Hammer Projects: Christopher Russell

- – This is a past exhibition

Steeped in historical references, Russell’s novella Budget Decadence seamlessly fuses writing and object making to create an all-encompassing environment that challenges the traditional divide between the two practices and expands the very idea of what a book is. To stand in his Hammer Project installation is to stand, literally, in the novella.

Heavy with the psychological implications of home, interior, and family, the story unfolds, inspired by decadent writers of the late nineteenth century, rich in often unsettling details that build toward catastrophe. Simultaneously, Russell refreshes for our millennium the experiments in poetic strategies applied to prose by the New Narrative writers of the 1970s and 1980s, adding layers of meaning and possible interpretation.

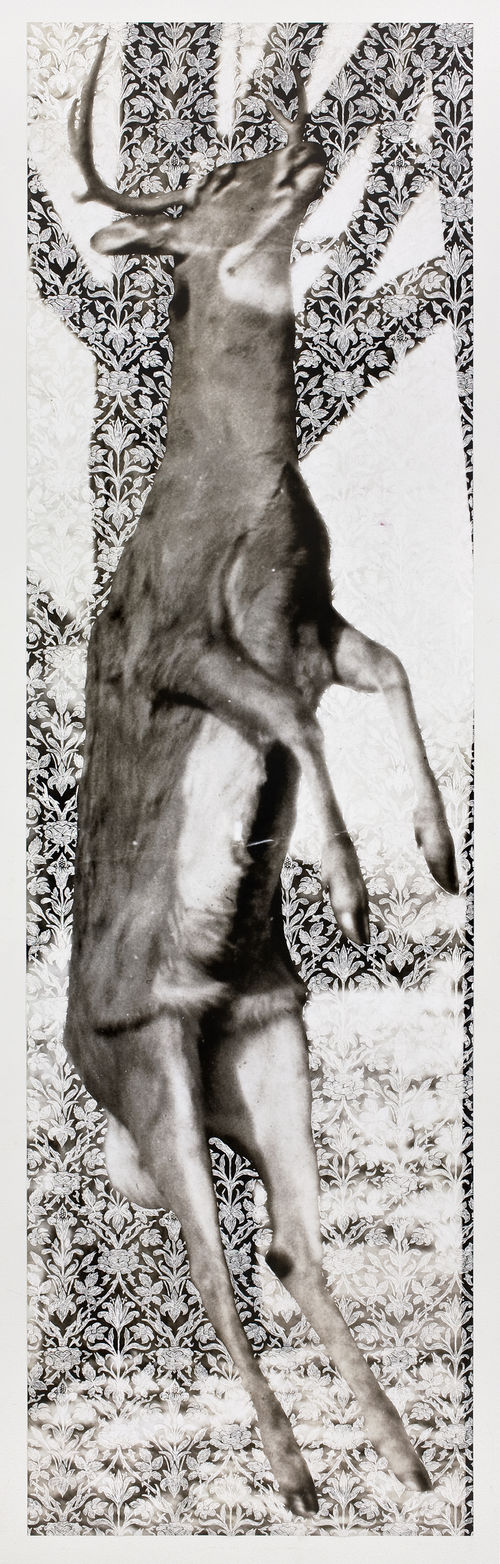

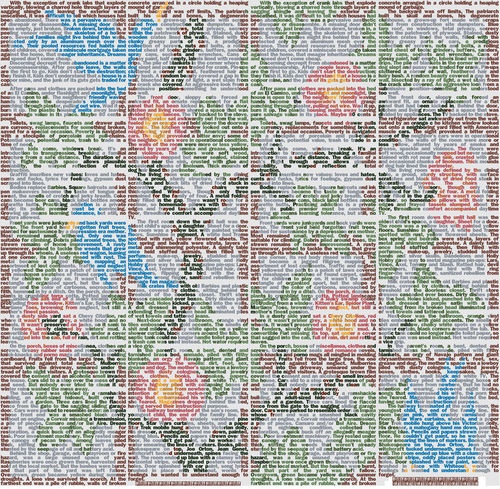

Jarring juxtapositions and stark imbalances are apparent in much of Russell’s work: the photographic images and his treatment of their surfaces, his choice of framing materials and furnishings for the gallery, his digital mimicry of Arts and Crafts movement progenitor William Morris’s Trellis wallpaper (the first chapter of Budget Decadence), and his hybrid artist books/zines (each containing subsequent chapters of the novella). Nevertheless, the seemingly disparate aesthetic elements of the installation are in fact deliberately chosen and constructed as reiterations of themes in the text.

Curated by Darin Klein.

Biography

Los Angeles–based artist and writer Christopher Russell received his BFA from California College of the Arts and Crafts in San Francisco in 1998 and his MFA from Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California, in 2004. From 2001 to 2005 Russell edited, designed, produced, and distributed the “destroy-to-enjoy” literary art zine Bedwetter. He has exhibited his work at Acuna Hansen, Los Angeles; White Columns, New York; Van Harrison Gallery (Gallery 1R), Chicago; and other venues. Landscape, a monograph on his work, was published in 2007 by Kolapsomal Press. Russell edited and wrote an essay for the catalog that accompanied his curatorial debut, Against the Grain at Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions in 2008. Additionally, he has written more than two dozen articles and reviews about art in Los Angeles. A version of this installation will appear in book form later this spring through 2nd Cannons Publications. Russell’s work is in various public collections, including the Getty Research Institute; New York University; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. This is his first solo museum exhibition.

Essay

By Amy Gerstler

I became convinced that buildings don’t just fall into ruin—something in them aspires to ruination. It’s the same with people.1

Christopher Russell creates “ripe ruins.”2 His artworks can be seen as portraits in absentia: of individuals and families who’ve fallen through the cracks, and of their ailing environments. “I photograph the physical margins of the social pact,” he has said, “the edges of town, spaces that have been . . . abandoned.”3 Employing “intermingled layers of narrative and images,”4 and materials such as floral fabrics, glitter, dirt, and hacked and scratched photographs, Russell gives us sun-bleached, ripped, splattered, graffitied, murky, erotic, sullied, elegant evidence of resilience and destruction.

In his untitled installation for the Hammer Museum, as in much of his work, Russell’s human subjects have died off, fled, or been removed. We are left with their detritus: furnishings, stained bedspreads, scribbled notes, smears, empty rooms, and interior monologues that surface in tiny, eye-testing type emanating from the wallpaper. “I’m trying to look at this white trash residence the same way that Huysmans is looking at his environment,” he comments in discussing the piece.5 The novels of French writer J. K. Huysmans (1848–1907) are known for lush description, strange images, obsession with decadence and decay, and litanies of darkly realistic detail.

Russell identifies with the tradition of street photography, as carried on by artists like Lee Friedlander. Expanded beyond the practices of those predecessors, Russell’s work contains not only reportage but also deliberately cultivated elements of imagination. He employs techniques of both fiction and nonfiction: “I consider myself a street photographer, even though my fiction writing, drawing, and installation seem at odds within a documentary genre. I record observed moments. However, I am not invested in strict reportage. Instead, I create installations of photographs, digital imagery, and fictional texts that make use of narratives developed while wandering. . . . Photography provides a foundation for the numerous activities that comprise my practice.”6

In talking about parallels between street photography and French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s (1821–67) habit of trolling the alleys of Paris to gather startling details for his writing, Russell notes, “He was wandering and looking too, and it’s sort of weird to think that that applies when looking at domesticity but it’s the same sort of detached wandering room to room that I do in this piece, the same as wandering the streets of Paris, taking things in and looking at them in this real detached way.”7 As he has said, “Central to my work as a whole is a fond reassessment of what street photography might become.”8

Russell, then, is chronicler, generator, and embellisher, distanced conduit of suppressed or lost narratives. He gains omniscient admittance to his subjects’ dwellings and consciousness via an admixture of acute observation and fictionalizing. He moves beyond facades and street scenes that his artist forebears documented, slipping indoors, sliding inside his characters/inhabitants through use of the interplay between visual and written images. Writer Italo Calvino, in an essay titled “Visibility,” observes, “We may distinguish between two types of imaginative process: the one that starts with the word and arrives at the visual image, and the one that starts with the visual image and arrives at its verbal expression.”9 Russell’s piece at the Hammer, it seems to me, is situated where those two types of imagination interact. Indoors and outdoors encroach on each other’s territory in this work, as nature moves to repossess what we’ve tried to wall off, to safeguard from her ravenous advances our fragile stabs at being “family,” our failed attempts to be tidy, loving, unified, civilized. Inside and outside, what we wanted to protect and what we wished to be protected from begin to leak together. They start to overwrite or colonize each other: “Thus the two spaces of inside and outside exchange their dizziness. . . . Outside and inside are both intimate—they are always ready to be reversed, to exchange their hostility.”10 In the process, some of the hidden is revealed, or at least partly exposed to our nosy gaze.

