Hammer Projects: Erin Cosgrove

- – This is a past exhibition

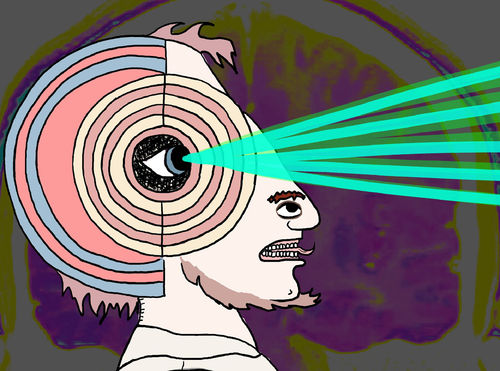

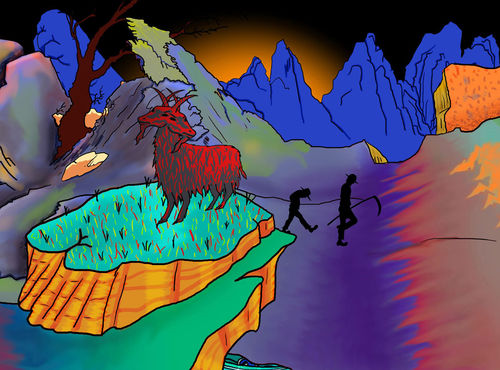

Erin Cosgrove’s epic animation, What Manner of Person Art Thou? (2008), follows Yoder and Troyer, the only survivors of two small Amish-like colonies in the Northwestern U.S., after a series of catastrophes and epidemics. The two set off on a journey to find any remaining relatives and begin dispensing violent justice on the evildoers of contemporary society; each encounter represents one of the seven deadly sins. The striking visuals are inspired by the 11th century Bayeux Tapestry. The video is a darkly funny tale of the corruption of modern life and the hazards of morality. Cosgrove lives and works in Los Angeles and this is her first solo museum exhibition.

Organized by Ali Subotnick, curator.

Screening Times

Tue, Wed, Fri, Sat

11:00, 12:10, 1:20, 2:30, 3:40, 4:50, 6:00, 7:10

Thurs

11:00, 12:10, 1:20, 2:30, 3:40, 4:50, 6:00, 7:10, 8:20

Sun

11:00, 12:10, 1:20, 2:30, 3:40

Biography

Erin Cosgrove was born in 1969 and lives in Los Angeles. She received her BFA from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, in 1996, and her MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 2001. Cosgrove has had solo exhibitions at the Espace Croisé Centre d’Art Contemporain, Roubaix, France; Carl Berg Gallery, Los Angeles; and Printed Matter Inc., New York. Group exhibitions of her work include the COLA Fellowship Exhibition, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery; City Beat: Internet Video Exhibition, Brooklyn Museum; and Los Angeles Art Now, Galleri S.E. International Contemporary Art, Bergen, Norway. In 2008 she received the Creative Capital Film and Video Grant and the Center for Cultural Innovation Investing in Artists Grant, and in 2004 she was awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship. In 2003 Sundance Channel’s TVLab produced her seven-minute animation and live-action video, A Heart Lies Beneath, and that year her novel, The Baader-Meinhof Affair, was published by Printed Matter, Inc., New York.

Essay

By Julian Gough

I yearn for sex, and food, and status, yet when I get all these things, I want more. There must be some greater thing that would satisfy all yearning forever...

People have come up with many ideas to satisfy this human ache. Most have been called religions and involve stories designed to make you feel better (you are not a serf, you are the beloved son of God).

Religious stories have grown less effective as the advancing tide of science has washed away their foundations. Yet the stories science tells don’t satisfy our needs. So the various arts—once humble servants of religion—have been promoted. Art museums are the cathedrals of our time. Neoconceptualism has taken over the role of Jesuitical Catholicism: intricate, elitist, conceptual, and aping the intellectual rigor of science without actually achieving it.

But the masses never cared for ideas, concepts. The masses went to mass for a regular, often violent story that ultimately reassured. That need for a regular, weekly comforting fable of redemption is met today by the popular art forms: romance novels, soap operas, Oprah, cartoons. That transition, from religion to secular modernity, opens up a huge cultural space. This is the space in which Erin Cosgrove operates. And with What Manner of Person Art Thou? (2004–2008), she takes on animation, because the cartoon—pure art, free to do anything at all—most clearly reveals our needs.

The new art-religion of animation went from revelation, to orthodoxy, to stagnation, to reformation at appropriately cartoon speed. Walt Disney, watching rushes of a live-action movie, once asked casually, “What f-stop was used in that shot?” When told it was 5.6, Disney remarked, “I like that. Enough is in focus, but not too much, it’s just right.” From then on, as Walter Murch says, “every film at Disney Studios had to have the exteriors shot at an f-stop of 5.6. . . . Even the most accidental comment was the word of God.”1

Cosgrove, like Warhol and Lichtenstein before her, sees that the vigor of popular art comes from somewhere deep and that high art needs low art’s splendid energy. She also realizes that religious art only appeared to disappear. From Cinderella to The Lion King, Disney gave us the same story of suffering and redemption—of the orphan who turns out to be heir to the throne—again and again. It is the story of Christ.

