Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now

- – This is a past exhibition

Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now examines the woodcut in terms of its diverse forms and uses in the modern era. A thematic survey, it invites parallels between the medium in countries as diverse and geographically distant Mexico, France and Korea. Woodblock printing is, in fact, one of the most common artistic practices throughout the world. Although the motivations of each artist and the circumstances in which the woodcuts were made may differ greatly, the visual character of the gouge cuts is a defining thread among the selected works in this exhibition.

Curated by Allegra Pesenti, UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum.

Essay

By Allegra Pesenti

In its most basic form, the making of a woodcut requires just a block of wood, a cutting tool known as a gouge, some ink, and a sheet of paper. The birth of the woodcut can be traced back to the eighth century when Buddhist monks in Japan and China developed this basic printing practice to reproduce devotional texts.1 It did not establish itself in Europe until the beginning of the fifteenth century, reaching a technical and artistic apogee as a fine art medium in the hands of German master Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Although the medium evolved thereafter, especially with the introduction of color to the chiaroscuro woodcut, it fell out of favor towards the end of the Renaissance. While the woodcut continued to be a common source for the dissemination of biblical and folk scenes, intaglio printing techniques (such as etching and engraving) were considered to be more sophisticated means of aesthetic communication. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the woodcut served primarily to illustrate street banners and broadsides or as reproductions in popular journals and calendars. It was partly this popular aspect of woodcuts, together with their organic quality and an easy accessibility to the natural materials, which lured artists back to the technique towards the end of the nineteenth century. Paul Gauguin and his contemporaries in France rediscovered the pure, untainted character of the woodcut and set the stage for a host of artists who experimented with the medium thereafter. The woodcut’s archaic yet versatile qualities nourished its evolution throughout the twentieth century, and the technique continues to take new directions within the contemporary studio.

A MODERN MEDIUM

The works in this section trace the woodcut’s emergence as a modern medium, but a modern medium that retains a primal energy and ancient purity of form. Émile Bernard's Christ on the Cross (ca. 1890–91) is a daring print for its time. Few nineteenth-century artists had made woodcuts as independent works of art, and none had been quite so explicit in exposing the wood itself. A radical departure in the history of printmaking occurred when artists such as Bernard chose to favor the textures and imperfections of the plank itself and to incorporate them into their designs. The woodcut was no longer a poorer version of the engraving, nor did it aspire to look like one, but instead it became the vehicle for an entirely new and spontaneous graphic language. Paul Gauguin was a pivotal figure in this phase of aggressive innovation. An adventurous, irascible soul, Gauguin displayed a deep nonconformist attitude, eager curiosity, and yearning passion for the natural and the supernatural, all of which contributed to his momentous woodcut creations. Te Atua (1893–1894) is one of a series of prints the artist made in Paris after his return from Tahiti in 1893. It was intended for publication in Noa Noa (the Tahitian word for fragrance), a visual diary of his experiences on the island. The smoky, chiaroscuro effects in this early proof were achieved by variously inking and wiping the block. Working freely on the wood, Gauguin molded the desired tones that would best render the moody spirits and cavernous enclaves of the island.

The circulation of early-nineteenth-century Japanese woodcuts, with their juxtaposed colors and undefined perspectives, played an important role in the increased popularity of the woodcut in Paris from the 1880s. There was, furthermore, a communal effort among printmakers to increase public knowledge about the medium through the circulation of illustrated journals such as L'Estampe originale, which featured Bernard's Christ on the Cross, as well as some of the boldest cuts of the times by Félix Vallotton. Alfred Jarry—perhaps best known as an avant-garde playwright—was himself a woodcut artist and a promoter of the medium in L'Ymagier, the short-lived journal he co-founded with Rémy de Gourmont, which focused on popular and devotional images. Of note in the context of this exhibition is L'Ymagier's publication of woodcuts made around 1870 in Calcutta.2 Rare examples of these Indian works, which range from scenes from the life of Krishna to secular portraits, are displayed in this section. Their spontaneous style, swift delineations of form, and raw, straightforward imagery predict the work of Henri Matisse and his contemporaries in France. Whether produced for the fine art collector or a visitor to an Asian shrine, the woodcuts of this period share a vigorous common vocabulary.

