ferguson

For twenty-five years Larry Johnson lived, without a car, in a part of Los Angeles known variously as mid-Wilshire or Koreatown. Traces of the city, and of this neighborhood in particular, can be found throughout his work. Johnson has always also lived in another Los Angeles, one in which street hustlers are picked up on the corner by men who shower them with gifts, figures like John Sex and the porn star Leo Ford have their names in lights, cartoon logos step off the wall to have their photograph taken, and politicians star in made-for-TV movies. But it is often hard to tell the difference between these two worlds. Reality keeps confusing them. It is where these two worlds overlap that Johnson has found the room to take stock of a whole range of issues that run like veins through his work, including death, celebrity, class, camp, lust, nostalgia, and obsolescence.

On his mother's side, Johnson's family was straight out of The Grapes of Wrath. In the 1930s they came out to California from dustbowl Oklahoma and found work in the canneries. His mother grew up in a trailer park and eventually became a beautician. His father was a Teamster truck driver who rose before dawn to deliver bread for a big bakery. In 1950s California these were jobs that for the first time offered access to a middle-class lifestyle. The Johnsons lived in Lakewood, a 1950s development built around a gigantic shopping mall, whose official motto was "Tomorrow's City Today." Larry Johnson was born there in 1959. Joan Didion wrote about Lakewood in the early 1990s, when a national scandal erupted around the sexual assaults committed by the high school "Spur Posse." She places the town's birth in "the seamless confluence of World War Two and the Korean War and the G.I. Bill and the defense contracts that began to flood Southern California as the Cold War set in. Here on this raw acreage on the flood plain between the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers was where two powerfully conceived national interests, that of keeping the economic engine running and that of creating an enlarged middle or consumer class, could be seen to converge."1

Although Johnson's father, like many in these new, virtually all-white suburbs, was politically right wing, to the point that he voted for the segregationist George Wallace in the election of 1968, the family also identified with the Kennedys, who were emblematic of a prosperous America in which the working class could aspire to upward mobility. The family had a lawn for their kids to play on, and Johnson's father cut it every week with his King 0' Lawn mower. As the Spur Posse case would later demonstrate, high-school athletes were idolized and privileged. Indeed, in Didion's words, towns like Lakewood "were organized around the sedative idealization of team sports."

Larry Johnson, however, was the kind of kid who asked for and received Kenneth Anger's Hollywood Babylon as his seventeenth-birthday gift. He was already a regular at the opera and at the Mark Taper Forum, the Los Angeles theater named after the real estate developer who had founded Lakewood. When it was time for college, he enrolled at CalArts, where he got his BFA in 1982 and MFA in 1984. His early efforts there were cartoonish abstract paintings based on architectural elements. "Big, ugly Liquitex affairs," is how Johnson describes them now.2 After a couple of years he stopped painting and started making collages of domestic scenes into which he inserted himself alongside Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. His primary mentor was the conceptual artist Douglas Huebler, whose use of language in his work was a key influence. Huebler's art comic, Crocodile Tears, which ran in the LA Weekly in the 1980s, has some of the knowing tone that characterizes much of Johnson's work. An early supporter was Richard Prince, and Johnson and Prince have continued to share a fascination with celebrity, jokes, and the markers of class in America. The dedications Johnson solicited from Rip Taylor, John Sex, and Leo Ford, as well as the elaborate joke in Untitled (Dead + Buried) (1990) testify to a shared field of interests.

In 1986 Johnson was included in David Robbins's iconic Talent, his matinee-idol looks juxtaposed with equally glossy headshots of Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons, and Ashley Bickerton, among others. The work that had launched Johnson to early prominence was Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds) (1982/84): six photographs, each with a deceased movie star's name superimposed on cotton-wool clouds floating on a blue background. Johnson wanted to make a work that would appeal to those at CalArts who were oriented toward structuralism, but also to those who, like himself, were not quite so theory driven and who were more attracted to pictorial work. He made a piece that was driven by language, but specifically by the language of our time, the language of celebrity. As Johnson puts it, "To master celebrity is to master language."3

On one level the clouds represent Hollywood heaven; on another they suggest the opening credits of a movie. The stars in Johnson's pantheon are Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift, Natalie Wood, James Dean, and Sal Mineo. The first three starred in The Misfits (1961), sometimes said to be a "cursed" movie. Gable died of a heart attack right after filming ended, and Monroe and Clift met early deaths after unhappy lives. The last three starred in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Although Rebel Without a Cause is the earlier film, it feels later—the first film of the "new" Hollywood—while The Misfits can be seen as one of the last of the "old" Hollywood pictures. In any event, Wood, Dean, and Mineo continue the theme of untimely movie-star deaths. The series as a whole was prompted by the death of the last of the six, Natalie Wood, who drowned in 1981.

Of the group, Mineo is the only one who did not achieve the status of a huge star. He comes last. But last is a special place on this list. On occasions when only one of the series is shown, Johnson insists that it be Mineo. And it is Mineo who marks the connections between Hollywood celebrity, hustling, and violence that Johnson will return to repeatedly in later work. In 1976 the thirty-seven-year-old Mineo was stabbed to death in an alley behind an apartment building in West Hollywood. The details of his death have never been fully explained.