If Disney is Christianity, then The Simpsons is the Enlightenment. (And Matt Groening is Voltaire.) Only with The Simpsons was there an alternative American vision of animation strong enough to stand up to Disney’s, in the full flow of the mainstream.

But Erin Cosgrove is a heretic, whose work critiques both Disney and The Simpsons. For her, animation, like salvation, is direct, personal, and deeply felt. She skewers the sentimental lies of Disney, but even more bravely in an American liberal arts context, she points out the fatal flaw in The Simpsons’ Enlightenment project. Because The Simpsons, brilliant as it was in the early seasons (and still is, in flashes), has never acknowledged death. And death is the only American subject. Disney, from Bambi to The Lion King, was at its best when it acknowledged death. The Simpsons (brilliantly!) represses death, crushing it into the tight box of The Itchy & Scratchy Show. But the Simpsons themselves, like all sitcom families, are trapped in a happy moment to which they are doomed to return at the end of each episode. Life in a sitcom is endless reincarnation without punishment or reward, without learning or growing. In this, the Simpsons reflect America.

Cosgrove has always tried to show us just how much darkness is being hidden behind these comforting, industrially produced stories. Her genius is for comparing the frothy and the heavy (the romance novel and the terrorist manifesto, the cartoon and the Bible), and showing their identical yearning for a big story that will make sense of the universe. Or, as the heroine of Cosgrove’s A Heart Lies Beneath (2004) says thoughtfully, after listening to the student terrorist followers of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, “You guys are kind of like Trekkies.”

Umberto Eco has spoken of the return of the Middle Ages: of modern gated communities as medieval walled towns. In What Manner of Person Art Thou? Cosgrove makes the return of the Middle Ages literal. By an elegant device—disease ravages an isolated fundamentalist community that has utterly rejected modernity—she releases two survivors of the Middle Ages into modern America. Elijah and Enoch’s ferocious, unironic version of reality collides again and again with our mediated, ironized version. There is blood. Blood, and irony.

One expects jokes at the expense of an old religion that has lost its power. But Cosgrove takes the braver path and shows the deep inadequacy of the modern secular religions that have replaced Christianity in the West. A religious life—after Nietzsche, Darwin, Einstein, genetics, quantum physics, the death of God—can be empty, but not as empty as a life lived in pursuit of money, celebrity, or World of Warcraft experience points.

Cosgrove's way of working is appropriately medieval too. What Manner of Person Art Thou? was lovingly animated by a single hand, over many years, just as medieval manuscripts were copied and illustrated, page by page, with great love. Cosgrove's imagery, too, draws heavily from medieval manuscripts, pictorial tapestries, and the woodcuts illustrating the earliest religious printed books.

Yes, Cosgrove is a heretic in a long tradition. At times one is reminded of the riddling, human-centered Christianity of Angelus Silesius (born Johann Scheffler in 1624) and his enigmatic epigrams: “GOD LIVETH NOT WITHOUT ME—I know God cannot live one instant without Me: If I should come to naught, needs must He cease to be.”

But, though Cosgrove is a heretic, her conclusion is one that would meet with the approval of Saul of Tarsus, who hunted and killed Christians before becoming Saint Paul. Like Paul, Elijah and Enoch find their view of the world in collision with others' view of the world. They solve the problem in a style that has become familiar: by chopping off the heads containing the alternative point of view. But finally from deep within their own bodies rises a yearning strong enough to smash the rigid shell of their own worldview, from the only direction in which it is vulnerable, the inside.

By smashing all these deluded realities, you could say that Erin Cosgrove is arguing for the idea that Parmenides came up with, five hundred years before Christ’s birth, and on which science is based: reality is not that which we experience.

But it is a strength of her surprisingly, pleasingly ambiguous work that you could also argue that she strips away the rigid, often intolerant shell of Christianity only in order to reveal its precious core. Its bleeding, sacred heart. She is agreeing with both Jesus and Krazy Kat—when science has stripped away everything, the one thing left that is powerful and true, that survives being explained in terms of chemistry, survives being understood in terms of genes, that can still overwhelm us, dissolve our brittle self, connect us to the universe . . . is love.

Notes

1. Quoted in Michael Ondaatje, The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2002), 308.

Julian Gough writes funny and increasingly indescribable novels. He was born in London, raised in Tipperary, educated in Galway, and lives in Berlin. His comic novel Jude: Level 1 was short-listed for the 2008 Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction. In April 2007 Gough won the BBC National Short Story Award, for “The Orphan and the Mob” (the prologue to Jude: Level 1). His previous novel, Juno & Juliet, was published in 2001.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay-Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley, the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund, and Fox Entertainment Group’s Arts Development Fee. Gallery brochures are underwritten in part by the Pasadena Art Alliance.