The independent nature of the woodcut was a key factor during the modern period. Woodcuts can be achieved without a press, the use of acid, or the participation of a professional printmaker. The Norwegian artist Edvard Munch experimented freely with blocks, extending the creative possibilities of the medium. He explored multiple possibilities in each composition so that the woodcuts, such as the rare impression of Towards the Forest (1915), are in fact unique works. The woodcut is also the most sculptural form of printmaking, as witnessed in the modeled and tactile block for Matisse’s Nude Seated in Profile on a Chaise Longue, The Large Woodcut (1906), allegedly cut by the artist's wife.

The gouge line becomes increasingly raw and unedited from the outset of the twentieth century. Emil Nolde's deeply evocative portraits, for example, emerge out of darkness, with just a few splintered strikes of the block. The German Expressionists were directly inspired by sculptural artifacts and ethnic carvings for their own spontaneous cuts. Paradoxically, the woodcut’s association with an earlier, more spiritual, and less materialistic age appealed to artists who wished to transcend historical and cultural barriers and create new waves of modernism. Wassily Kandinsky's seminal book Klänge (Sounds, 1913) traces a stylistic voyage in woodcut form, from folkloristic figurative compositions to pure abstraction. Woodcut was also the chosen practice of Czech artist Joseph Váchal, whose witty yet demonic scenes seem to belong both in the Dark Ages and be ahead of their own time. Váchal is little known, but his Seven Deadly Sins (1912) conveys his powerfully original mind and inspired use of the gouge.

IMAGES IN THE GRAIN

Traditionally, to create woodcuts artists carve the side grain, the more malleable plank side of the wood, rather than the harder end grain. For many artists, the textured, organic quality of the wood itself and the natural forms of its grain are the principal appeal of the woodcut practice. While the grain had been incorporated in compositions by Japanese printmakers and by Gauguin and Bernard in the 1890s, the curves and uneven patterns of the wood first come to the forefront of the image in the work of Edvard Munch. In The Kiss (1897–1902), the subject is intimately bound to the medium. The embracing couple is formed out of a single block, painted black, and attached to the rest of the block like a piece in a jigsaw puzzle. The figures blend into the background of pure “plank,” with its prominent vertical lines that pour down the composition like a sudden autumnal shower, yet the lovers remain distinct from their environment and silently oblivious. The character of the wood, which Munch may have soaked to raise the grain, conveys the mood of sensual melancholia and isolation.