In 1985 Johnson brought the Kennedy family into this mix with Untitled (Grief Is Devastating), a two-panel work in which the text was taken verbatim from a TV Guide description of a two-part mini-series on the life and death of Robert Kennedy. Although his work seems quite simple, its formal elements are more complex than they might first appear. Drawing a lesson from the work of Ellsworth Kelly, Johnson treats the wall as a kind of page on which to compose. The diptych combination of vertical and horizontal components feels slightly awkward, and deliberately so. Johnson objects to the semiotic model that posits vertical as portrait and assertive, and horizontal as landscape and passive. Here the two formats are simply stuck together, in a combination that might perhaps be called passive aggressive.

Johnson stresses that the work is not about Bobby Kennedy, at least not directly: "It is not the story of anything except a movie." Johnson's interest is less in events themselves than in events as they are filtered through the machinery of mass culture, cleaned up, glamorized, and sold back to us as entertainment. On this level the Kennedys are just another kind of star. Yet the work is also unquestionably about the Kennedys specifically. "I think about the Kennedys at least once a day," Johnson told me, and his interest in that era-Camelot, so-called- is evident throughout his work, especially in the way that politics became increasingly a part of pop culture. "I'm not the one who named my administration after a hit Broadway musical,"4 but the fascination remains, with the Kennedys certainly, and with the era more broadly. The cover he designed for the catalogue of his 1996 exhibition at the Belkin Art Gallery in Vancouver is a black and blue version of the cover of John Stormer's neo-McCarthyite, Kennedy-era rant None Dare Call it Treason (1964)."5 And Johnson also follows the Kennedy story from the heroic period of the myth into its more ambiguous later stages. The past and present are linked together in Untitled (Peter Lawford) (1995), in which Lawford, Rat Pack member and brother-in-law to President Kennedy, is yoked together with Arnold Schwarzenegger. "Here's one," the text begins, but the supposed joke turns out to be all too close to the truth. Untitled (Greek Tycoon) (1986), consisting of two panels, one light and one dark, gives us the story of Aristotle Onassis. While the composition recalls the work of Josef Albers, one of many references in Johnson's work to classic modernism, the text this time is taken from a popular compendium of celebrity deaths called How Did They Die.6

The fact that Johnson apparently owned this book is perhaps significant in itself, suggesting a fascination with death that is even more apparent in Untitled (Black Box) (1987). Here the text is taken from the black-box recording of a plane that crashed into the Potomac River just outside Washington in 1982, killing seventy-four, including the pilots. If the line, "Larry, we're going down, Larry," from the transcript suggests a connection to the artist, it may not be totally fortuitous. Johnson's focus on death in this period was inescapably related to the AIDS epidemic. But Johnson's goal here, exemplified by the work's bright, multicolored lettering on a literal black box, was not to indulge in an empathetic grief but rather to ''brighten up death a bit." For him, the real tragedy is not the fact of death but "the inability of language to deal with death." The constantly changing lettering in many of Johnson's works from this period suggests a deep suspicion of smoothly flowing language as any source of authority. Instead, language is often treated as something purely visual, even decorative. In this way the predominately text-based works push back against their apparent meanings.

Language is reduced to a stuttering minimum in Untitled (Heh, Heh) (1987), the entire text of which reads: "Heh. Heh, heh ... Ah yes ... HA, HA ... HA, HA, HA." The source here is an advertisement in the New York Times for the columnist Russell Baker, but the content suggests language at the point of breakdown, a colorful snigger replacing more coherent communication. It would be hard to read any significance—any content at all—into this string of grunts and laughs. It is only Johnson's choice of this text, one might say, that makes it a text at all. The formal presentation of these words in a frame, exhibited as art, gives the text a formality and presence that forces a certain seriousness, a certain expectation of attention from the viewer, despite the complete triviality of the content. For Johnson, evidently, the distinction between major and minor, between a presidential candidate and an in-the-know laugh track is all but meaningless. This work was made when Ronald Reagan was president. When the president could be an actor whose greatest skill was in conveying a plausible geniality, what else was there to say, perhaps, but "heh heh?" Gore Vidal, whose own oeuvre has evenhandedly encompassed both Aaron Burr and Myra Breckenridge, remembers in the late 1950s casting his play The Best Man, set at a presidential convention. "An agent had suggested Ronald Reagan for the lead. We all had a good laugh. He is by no means a bad actor, but he would hardly be convincing, I said."7 Ah yes.

