Oranges and Sardines

- – This is a past exhibition

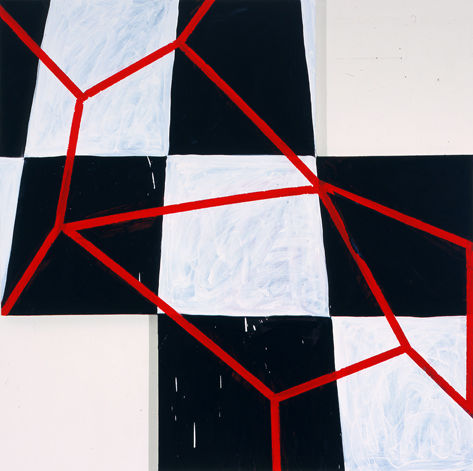

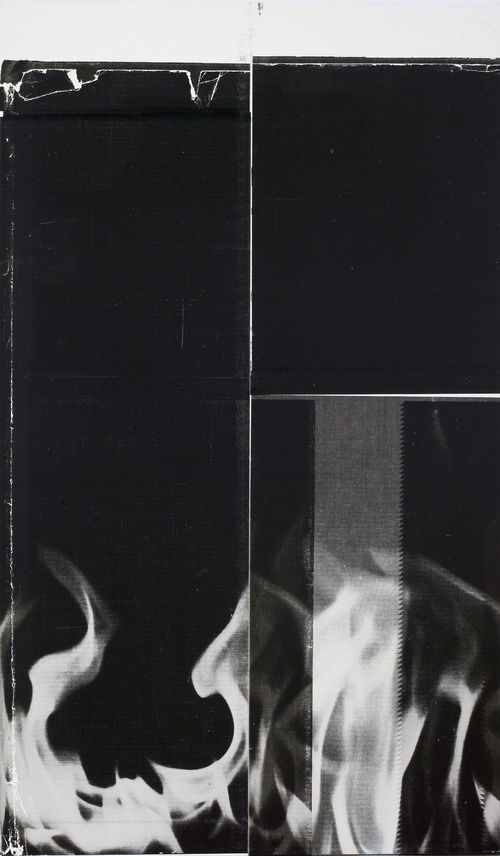

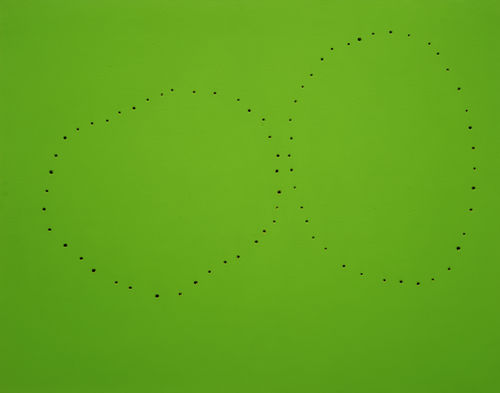

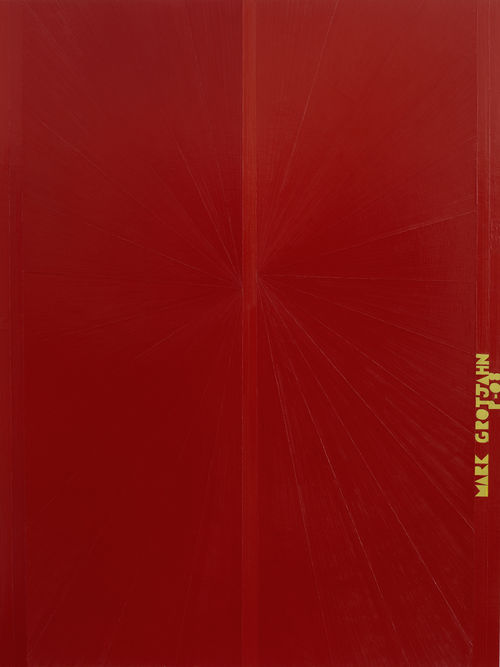

Oranges and Sardines examines how art can illuminate art, exploring the impact of approaching art through the eyes and minds of artists. Six contemporary abstract painters—Mark Grotjahn, Wade Guyton, Mary Heilmann, Amy Sillman, Charline von Heyl, and Christopher Wool—select one of their own recent paintings as well as works by other artists who have been significant in their thinking about their work. Six separate and generous galleries present their choices in a constellation of diverse works including Paul Klee, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Francis Bacon, David Hockney, Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Evan Hesse, Pablo Picasso, and Dieter Roth, and artists less well-known to the public. The artists' choices have developed through many conversations with curator Gary Garrels about the issues of their work, their studio processes, their appraisals of art history, and the status of contemporary art. Throughout this process, a distinct distillation of choices has developed for each artists that is wide ranging but specific—works that are figurative as well as abstract have been chosen, sculptures and some works on paper have been selected in addition to painting; and historical as well as more contemporary works are juxtaposed. Shown together, these works engage in a visual "conversation" with each other, provoking fresh insights into artists who are well-known and opening consideration of artists that may be more obscure.