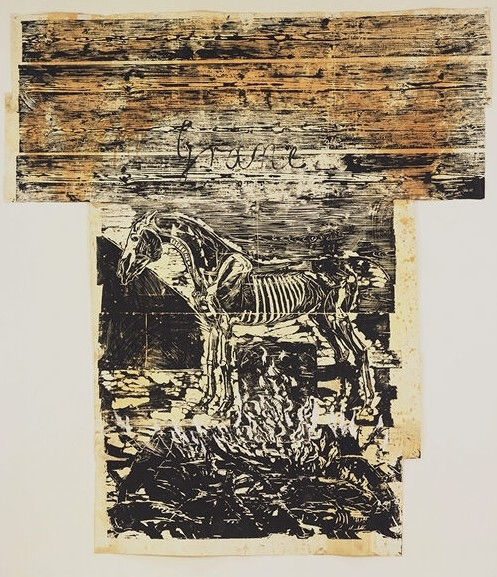

The tradition of woodcut is particularly strong in Germany, where artists investigated new angles on the technique throughout the twentieth century and continue to do so today. In Woman's Profile (1917) by Emil Nolde, the haunting portrait is interlaced with the vertical grain of the wood. Joseph Beuys worked on a series of five woodcuts beginning in 1948; they are cut on coarse, cracked planks that he may well have rescued from a discarded batch of floorboards. In Beuys's Hind, a graphic, prehistoric-looking motif of a female deer is tenuously incised along the grain. To create his monumental work Grane (1980–93), Anselm Kiefer printed large planks of wood that dramatically reveal all their rawness and roughness. The title refers to a mythical horse in Richard Wagner's operatic drama Der Ring des Nibelungen—in an act of passion, the heroine Brunhilde rides Grane into the burning pyre where her beloved Siegfried lies dead. In Kiefer's work, the horse stands alone amid the fading flames. The artist's physical engagement is felt here, both in terms of the grand scale of the work and the sweeping cuts: the medium is integral to the subject.

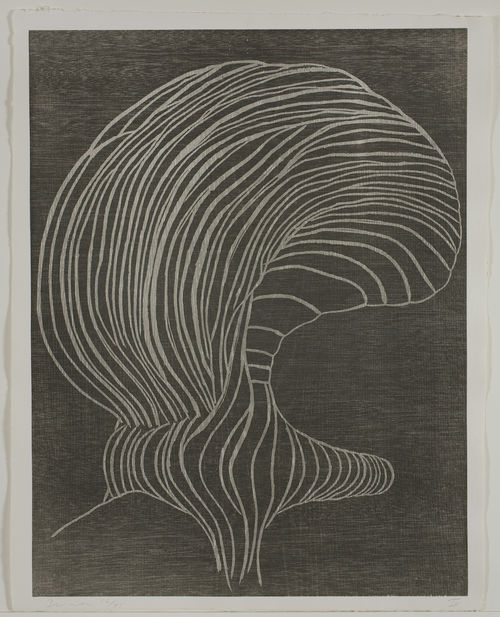

Artists continue to experiment with the natural forms of the wood, play with them, and use them to their full effect as an essential aspect of the artwork rather than as the mere medium through which it is realized. American artist Terry Winters pushes the boundary between figurative and abstract imagery in his series Furrows (1989), where the grain is very subtly revealed within a pattern of loose, undulating grooves; here, the pure forms of the wood are alluded to within an imaginary floating world of medusa or marine-looking forms.

THE VOICE OF THE ACTIVIST

Works on paper often reveal with particular intimacy the touch of the maker's hand. Frequently associated with the private world of artists, they seem to allow a glance at the creator's thoughts, much like reading a diary. While woodcuts are certainly used for these more intimate expressions, the medium has also been a powerful vehicle for public expression. The gouge line can be loud and evocative and is associated with a strong tradition of social and political activism. Created with accessible and low-cost materials, woodcuts offer the artist in most parts of the world the freedom to work independently. The examples gathered here, whether from Mexico, Germany, Korea, or elsewhere, all carry the weight of the artist’s hand and mind, and in them we encounter a new monumentality in size and message. However diverse in origin and motivation, the works gathered in this room confront the realities of history while highlighting the malleable possibilities of the woodcut.

The largest work on display is The Pseudo-Republic and the Revolution by Carmelo González Iglesias, a visual outcry depicting the Cuban Revolution and a tour-de-force of loaded imagery and technical bravado. It was finished in Havana in 1960, a year after the dramatic overthrow of General Fulgencio Batista's government, which was led primarily by Fidel Castro and rebel troops. González had planned to compose the print out of two blocks, but in a letter describing the work he admits that since political events were unfolding by the day, he kept adding to the composition until it reached the width of seven blocks!3 He advises reading the work from right to left, “the same route as the history of Cuba.” The artist’s vocabulary is rich with symbolic associations. At center, three superimposed hands refer to the stages of protest: an open hand indicates initial resistance to the government; a tight fist symbolizes wrath; and finally, we see the fist that is compelled to clutch a weapon. Similar emblematic imagery appears in the work of González's pupil, Luis Peñalver Collazo, who simulates the conflict between Latin America and imperialism with two broad, shady figures in battle (1960). Although conceived to serve as street banners, these examples of mural-like prints were given to an American scholar by Ernesto “Che” Guevara himself.4

The Cuban woodcuts are related to a tradition of activist printmaking initiated in Mexico in the 1930s. The heritage of Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada's late-nineteenth-century broadside illustrations, especially his satirical scenes populated by calaveras (skeletons), can be seen in the public art that continued to flourish in Mexico thereafter. Woodcut was the only technique available to David Alfaro Siqueiros during his 1930 imprisonment for communist activities. Using scraps of salvaged wood, he conceived a series of small scenes with abstract form but intense symbolic meaning. Woodcuts and linoleum cuts were central to the practice of the Mexican graphics collective El Taller de Gráfica Popular (Workshop for Popular Graphic Art), known as the TGP. The experimental workshop lured artists from abroad, including African American printmaker Elizabeth Catlett, whose portrait of a female sharecropper of 1952 is a vivid commentary on the status of women and the underprivileged classes. The gouge proved an effective tool for the TGP’s blunt imagery, and the print medium served their objective to project sharp, straightforward messages to a wide audience. The activist woodcut tradition lives on today, notably in the ambitious works of Artemio Rodriguez, an artist who shares his time between Tacámbaro, Michoacán, and Los Angeles. These politically charged prints are similar in scope, aspiration, and visual power to the great murals of Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco.

A parallel tradition of socially conscious woodcuts exists in Germany, ranging from the coarsely cut manifestos of the German Expressionists to the contemporary portrait cycle The Ring (2000) by Thomas Kilpper. In Georg Baselitz's The Eagle (1981), the iconic emblem of the German Federal Republic is depicted head down; its scratchy white outlines offer a striking, deliberate contrast to the stark black background. In Germany, as in other countries, the woodcut medium has lent itself to heroic portrayals of figures from the fringes of society. Here, Christian Rohlfs's The Prisoner (1918) shares the same critical intent as Scottish-born Peter Howson's depiction of a brooding homeless man in The Heroic Dosser (1987).

The activist woodcut is not always destined for wide distribution, nor does it need to be visually boisterous. For example, a silent but powerful image is proposed by Zarina Hashmi in Dividing Line (2001): the line that creeps down the cream-colored sheet represents the border between India and Pakistan and the partition of Hindus and Muslims. Zarina's reversal of the typical white on black technique—an effect achieved by carving out the background rather than the line itself—endows the image with an ethereal lightness.

SACRED CUTS AND DEVOTIONAL IMAGERY

The woodcut has been a preferred medium for devotional purposes in many different historical periods, from the earliest datable examples of Asian sacred texts around 770 AD to the present day.5 Whether personal interpretations of religious themes or images made for devotional use, all of the works on view seek to engage the viewer's senses and inspire a state of contemplation.

Some of the most visually and spiritually engaging works belong to the long-standing school of woodblock printing associated with Buddhist monasteries in the Himalayan regions of Tibet and Nepal. The religious institutions themselves have largely been responsible for the production and distribution of sacred images, and some still maintain large archives of blocks. Here, there is no notion of “traditional” or “modern,” and the incentive is not necessarily to renew iconography and artistic forms but rather to maintain the survival of texts, emblems, and divinities that have been part of the culture's ceremonial history for centuries. When a block shows deterioration, its design is transferred to a new one, and thus the image is preserved in perpetuity, as is the craftsmanship involved in carving the block. It is a process done entirely by hand: prints are usually made without the use of a press; the ink is prepared from soot, burnt rice, or barley grains; and the Nepalese paper is made from local tree bark. Often the image itself is not seen by anyone except the lama at the time of consecration, after which the sheet is folded and bound into an amulet. Some are printed on cloth and used as prayer flags, while others may be rolled up and eaten as medicine. Those that have survived intact, such as the ones on view here, were conceived for display either within the monastic setting, on altars, or for domestic use (pasted in specific places on the walls of the layman’s home). All claim auspicious powers and belong to a complex matrix of religious beliefs.6 Even displayed here, removed from their original contexts, their bold and vibrant symbolism captivates the onlooker.

