Houseguest: Jennifer Bornstein

- – This is a past exhibition

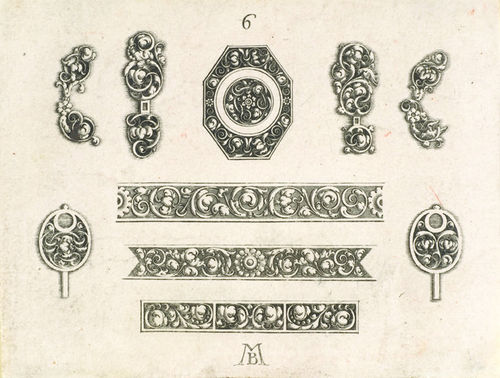

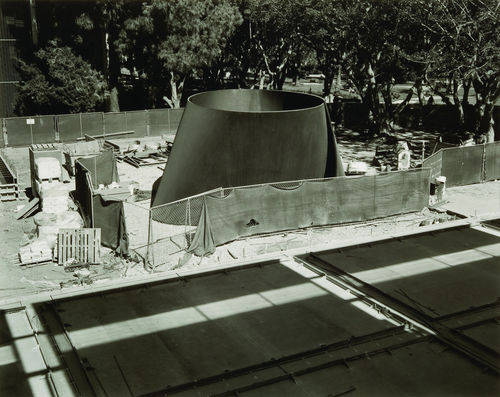

The Hammer introduces Houseguest, an occasional series in which we invite an artist to study the collections first-hand and curate an exhibition from our holdings. For the first of this series, Los Angeles-based artist Jennifer Bornstein visited the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts over a period of six months. She browsed through a historical landscape of works on paper, and selected prints, drawings, and photographs by artists as diverse as Rembrandt van Rijn and Man Ray.

Curator Biography

Jennifer Bornstein was born in Seattle and lives in Los Angeles. She received her BA from UC Berkeley in 1992, and her MFA from UCLA in 1996. Bornstein has had solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Greengrassi, London; Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York; Blum and Poe, Los Angeles; and Studio Guenzani, Milan. Group exhibitions of her work include the 2nd Moscow Biennale; the Biennale d’art contemporain in Le Havre, France; and exhibitions at the ICA, London and the CCA Wattis Institute, San Francisco.

Essay

By Jennifer Bornstein

We are all collectors of things, whether we know it or not; it’s the definition of thing that varies. Some of the things that I collect are books, words, handwritten letters, and disposable works on paper (what others might call trash). I’m possessive only about the books. With few exceptions, I don’t like it when people browse through my books. For some reason, nearly everyone who visits my apartment seems to browse through my books, and some even ask to borrow them. I do lend books because I believe that they should be used, but it’s usually with regret. There are several reasons why I want my books to be left alone, but the main one is that they always become disorganized when people pull them out. I know that the shelves must appear haphazard, but there’s actually a logic in place. Some people organize their books according to author or subject; I organize mine according to sunlight. That is to say, the books are kept on a shelf that runs along a wall in my apartment. The right side of the shelf faces a window and receives some sunlight; this is where I keep books that are expendable, like novels and biographies. The left side of the shelf, especially the area near the floor, stays dark. This is where I keep the books that are most treasured to me.

As a collector I also take pleasure in seeing what others collect and how their collections are organized. It particularly interests me to see how ephemera like notes, proofs, or casual sketches can transition from throwaway status to valued objects, with sentimental or monetary value imparted to them. I’m as interested in collections themselves as in why things have been collected, how they are grouped together, and the narratives that result. The narratives woven around objects often have nothing to do with the objects themselves. They are narratives about the possessor, are often intimate, and are attached to experiences that are not tactile. Their generation reveals the ability of objects to function as souvenirs of authentic experience.

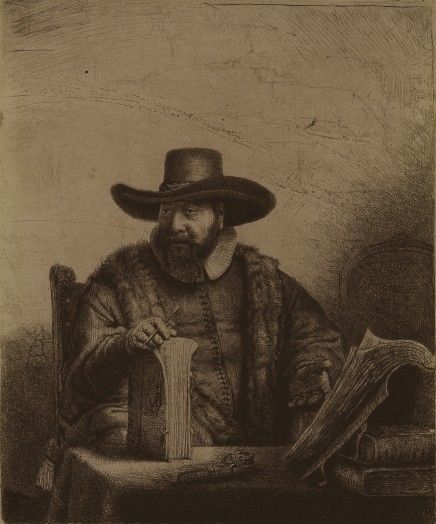

For all these reasons it was a true pleasure to have been invited to curate this exhibition from the Grunwald Center’s extraordinary collection of works on paper. Taking as my point of departure Walter Benjamin’s premise that the fruits of wandering can be more productive than those of labor, for five months I meandered through the Grunwald collection, not so much curator as flaneur. The works I’ve selected for this exhibition are gathered together accordingly. They have been chosen following a logic that grows from reverie, taking advantage of the Grunwald as a melting pot where old masters and the creations of hobbyists can mix with equal importance. The starting point for the exhibition was Rembrandt van Rijn. From there I burrowed through to Francisco de Goya, Philip Guston, Katherine Diehl, Barbara Morgan, Lewis Baltz, Sister Corita Kent, Mel Bochner, Dennis Cooper, and James Welling. This list of artists is a map of my influences and interests, and of the worm trail I made through the collection.