One specific manifestation of the interpenetration of indoors and outdoors, inside and outside in Russell’s work is that decor and decay often merge or trade places. Many of his photographs are either of places that are trashed and falling apart, and/or they are themselves, as photographs, stained, dirty, damaged, hurt. Here decay becomes its own kind of decor that creeps in where humans have abandoned their habitats. Decay then begins tinkering with and partially replacing what decor remains. When this happens, an unsettling mental and physical place of boundary breakdown is created. As the literary philosopher Gaston Bachelard has written, “In this ambiguous space, the mind has lost its geometrical homeland and the spirit is drifting.”11

Adverse circumstances maimed a neighborhood in the narrative that informs Russell’s work at the Hammer. Here are the opening sentences of a text that appears on wallpaper in the installation, printed using a ghosted-in antique floral pattern: “With the exception of crank labs that explode vertically, blowing a charred hole through layers of sagging shingle and leaving the exterior walls unscathed, it was difficult to tell which houses had been abandoned. There was a pervasive aesthetic of disrepair.” What passed for “family” similarly eroded the four characters evoked in the installation. Our job is to examine the debris Russell has assembled, reconstructing something of the what, who, when, and the how did it happen here as we wander through the backwash of toxic domesticity he’s created. It’s difficult to stroll through this piece without musing about how similar familial, social, and economic forces may also be consuming us. Writer Geoff Dyer, in an essay on the urban wreckage of Detroit, remarks, “Ruins don’t make you think of the past, they direct you toward the future.” In the case of Russell’s constructed, realistic/fanciful ruins, they put this viewer in mind of both what has been and what may be to come. Dyer continues: “The effect is almost prophetic. This is what the future will end up like. This is what the future has always ended up looking like.”12

Notes

1. Geoff Dyer, “The Rain Inside,” in Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It (New York: Pantheon Books/Random House, 2003), 227.

2. This phrase from photographer, writer, and documentarian Camilo Jose Vergara is quoted by Geoff Dyer (ibid., 220–21). Vergara’s work has interesting links to Russell’s, a topic that there is not enough room to discuss here. What follows is a capsule description of one relevant project Vergara dreamed up: “Vergara proposed that 12 square blocks of crumbling downtown Detroit be declared a ‘skyscraper ruins park,’ an ‘American acropolis,’ for the preservation and study of the deteriorating and empty skyscrapers. ‘We could transform the nearly 100 troubled buildings into a grand national historic park of play and wonder, an urban Monument Valley. . . . Midwestern prairie would be allowed to invade from the north. Trees, vines, and wildflowers would grow on roofs and out of windows; goats and wild animals—squirrels, possum, bats, owls, ravens, snakes and insects—would live in the empty behemoths, adding their calls, hoots and screeches to the smell of rotten leaves and animal droppings.’(Metropolis, April 1995),” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camilo_Jos%C3%A9_Vergara.

3. Christopher Russell, unpublished artist’s statement, 2008.

4. Ibid.

5. Christopher Russell, interview with the author, 2008.

6. Russell, unpublished artist’s statement, 2008.

7. Russell, interview with the author, 2008.

8. Russell, unpublished artist’s statement, 2008.

9. Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the Next Millennium (New York: Vintage International, 1988), 83.

10. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 217–18.

11. Ibid., 218.

12. Dyer, “The Rain Inside,” 219.

Amy Gerstler’s most recent book of poetry is Ghost Girl (2004). Her work has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, including the New Yorker, Paris Review, American Poetry Review, and The Norton Anthology of Postmodern American Poetry. Her art writing has appeared in Artforum and other magazines and in exhibition catalogs for various museums.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay-Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund, and Fox Entertainment Group’s Arts Development Fee. Gallery brochures are underwritten in part by the Pasadena Art Alliance.