With the large diptych Untitled (John-John and Bobby) (1988), Johnson again projects onto the Kennedys, but for the first time he wrote the story himself rather than using a preexisting text. Actually, this fragment from the hustler life doesn't have to be about the Kennedys at all, although the choice of the names John-John and Bobby make the connection unavoidable, and the opening sentence's reference to John-John's "nipples as round and rare as Kennedy half dollars" drives the point home. Although the text seems like a couple of almost arbitrary moments pulled from a longer narrative, the two panels refer to specific ideas that had interested Johnson for a long time. In the left panel he addresses the idea that the unconscious is fully formed by the age of four. In the right panel a story of early Hollywood—that the Keystone Kops filmed their stunts in the middle of real traffic passing by—is transposed into the register of a low-budget pornographic videotape. What unites these apparently disparate ideas is the question of spontaneity. How much control can we really have over impulses rooted in childhood events? How much of what we think of as unpremeditated action is really preprogrammed? The constantly varying colors of the lettering force the viewer into a kind of stumbling, slowed-down reading.

Untitled (John-John and Bobby) was part of a body of explicitly gay work that Johnson showed at 303 Gallery in New York in 1989, an exhibition that was influential for a number of other gay artists. Although Johnson had been out of the closet to his family since he was a teenager, this exhibition felt to him like a more public coming out. The media in the late 1980s dwelled on Rock Hudson's death from AIDS and the panic over "Patient Zero." For Johnson it felt like a political necessity to be publicly out.

But the work also had a particular locus: the hustler stretch of Santa Monica Boulevard with which Johnson had become familiar in the early 1980s. The text for Untitled (I Had Never Seen Anything Like It) (1988), in which the "highly successful actor" Quint Vantage pulls up in his Jaguar XKE to ask "How far you going?" is taken from Gregg Tyler's book The Joy of Hustling ("The unabashed confessions of a boy who knew them all—the rich, the beautiful, the talented—and some of them paid for the experience").8 This world where hustlers routinely rub up against Hollywood stars was an alternative universe with just enough reality in it to offer believability, at least for those who wanted to believe, and the exact proportions of fantasy and reality always remain a little in doubt. "He said that he thought that I could be a star, like, you know, a young Bert [sic] Lancaster, you know. He mentioned a lot of names. He said Burt Lancaster. He said Clint Eastwood. He said Fess Parker." So reads the testimony of Paul and Tommy Scott Ferguson, convicted of murdering Ramon Novarro at his house in Laurel Canyon in 1968. Seventeen-year-old Tommy "said that he had been unaware of Mr. Novarro's career as a silent film actor until he was shown, at some point during the night of the murder, a photograph of his host as Ben-Hur." The older brother, Paul, meanwhile, explained his occupation: "A hustler is someone who can talk–not just to men, to women too. Who can cook. Can keep company. Wash a car. Lots of things make up a hustler. There are a lot of lonely people in this town, man."9 Again, fantasy and harsh reality are uncomfortably blended. How much do the clients, the stars, buy into this vision of the world, of their world?

In 1994 Johnson would return to hustler territory in Untitled (Standing Still & Walking in Los Angeles). The work is an homage to Frank O'Hara, modeling its title on a phrase from his "Ode to Causality" (1957-58): "standing still and walking in New York."10 O'Hara's poetic use of countless details from the everyday life of his period, personal references, and in-jokes is an approach that resonates very widely in Johnson's work. Untitled (Some Details with Dandruff Circled) (1995) is a good example of a work replete with such references. The transposition he makes here, however, is not just from New York to Los Angeles but specifically to the sidewalks of Santa Monica Boulevard, where, to avoid trouble from the police, hustlers have to appear to be walking somewhere while actually remaining close to a particular spot, essentially standing still and walking at the same time.

But as O'Hara said of John Rechy's novel City of Night (1963), "The hero is a hustler, but the author is not."11 Fiction is fiction, no matter how rooted in autobiography, and it would be a mistake to blend the many first-person voices in Johnson's work with his own voice. My Dad Is My Hero, several works announce, but the voice that says it turns out to be Nancy Sinatra's. We can, however, hear Johnson speak for himself in the transcript of his court testimony reproduced in Untitled (Q &A) (1988), tracing his path from the Motherlode bar across Santa Monica Boulevard to a liquor store. His crime: jaywalking. Johnson discourages overt identification with himself. "I would deny any autobiographical content" is how he puts it. But perhaps that "would" leaves just a little ambiguity. In the words that Charles Dickens gave to David Copperfield, "Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show."12

But what pages? The text in Untitled (The Friends You Keep and the Books You Read) (1988) concludes, "I decided to take a look at this business." In the context of the other works in the series, we might assume that the business is hustling. And it is, in a way, but the actual source is a testimonial to the Amway Corporation from one of its salespeople. The real testimonial, of course, is to the supposed power of language to effect a social upgrade, both "to get some of those luxuries that the budget never leaves room for" and to gain intellectual credibility. The piece is in part a jab at the many pseudo-intellectual artists who in the late 1980s flaunted their reading lists as a kind of credential. Johnson remembers being asked patronizingly if he knew who Jean Baudrillard was. He did, but, unlike his interlocutors, he felt no need to parade the fact. Implying that those who do are on the level of deluded Amway salesmen bent on self-improvement, he forces "high" theory onto the same page with the most debased of commercial texts. In Untitled (Five Buck Word) (1989) the five-buck word in question is "emollients," the perfect choice for those who want language to smooth their way to advancement. "In 1975 Paul Ferguson, while serving a life sentence for the murder of Ramon Novarro, won first prize in a PEN fiction contest and announced plans to 'continue my writing.' Writing had helped him, he said, to 'reflect on experience and see what it means.'"13