To handle these works at the Grunwald (where they are stored as pieces of paper—in storage boxes, unframed, with a general air of inaccessibility that seems intended to eliminate the chance of contagion) was an unexpectedly intimate experience, almost like meeting the artists in person. Some are works that I admired in reproduction as a teenager, created fantasies about, and imbued with impossible attributes of perfection—for example, Diane Arbus’s A Castle in Disneyland, California. Much like seeing a crush or a celebrity appear next to you in real life, to find this work at the Grunwald evoked sensations both of Freud’s uncanny and of the cliché. Stumbling across it in person was an equally foreign and familiar experience and, consequently, disconcertingly strange. It was equally startling to handle the unframed Rembrandt etchings. Five hundred years after these etchings were made, Rembrandt’s technique remains stunning. I could not help wondering if the artist himself had touched the pieces of paper sitting in front of me.

After studying some works for so many years in reproduction, seeing them in person made me readjust my perception of them. Some looked too big and almost garish in real life: for example, the David Hockney lithograph of Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, which I had previously only seen reproduced at a Lilliputian scale. In real life it appeared enormous and slightly grotesque. The scale of Adolph Gottlieb’s beautifully curious drawing on a sheet of notebook paper, Portrait of Marcus Rothkowitz (Mark Rothko), makes more sense to me. Other works resonated as curiosities. I had no idea that Man Ray made lithographs, let alone colorful abstract lithographs such as Composition. (An art historian wrote that Man Ray probably made this undated print while living in Los Angeles in the late 1940s.) I chose Anders Zorn’s etching of Paul Verlaine because I love Paul Verlaine, and I understand the need to make an etching of an author one admires; I chose the work by Kiki Smith, Untitled (Self-Portrait), because it reminds me of a photograph by Rudolf Schwarzkogler. What is Smith doing in that photograph?

But of all the works that I discovered in the Grunwald collection, the one that is most significant to me is Location Piece #2, New York City–Seattle, WA, July 1969, Douglas Huebler’s portfolio of offset photolithographs with accompanying maps and text. It is Huebler’s work that inspired me to make photographs, and it’s his fault that I never bothered to learn technique. The images in this portfolio are intended to be anonymous, but they resonate with a Proustian significance for me, as I clearly recognize many of them as images of a park near the house where I grew up. I have an intimate relationship with this park. I spent many afternoons there with my mother as a child, and often loitered there as a teenager. Looking at this portfolio, I again have the uncanny feeling that I am meeting an artist who has been the object of my admiration for many years. In this case, however, I am reminded that I actually did meet Huebler once, in 1995. It is a meeting that sticks in my mind because it was so eagerly anticipated by me, and also so laboriously arranged. I was a graduate student at UCLA at the time and was in charge of arranging artists’ lectures at the school. A huge fan of Huebler’s work, I had him at the top of my wish list. After several long telephone calls to his home in Massachusetts, during which I flat-footedly tried to convince him to visit, I finally got him to agree, and in September 1995 I triumphantly had him on the roster. I sent him the school’s standard package of materials with information about the stipend. One week later I received the following letter, handwritten on a piece of typing paper (which of course I still have):

9-24-95

Dear Jennifer Bornstein,

This is written confirmation that I must rescind my agreement, (by telephone), to give a talk at UCLA on Oct. 16. I left a message on your answering machine but did not want to back out that way, therefore this note.

When I was Dean at CalArts I worked hard to provide more money for the honoraria offered to visiting artists (and to insure that all offers were the same amount). I certainly do not believe that you should take the heat on this matter, but in today’s market $150 is not adequate for preparation of material, and actual presentation time. (I was asked to make a second lecture after speaking with you for substantially more and refused because I did not feel that I had the time.) As I said, I should have confirmed the honorarium before finishing our telephone conversation but because UCLA had paid my airfare and a $400 or $500 honorarium 20 years ago I assumed a reasonable fee for my services based on that--!

Regretfully,

Douglas Huebler

I had no good response for this—he was right. So I bullheadedly demanded an audience with the chair of the art department, recounted the story, and requested that the stipend be raised. Surprisingly, after much discussion the chair agreed, and the stipend for visiting artists was permanently raised to $500. Huebler was the first person I called to tell the news. I invited him again to visit. He must have been more impressed by my tenacity than by the paycheck, because he accepted the invitation. In retrospect this seems like an extraordinarily kind gesture on his part. I remember that he gave a wonderful lecture. Afterward I asked him to sign my copy of Douglas Huebler—Variable, Etc. (As a student I thought this was an enormously extravagant book purchase. Looking at it now, I see the price written in pencil inside the front cover: $25.) On the title page he wrote: “For Jenny. It’s a pleasure to meet you! Douglas Huebler.” That book is now on the darkest, lowest, leftmost corner of my bookshelf.

Jennifer Bornstein is a guest curator.