The fervent devotion towards the goddess Kali in Bengal, India, and the popularity of a temple dedicated to her in Calcutta inspired Kalighat pats, a type of devotional painting on paper. The peculiar, spontaneous style of these works differs greatly from the detailed, miniaturist tendencies usually associated with Indian art on paper. Throughout the nineteenth century, these Kalighat paintings were sold to the crowds of pilgrims who visited the temple, and so they had to be produced rapidly and in large quantities. Images range from scenes connected to Hindu mythology to depictions of social customs and contemporary society. After about 1860, the liberated style and colorful palette of these works were adopted by printmakers from Battala, an area in old Calcutta that still today is the center of printing and publishing. The craftsmen there embraced the woodcutting technique, imported by the British, and made it their own. These artists, driven in part by competitive price pressures imposed by the thriving market around the Kalighat temple and local fairs, created an array of dynamic, visually enticing scenes to sell to tourists. Once printed, the images were often liberally touched up with dabs of red, yellow, or green watercolor. The Holy Child of Aracoeli (ca. 1880), on view here, is an exceptional rendition of a miracle-performing wooden sculpture in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli in Rome. The image reflects the presence of European Christian missionaries in Calcutta at the time. Due to the climatic conditions in India and to the cheap paper these works were printed on—it is the same type used for kites—only about 100 are known to survive today. The examples on view are exhibited for the first time in this country, and all belong to a rare group bequeathed by British collectors to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In style and content, these quickly produced souvenirs are no less daringly innovative than the German Expressionist prints by Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff displayed nearby.

The tradition of using woodcuts for religious imagery evolved in different ways throughout the twentieth century, and it continues to provide a point of departure for artists today. Drawing on a tradition of printed prayer books and literary texts that stretches back over centuries, Korean artist Shin Young-ok has woven streams of paper cut from a woodblock-printed book into five separate three-dimensional scrolls in The Ways of Wisdom (2000). Her reinterpretation of the woodcut medium and the historical inspirations behind it encapsulate the core motivations of the artists in this exhibition. Although rooted in the distant past, the woodcut form has evolved over the centuries while still retaining the essence and energy of the gouge.

Notes

1. See Sören Edgren in Cynthia Burlingham and Bruce Witeman, eds., The World from Here: Treasures of the Great Libraries of Los Angeles (Los Angeles: UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum, 2001), cat. 43, pp. 107-09.

2. Eric Forbes Robertson, "Les Dieux: Huit bois Indiens taillée à Calcutta," in L'Ymagier (January 1895), pp. 79-93.

3. Letter from Carmelo González Iglesias to Gordon L. Fuglie, former curator at the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, dated October 1, 1984. The final dimensions are 51 7/8 by 169 inches.

4. See Lynn Anderson and Gordon L. Fuglie, Three Murals from Revolutionary Cuba, 1960 (brochure for an exhibition at the Wight Art Gallery, UCLA, 1985).

5. See note 1.

6. For further reading on Himalayan prints, see Nik Douglas, Tibetan Tantric Charms and Amulets: 230 Examples Reproduced from Original Woodblocks (New York: Dover, 1978); and Katherine A. Paul, “Words on the Wind: A Study of Himalayan Prayer Flags” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2003).

Gouge: The Modern Woodcut 1870 to Now is made possible by a major gift from Susan Steinhauser and Daniel Greenberg, Ruth Greenberg and the Greenberg Foundation.

The exhibition is also generously supported by Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Barbara Timmer and Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer.

Additional funding is provided by Anawalt Lumber Co., The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, Astrid and Howard Preston, the International Fine Print Dealers Association, Bobbie and Robert Greenfield, and Patricia and Richard Waldron.