In 1989 Progressive Insurance commissioned work from a number of artists, including Johnson. His contribution, Untitled (Don't Drink and Drive, Wintergreen + Orange) (1989) has a text that concludes with "a gigantic fireball ... incinerating any human in its path." Appropriate for an insurance company, perhaps, but also for a nihilistic frenzy. The work's title invokes a vapid, insurance-friendly slogan. In this case, it is advice that Johnson himself follows. Reversing the usual pattern, however, he drinks but doesn't drive, and hasn't since 1986. In Los Angeles, of course, not driving is unusual to the point of eccentricity. Drinking, however, is a universal phenomenon, and it is by no means missing from Los Angeles life. ''I'd rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy," Dorothy Parker is supposed to have said, and Johnson included the aphorism in Untitled (Some Details with Dandruff Circled), sourced via Jackie Curtis. Johnson has an encyclopedic knowledge of the bars in Hollywood and Koreatown. He illustrated his Vancouver catalogue with photographs of some of them, and the endpapers featured his drawing of a particular favorite, The Blacklite. Johnson no doubt agrees with Luis Buñuel's statement that he "can't count the number of delectable hours I've spent in bars, the perfect places for the meditation and contemplation indispensable to life."14 And Buñuel concurs with Johnson, ending pages of ecstatic praise for bars, smoking, and drinking with a cynical bromide: "Finally, dear readers, allow me to end these ramblings on tobacco and alcohol, delicious fathers of abiding friendships and fertile reveries, with some advice: Don't drink and don't smoke. It's bad for your health."15

Heroin is bad for your health too, and in Johnson's work it makes its appearance in a barrage of alliteration in Untitled (H) (1990), where we meet a "homo hipster" whose "hard-core habit and hard-fought holler for help hailed from the hallowed halls of higher learning." His complaint, quoted verbatim from a real episode of the TV show "Hard Copy," was that of an acquaintance of Johnson's, whose excuse for his addiction was the pressure of life in the Ivy League (or "the LV, League," as Johnson calls it). Apart from the "Hard Copy" quote, Johnson wrote the text himself, as would be his practice from this point on. He had begun writing these short, fragmentary narratives, and, he felt, he "needed an environment for these texts to exist in." The texts themselves felt rather cartoonish to Johnson. And so, for the first time since the cotton-wool clouds of Untitled (Movie Stars on Clouds), a series would feature imagery alongside the text. The texts needed a frozen environment, it turned out, a combination of Hollywood animation background and the idealized winter landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige. To make it, Johnson used as his primary source a winter scene lifted from a Viewmaster disc of Hanna-Barbera's "Scooby-Doo." In this predigital period Johnson had a day job producing network graphics for television, so he was familiar with how to put together painted eels, mylar, and colored paper to make a convincing whole to be photographed. Into these landscapes fall the texts, like abandoned placards. Or like paintings. Just as earlier works like Untitled (Grief Is Devastating) had used a multiple-panel format to make the wall function as a background, the texts in the winter landscapes assert a pictorial presence against the picturesque context in which the artist has placed them.

While the different works in this series share a memorable look, one that positions itself precisely against the cult of good weather that Los Angeles was built on, each has its own distinctive character, albeit one partly determined by the mood of the texts. Untitled (W, X, Y, +Z) (1990) thus takes place in a silent, Chekhovian winter. Untitled (Jesus + I) (1990) is a perky, Bambi winter. Innocent in a breezy way, the text is also a testament to a total collapse of identity (including any religious identity) under an avalanche of consumer products. The theme is picked up again later in Untitled (Shopping Bags) (1995), featuring bags from the Bambi Bakery and Baby Deer Shoes. The text for Untitled (Winter Me) (1990) was written after reading Zsa Zsa Gabor's autobiography, "written for me by Gerold Frank," and the camp landmark Little Me, the story of Belle Poitrine.16 As in Untitled (Jesus + I), identity is dissolved into commodity. This is celebrity run amok, and the text panel itself has grown to enormous proportions, dwarfing what little remains of the landscape. In Untitled (A Quiet Life) (1990) narcissism is doubled, the twin mountains of the background echoing the strange tale told in the text. Drawing on many twin narratives, including Thomas Tryon's novel The Other17 (perfectly named to tweak the same people at whom The Friends You Keep and the Books You Read was directed), the tale ends with a reference to the artists McDermott & McGough, who in the 1980s in New York chose to live in an almost completely Victorian environment.

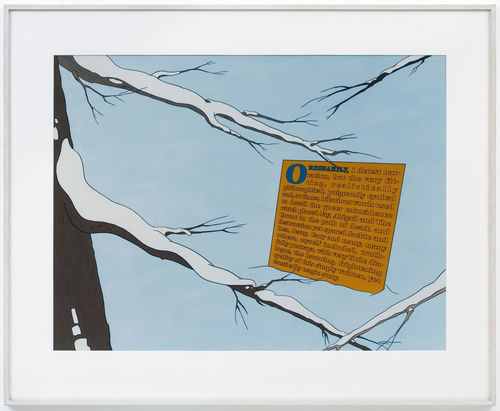

The last of the main series of winter landscapes was Untitled (Classically Tragic Story) (1991). The classically tragic story in question is the murders of the actress Sharon Tate and others committed by followers of Charles Manson. The Manson killings are seen by many as the dystopic conclusion of the expansive era that began with the Kennedy administration. For Didion, "Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled."18 At various times Jerzy Kosinski, Cary Grant, and Jacqueline Susann, among others, were said to have been (or said themselves that they had been) invited to the Tate home on the night of the murders, but for various reasons had not gone. Johnson puts his finger on the unarticulated desire to have been there, to have been touched by this nexus of celebrity and psychopathic violence. He understands the way such incidents become narratives, almost myths. Johnson himself, as a teenage boy, "tried out my first driver's license by making a pilgrimage to North Cielo Drive."19 Untitled (Classically Tragic Story) is perhaps the most elegant of all the winter landscapes. The text panel is seen through snow-covered branches against a clear blue sky. The disjunction between the sordid sub text and the clarity of the pictorial treatment makes the overall effect somewhat disorienting and all the more haunting.

Even more disorienting is the series of negative winter landscapes that Johnson made in 1991. Like Richard Hamilton, who in the late 1960s made a painting and a series of prints titled I'm dreaming of a white Christmas, based on a color negative of the Bing Crosby film of the same name, Johnson had (independently) observed that the color reversal can actually intensify the effects of the original. It was a phenomenon that Johnson had first noticed when he saw a color negative of a Japanese print, and discovered "Hokusai looks more Hokusai in negative." In Johnson's negative winter landscapes the glossy black that now occupies the snowy areas is as beautiful as the original white but infinitely more sinister.

The following year Johnson produced two blue landscapes. One, Untitled (Ghost Story for Courtney Love), is a nocturnal winter landscape in which the text panel floats freely in the sky. Its repeating text is wildly distorted in a style reminiscent of the prints made in the 1960s by the Los Angeles nun Sister Corita. It reads, "You can't stop and smell the roses with amphetamine psychosis." Johnson is a great admirer of Love, who made the remark to a friend of his. As a partisan of Love's, he had made some stickers attacking Madonna in 1990, when attempts were being made to position her as a major movie star in Dick Tracy. "Nobody Wants To See A Movie With Madonna In It" they read, in what turned out to be a fairly accurate assessment. In 1995 the text returned in Untitled (A Popsicle Stick with Some Writing on It / Prediction 1990). While these works are highly contemporary in their points of reference, the other blue landscape, Untitled (Ghost Story #1), plunges into a melange of nostalgic triggers from the 1930s to the 1980s. The text used in this work was originally made for an exhibition in Hanover of billboards by artists, with the text translated into German. The nostalgic basis for the work came directly out of being asked to show in Germany. For Johnson, America had a shared past, a continuity that could act as a series of reference points. "In Germany the common past was unspoken, a moment of disavowal." The trauma of the Nazi era blocked American-style nostalgia for an imagined, shared, past. Despite all the ambiguity with which he treats it, the history and self-image of postwar America everywhere in Johnson's work. It is the raw material that he shapes into his own narratives.

The evocation of nostalgia and the way it can be used to shape culture leads directly into the question of camp. One of the key techniques of camp is to recuperate elements of the outmoded—whether those may be faded stars, idiosyncratic turns of speech, or interior decoration—and turn them into revalorized signifiers. "The camp effect is created not simply by a change in the mode of cultural production," Andrew Ross has written, "but rather when the products of a much earlier mode of production, which has lost its power to dominate cultural meanings, becomes available, in the present, for redefinition according to contemporary codes of taste."20 Camp, then, is inextricably linked with the otherwise obsolete. Untitled (Albatross' Nest) (1995) gives us obsolescence in waiting, a whole nest of albatross eggs, potential embarrassments that we might never be able to get rid of.

Johnson's relationship to camp is closely linked to both politics and language. For him, "camp has a strong political position, a powerful one, because it changes language." He also stresses the fact that camp and camp language only exist as a product of and response to a fundamentally discriminatory system. It turns exclusion back on itself. "My relationship to camp is strictly as a secret language," he says. "Its makeup and context are meant to exclude. I honestly believe my work is different for gay men of my generation than it is for other people." At the same time, Johnson understands that camp itself may be on the edge of becoming outmoded, citing as an example the migration of the term "drama queen" from specific subcultural meaning into everyday speech.

A certain camp repurposing is behind Untitled (A Mensa Halloween) (1993). For a few years Johnson was for some unknown reason receiving mail from the Los Angeles chapter of Mensa, "the organization for smart people," including their newsletter, L.A. Mentary (or Lament, as Johnson refers to it). He became fascinated by the way in which this newsletter for supposedly highly intelligent people seemed to be devoted to petty squabbles, including one protracted argument about a Halloween party. Like most people, Johnson deplores the practice of "air quotes"—indicating quotation marks with the hands—but the profligate use of quotation marks here more or less enforces air quotes. "How can the quote on the page become the quote in the air?" he asks himself. The style of the text evokes the camp tone, again, of Little Me, which is littered throughout with arch quotation marks.

In Untitled (The Perfect Mensa Man) (1994), Johnson concocted a Mensa personal ad written in an Italianized version of pig Latin, in which everything ends in "ina": exactly the kind of elaborately tricky thing that would appeal to members of the group. The ad is floated on a background of stripes taken from Paul Rand's design for the packaging of IBM's first personal computer. Johnson loves Rand's work, and as early as 1984 he had made a video with an animated text titled Paul Rand's Women, 1948. "Rand is what I call modern," Johnson says, although his real interest is in the decline from modern into that very Los Angeles style called moderne, derived in part from art deco. Untitled (Something Quite Atrocious) (1995), with its off colors and broad stripes, is a moderne smashing together of Mary Poppins and West Hollywood: supercaliforniafaggotexpialidocious.

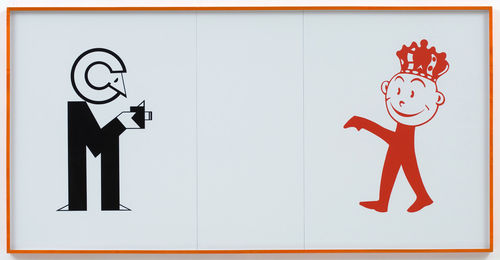

Equally moderne is the array of signs depicted in Untitled (Nathan Lane) (1998). Derived from a former Mayfair supermarket at Fifth Street and Western Avenue, now a Korean market, the signs in Johnson's version proclaim "Nathan Lane," followed by an ambiguous yes and no. At the bottom a florid signature by Johnson asserts his authorship. A decidedly unmodern (and unmoderne) figure introduced by Johnson to Mensa Halloween is the logo figure of the King 0' Lawn, making a reappearance from Johnson's childhood memories. He returns the following year in a standoff with his counterpart from the Morgan Camera shop on Sunset Boulevard in Untitled (Morgan Camera and King 0' Lawn) (1994). The work is a rendering of labor relations: on one side the happy, self-satisfied king, who is being photographed, on the other the sad-sack working stiff who takes the picture. The rather modern, Constructivist look of the Morgan Camera man only emphasizes the confrontation with the jovial, rotund King. The space of representation is the blank panel between them.

An apparently empty panel also begins the triptych Untitled (Storyboard) (1995). Although Johnson's work is full of language, it also pursues a parallel investigation of pictorial strategies, and the empty panel here is equally readable as a brown monochrome abstraction. The middle panel, in which a blurred Los Angeles Times newspaper enters from the upper left, might then be read as a kind of action painting. And the third panel, in which the newspaper has safely arrived, could be Pop. But reality sneaks up on this reading. "Southside Slayer Strikes Again," the front-page headline screams. The Southside Slayer, now believed to have been four different men, was linked to as many as eighty deaths in the 1980s and 1990s, but, since the women in question were mostly poor black prostitutes and crack addicts, the case did not—unlike, say, the Manson killings—really receive this kind of attention from the press.

Dave Hickey has written that Johnson's work is "about as far from 'cultural critique' as one can get,"21 but the evidence suggests otherwise. Johnson practices a very precise cultural critique, and unlike all but very few American artists, his critique is rooted in a politics of class. Johnson's broadly Marxist point of view had been in place since he took up reading the New Left Review as a teenager, and his class consciousness is evident in Untitled (Why Say High School?) (1994), in which the text concludes, "when you can say Choate." Gary Indiana has identified this work and the related Untitled (Noblesse, Oh Please) (1994) as "addressed to the kind of asshole who, having grown up with money and gone to the right schools, aspires to creephood and manages through long ugly study to achieve it."22

Perino's Restaurant was one of the great Hollywood hangouts of the 1940s and 1950s, frequented by both Bette Davis and Bugsy Siegel. From 1950 it occupied a spectacularly elegant building on Wilshire Boulevard designed by Paul Williams, with a peach and pink interior. It had already been closed for more than ten years when Johnson made Untitled (Perino's Front, Perino's Rear) (1998). Pointedly, he depicted both the front and the rear of the building: the front, where celebrities and gangsters came and went; and the rear, where Johnson once had sex in the alleyway next to the trash cans. It is a melancholy work, evocative of faded glamour and the recklessness of youth. From this moment there is a backward-looking element in Johnson's work that is different, more personal, than his earlier invocations of shared cultural history. I am reminded of Guy Debord's elegiac farewell:

Neither I nor the people who drank with me have at any moment felt embarrassed by our excesses. "At the banquet of life"-good guests there, at least-we took a seat without thinking even for an instant that what we were drinking with such prodigality would not subsequently be replenished for those who would come after us. In drinking memory, no one had ever imagined that he would see drink pass away before the drinker.23

The year 1998 was also the last that Johnson would make his work by having his maquettes photographed. From this point on all his work would be digitally scanned. Untitled (Land w/o Bread) (1999-2000) is on one level an homage to Luis Buñuel and his film of that title, but at the same time it is a farewell to the old technique, marked by fingers getting in the way of the lens. The fingers that block out most of the image also suggest the artist as omnipotent, as God in fact, but an arbitrary, clumsy, destructive God. Their intrusive presence stands for the remnant of the camera, and thus for the representational authenticity that photography has always implicitly claimed, here turned into a cruel joke, with a smirking goat poking its head around the obstruction.

Untitled (Unfinished Fome-Cor Factory) (1999-2000) also reflects on a type of production, in this case the ubiquitous foam board that is used by artists both to make models and to back photographs. The image somewhat resembles Ed Ruscha's Course of Empire series of paintings, made in 2005 after his earlier Blue Collar series from 1992. Both artists use optimistic candy colors to portray an industrial infrastructure on the edge of obsolescence, in a town that has always been monomaniacal in its obsession with the future. In Johnson's case the image is given an extra twist because the model for the FomeCor factory is the American Linen plant on La Brea Avenue. At one time Johnson's father drove a truck for American Linen.

At this point Johnson stopped making work altogether. An impulse that he had always had to some extent, a desire to simply withdraw from the world, including the world of making art, became irresistible. In particular, he did not want to turn his own work into a commodity to be produced on demand. He did, after all, control his own means of production, and he had to take responsibility for that. "I just was terrified," he says, "of getting into the position of making Larry Johnsons." The giant signature on Untitled (Nathan Lane), it turns out, was a warning shot to himself as much as a self-advertisement.

During this hiatus in his production, he continued to teach at Otis College of Art and Design, where he was a highly influential faculty member for many years. The artist Joe Sola was a teaching assistant for Johnson, and he remembers realizing that "this man's mind could speed along from one image to another with voracious speed and verbal precision unlike anyone I had met."25 Johnson's reputation among other artists only continued to grow, so that he is now considered an "artists' artist," a dubious honor that pairs respect from one's peers with neglect by a broader art public. Works that acknowledge him from artists such as Pae White and Nate Lowman are merely among the more visible examples of the wide-ranging influence of a practice that has remained vital to many younger artists, as well as to those of his own generation.

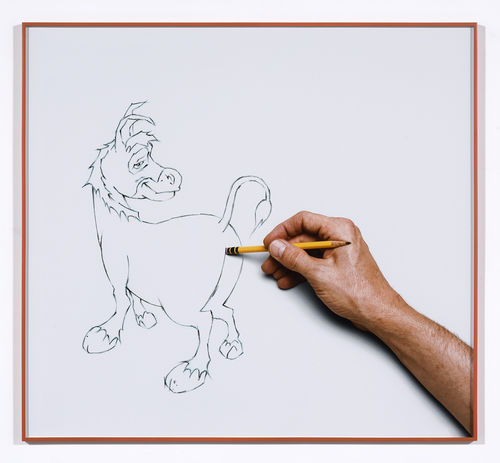

In 2007, Johnson once again began to make work. A series with animal themes combines an interest in the fetishistic "furry" or "plushy" culture with some of the tropes of early animation-the artist's hand visibly intervening and interacting with its creations. In Untitled (Giraffe) the artist's hand is again the hand of God, in a deliberate echo of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling. The artist gives life, but can also erase it. In Untitled (Ass), the obvious double entendre of the title is emphasized by the eraser end of the pencil entering the happy animal. "If art is the principal site/sight (both place and view) of being as emergence into connectedness," Leo Bersani has argued:

Then the metaphysical dimension of the aesthetic-which may also be its aesthetically distinguishing dimension-is an erosion of aesthetic form. Origination is designated by figures of its perhaps not taking place; the coming-to-be of relationality, which is our birth into being, can only be retroactively enacted, and it is enacted largely as a rubbing out of formal relations. Perhaps traditional associations of art with form-giving or form-revealing activities are at least partly a denial of such formal disappearance in art.26

Johnson literalizes "rubbing out" to mean the use of a pencil eraser. His subject "is produced from the outside in, then eliminated from the inside out." His Untitled (Kangaroo) (2007) reaches deep into a pouch that seems to offer access into the interior of one's own body. No doubt it is just a coincidence that Peter Lawford was arrested in an Australian gay bar in 1952, while filming the movie Kangaroo.

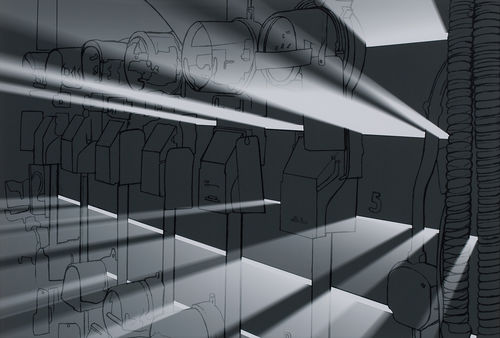

Another three works from 2007, Untitled (Meters), Untitled (Copier), and Untitled (Projector), form a sequence about light and the production of visual meaning. The meters regulate the power required, while at the same time obliquely referring to the role of light meters in photography. The photocopier produces images on demand, and the slide projector is used by teachers to impose meaning onto images. All the technology here is—once more—on the edge of obsolescence, as new forms of image manipulation continue to develop. A deeply shadowed, noir gloom envelops all three images, and the light that interrupts it does little to dispel the overall darkness. Where conventional iconography would posit a shaft of light as suggesting the revelation of truth or even religious enlightenment, the light in these works does not reveal much of anything. It leaks from the copier and flows arbitrarily through the slatted wall behind the meters. Only the light from the projector is focused, but we see nothing of what it shows. At the same time, it is hard to see these works as entirely cynical. Rooted as they are in the mundane means of production of meaning, some light still is shed.

In 2009 Johnson has made one more work, Untitled (Achievement: SW Corner, Glendale + Silverlake Blvds.). Based on something that Johnson happened to notice one day, it shows an Emmy sitting on an apartment windowsill. Like many of his works, it picks up elements from earlier pieces, in this case the line "I deserve an Oscar" from Untitled (The Two Economies) (1999-2000). Like all Johnson's stories, it is a fragment. We don't know who won this Emmy, or for what. We don't know whether the winner is a young hopeful on the way up or a former star clinging to his or her moment of glory. But the everyday setting suddenly touched by a hint of glamour is quintessentially Larry Johnson, quintessentially his Los Angeles. At any moment a Jaguar XKE is going to pull up. "How far you going?" the driver will ask. And the answer will be: "All the way."

Notes

1. Joan Didion, Where I Was From (New York: Knopf, 2003), 104.

2. Larry Johnson, "'American-ish Painting': Notes on Some Recent Works of Richard Hawkins" in Richard Hawkins (Cologne: Daniel Buchholz, 2003), 7.

3. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes from Johnson come from conversations on Jan. 21 and Feb. 7, 2009.

4. David Rimanelli, "Larry Johnson: Highlights of Concentrated Camp," Flash Art 23, no.155 (Nov.-Dec. 1990).

5. John A. Stormer. None Dare Call it Treason (Florissant, Mo.: Liberty Bell Press, 1964).

6. Norman and Betty Donaldson, How Did They Die (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980).

7. Gore Vidal, "Ronnie and Nancy: A Life in Pictures" (1983), in At Home (New York: Vintage, 1988), 78.

8. Gregg Tyler, The Joy of Hustling (New York: Manor Books, 1976). Tyler claimed to have donated his napkin collection to the Jackie Kennedy White House.

9. Joan Didion, "The White Album," in The White Album (New York: Washington Square Press, 1979), 16,17.

10. Frank O'Hara, "Ode to Causality," in Donald Allen, ed., The Collected Poems of Frank O'Hara (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 303.

11. Frank O'Hara, "The Sorrows of the Youngman: John Rechy's City of Night" (1963), in Standing Still and Walking in New York (Bolinas, Calif.: Grey Fox, 1975), 164.

12. Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1850; New York: Penguin. 1996), 11.

13. Didion, "The White Album," 47.

14. Luis Buñuel, My Last Sigh, trans. Abigail Israel (New York: Vintage, 1984), 41.

15. Ibid., 48.

16. Gerold Frank, Zsa Zsa Gabor: My Story (Cleveland: World, 1960); Patrick Dennis, Little Me (1961; New York Broadway, 2002).

17. Thomas Tryon, The Other (1971; Lakewood, Colorado: Centipede, 2008).

18. Joan Didion, "The White Album," 46.

19. Larry Johnson, "Tim and Sue's Excellent Adventure," in Tim Noble and Sue Webster (Los Angeles: Gagosian, 2001), 15.

20. Andrew Ross, No Respect: Intellectuals and Popular Culture (London: Routledge, 1989), 139.

21. Dave Hickey, "Larry Johnson's malicious muzak," Frieze (Jan.-Feb. 1994): 31.

22. Gary Indiana, "Gags," in Larry Johnson (Vancouver: Belkin Art Gallery, 1996), 51-52.

23. Guy Debord, Panegyric, vol. 1 (1989), trans. James Brook (London, Verso. 2004), 34.

24. John Rechy, City of Night (New York: Grove, 1963), 9.

25. Joe Sola, e-mail to the author, Jan. 10, 2009.

26. Leo Bersani, "Sociality and Sexuality," Critical Inquiry 26, no. 4 (Summer 2000): 641-656.

The catalogue is published with the assistance of The Getty Foundation.