Organized by Gary Garrels, chief curator.

Catalogue

Oranges and Sardines will be accompanied by a catalogue that will include an introductory essay by the curator and extended interviews with each of the artists. All the works in the exhibition will be reproduced in full-page color, and additional works will be reproduced in tandem with artists’ interviews.

Essay

By Gary Garrels

This exhibition approaches art through the eyes and minds of artists. As a curator I have found that artists look at art with a focus and scrutiny, a criticality and level of engagement that few of us are able to summon with the same intensity. Working with the six artists who have made this exhibition with me, I have been struck more than ever by the particularity of artists’ visions. The general does not suffice; the specific matters intensely—a selection of subject, a choice of material or color, a way of making a mark or placing a gesture onto a canvas, a determination of the appropriate scale of an object (and larger does not necessarily mean better or more important). Artists also acknowledge the importance of how and when a work of art was first encountered, that the circumstances of seeing and experiencing a work of art may be as important as the object itself. As well artists are singularly aware of how fundamentally a work of art is joined to the life of its creator, that within these objects are embedded experiences that may forever be unknown to the outside observer. Yet these experiences are crucial to how and why an object was made and to the final visual presence of the object.

This exhibition is a testament to the persistence of the visual art object and particularly abstract painting. It is a reckoning with an abiding question: what is the necessity of a work of art? Abstract painting amplifies this question a hundredfold. What is the claim of abstract painting to our attention, to our lives? Why should it continue to persist a century after its emergence?

Six contemporary abstract painters each have been asked to select one or two of their own recent paintings to be shown with works by other artists who have had a significant impact on their thinking and the development of their own work. The artists' choices were winnowed through many conversations I had with each of them, discussing the issues of their work, their studio practice, their appraisal of art history, and the contemporary situation of art. Throughout this process a distinct distillation of choices developed for each artist that is wide ranging but particular: both figurative and abstract works have been chosen, sculptures and some works on paper have been selected in addition to paintings, and historical as well as more contemporary works have been juxtaposed. Each artist has been given a generous gallery in which to present these works, and the choices were made in part to engage in a visual “conversation,” to form a constellation of objects that could reflect back and forth onto one another.

I chose these six artists because I admire both the objects they make and the character of their thinking. They were selected not as the only artists of distinction making abstract painting today, but as exemplary, representing the range and complexity, the vitality and potential of abstract painting today. They all are American, and as much as anything that is due to proximity, the possibility to engage in repeated and extended conversations.

The title for the exhibition is taken from American poet Frank O'Hara's poem “Why I Am Not a Painter,” which reflects on the elusiveness of the creative process, often resulting in a finished work that bears no resemblance or immediate relationship to its initial inspiration. O'Hara was not only a poet but also a curator and critic who grounded his critical approach to art not in theory or philosophy, but in a distinct appraisal of the artworks themselves, the cultural situation of the time, and the circumstances of the artists. That approach is reflected in this exhibition.

Abstract art emerged about one hundred years ago, specifically in painting, and through a shift away from representation.1 Yet what is encompassed by the term abstract has long been questioned and never tightly defined. Briony Fer has written: “As a label, the term ‘abstract’ . . . covers a diversity of art and different historical moments that really hold nothing in common except a refusal to figure objects.”2 By pushing away from external reference, abstraction enabled artists to explore a wide variety of visual expression. They were able to more fully engage subjectivity, emotional expression, decorative embellishment, complex metaphors, spiritual connection, and philosophical inquiry. Yet shortly after abstract painting developed, artists and writers began to challenge the continued meaning and relevance of painting of any variety and of art altogether. The Russian avant-garde artist Alexander Rodchenko made monochrome paintings in 1921 and declared them the last paintings. Ad Reinhardt made a comparable claim in the 1960s with his black paintings.3 In the 1960s arguments by both artists and critics appeared to leave little room for painting. One of the most closely and elegantly argued considerations of painting’s relevance or lack thereof has been made by Yve-Alain Bois in his book Painting as Model. Near the end of that book, he writes: “Yet has the end come? To say no . . . is undoubtedly an act of denial, for it has never been more evident that most paintings that one sees have abandoned the task that historically belonged to modern painting (that, precisely, of working through the end of painting) and are simply artifacts created for the market and by the market (absolutely interchangeable artifacts created by interchangeable producers).” And he then goes on to add, “As observed by Robert Musil fifty years ago, if some painting is still to come, if painters are still to come, they will not come from where we expect them to.”4 The unanswered questions are: Where would painters come from if they were to have relevance? And why would they be relevant?

So I have gone to painters, the culprits, to consider these questions. Why would anyone commit his or her life to making paintings? Surely many, if not most, artists do not believe that they are making works primarily in order to sell them. So what is it that inspires artists to make art, specifically paintings, and more specifically abstract paintings? The idea that some inner necessity compels them to do this work remains essential. But then what makes the difference between works that claim our attention and those that do not? I would say that complexity and ambition are salient. The difficulty of making new work in the face of all the art that has come before is a challenge that must be reckoned with. Many artists have a deep knowledge of art and art history and of the intellectual arguments around art, the theory and philosophy that attempt to provide more secure underpinnings to an understanding and appreciation of art. (But of course for some artists these issues are of relatively little concern.) Still artists generally do not make their work to fit within a framework constructed by art historians, theorists, or philosophers. Russell Ferguson, in his consideration of Frank O'Hara, observed: “The real lives of artists, and their relationships with those they consider their peers, are much more complex than the processes of art history sometimes reveal them.”5 Kirk Varnedoe, in his prolonged and thoughtful consideration of abstract art, made a parallel observation: “Epochs do not have essences, history does not work by all governing unities, and works of art in their quirkiness tend to resist generalities.”6

Artists feed on art to nourish themselves. What became ever clearer to me in organizing this exhibition was that I could never second-guess the artists in terms of what works of art they would focus on. They often were interested in artists whom many others might consider obscure or in works by better-known artists that might be seen as idiosyncratic. But canonical masterpieces were often as inspiring to them as to any art historian, or curator, or member of the general public. These artists revealed to me more than ever that painting in general and abstract painting in particular, rather than being exhausted by what has come before, can in fact be nurtured by the astonishing array of references now available. The potential sources of inspiration are myriad, perhaps unfathomable. The complexity, density, and diversity of art give ample reason to understand why abstract painting has not dried up or withered away.

In an informal lecture given many years ago, the abstract painter Robert Ryman remarked that abstraction is such a relatively young form of art that it was impossible for him to fathom how anyone could suggest that it might be exhausted. To him the far more likely situation was that abstraction was still in an early phase, that its future could hardly be imagined, that its potential might not be realized for decades to come.7 Varnedoe reinforced this view when he wrote, “Abstract art has been with us in one form or another for almost a century now, and has proved to be not only a long-standing crux of cultural debate, but a self-renewing, vital tradition of creativity.” He continues: “This is one of abstraction’s singular qualities, the form of enrichment and alteration of experience denied to the fixed mimesis of known things.”8

Abstract painting is in many ways anathema to the society and culture in which we live. Mass media, electronic communication, and a deluge of information envelop us. The competition for our attention is ever more relentless, our attention spans ever shorter. Abstract painting, by contrast, reveals itself only through sustained attention and close observation.9 Abstract painting, like all art, remains tied to lived experience. Reproductions will always fall short of the work itself. There is no description that is commensurate to one’s own relationship with the work.

Within experience, many factors come into play—observation but also perception, emotion, and thought. Art offers the invitation to engage experiences filtered through the artists' experiences—an accretion of memories, relationships, thoughts, and feelings. Painting as a physical phenomenon retains linkages to material existence, to the visceral, obdurate, and fragile character of life. It reflects the body and mind, tied up into one indivisible knot. It offers an experience that in turn inflects experience, deepening and enriching our ability to reckon with who we are and where we have been. Like life, art refuses to be categorized, summarized, solved, and closed. It remains difficult to adequately describe and to evaluate. Relative merits may be argued, but finally meaning and value are tied to the particular individual. Who is to say how long abstract painting—or any painting—will remain relevant to our lives? But for now it is clear that abstract painting remains vital for those who make these works and for an audience that savors the experiences that these artists offer us.

Notes

1. See Mark Rosenthal, Abstraction in the Twentieth Century: Total Risk, Freedom, Discipline (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996).

2. Briony Fer, On Abstract Art (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000), 5.

3. For a vivid account of these positions, see Jodi Hauptman, “Imagination without Strings,” in Drawing from the Modern, 1880-1945 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), 13-14.

4. Yve-Alain Bois, Painting as Model (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993), 241, 244.

5. Russell Ferguson, In Memory of My Feelings: Frank O'Hara and American Art (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art; Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), 16.

6. Kirk Varnedoe, Pictures of Nothing: Abstract Art since Pollock (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006), 7.

7. Talk given on January 9, 1991, in New York as part of the Guggenheim Museum’s Salon Series and subsequently published as “Robert Ryman: On Painting,” in Robert Ryman (Schaffhausen, Germany: Hallen für neue Kunst, 1991), 67.

8. Varnedoe, Pictures of Nothing, 29, 34.

9. See Richard Shiff, “Force of Myself Looking,” in Plane Image: A Brice Marden Retrospective (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), 29-66.

Major support for the exhibition is provided by The Joy and Jerry Monkarsh Family Foundation.

It is also made possible by Susan and Larry Marx, Brenda R. Potter, David Teiger, The Broad Art Foundation, Susan Bay-Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy, The Straus Family Fund, and Herta and Paul Amir.

Additional support is generously provided by the Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation.