...And Then Again: Printed Series, 1500-2007

- – This is a past exhibition

This exhibition examines the development of serial imagery in prints, from the early European Renaissance to the present day. Drawn primarily from the extensive collection of works on paper in the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, the exhibition is one in an ongoing series of exhibitions focusing on the Hammer’s permanent collections.

First inspired by the printed book in the late fifteenth century, early printed series frequently depicted narrative subjects drawn from literary sources. Biblical themes or mythological subjects were portrayed by a wide range of Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer and the German “Little Masters.” Traditional subjects such as the Times of Day, Twelve Months, and Four Seasons offered an ideal pretext for the representation of landscape by Dutch artists of the seventeenth-century. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries witnessed the development of the improvisational capriccio and artists such as Jacques Callot, Francisco Goya, and Giovanni Battista Piranesi invented variations on fantastic and dramatic themes in printed series. These themes of time, landscape, narrative, and capriccio are also explored in contemporary printed series by artists such as Christiane Baumgartner, Chris Burden, Mona Hatoum, and Chris Ofili.

The variety of ways in which artist have explored the serial image reminds us of the rich dialogue that can take place across centuries and cultures and of the enduring importance of the series in visual arts.

Organized by Cynthia Burlingham, director of the Grunwald Center and deputy director of collections at the Hammer Museum.

Essay

By Cindy Burlingham

Throughout the history of art the series format has offered seemingly endless possibilities for artistic representation and variation. This is particularly true of the art of the early European Renaissance, when a diverse selection of narrative, allegorical, and formal serial subjects appeared in various forms, from paintings to playing cards. The serial format proved particularly appropriate for the increasingly widespread artistic practice of relief and intaglio printmaking, which allowed for the representation of a wide range of subjects with multiple images in relatively small, portable, and easily expandable form. Among the most familiar themes were the Twelve Months, Four Seasons, and Times of Day, subjects that not only suggested the passage of time but also functioned as allegories of the course of human life. Suites of saints, virtues, vices, the signs of the zodiac and the seven liberal arts were also common, as were narrative series that recounted stories from the Bible and other religious and mythological subjects such as the Labors of Hercules, the Flight into Egypt, the Passion of Christ, and the Life of the Virgin.

Although the printed series first developed as part of the printed book, their paths diverged toward the end of the fifteenth century as images assumed a primary role, leading to the realization of the independent printed series. The most significant early example of this development was Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse, the first book to be both illustrated and published by a major artist. Though published in book form, the sixteen full-page woodcuts dominate rather than follow the accompanying text. Dürer produced additional series of woodcuts and engravings, with and without text, of such popular religious subjects as the Life of the Virgin and the Passion of Christ. His small engraved Passion was particularly influential for the sixteenthcentury artists Hans Sebald Beham, George Pencz, and other so-called German Little Masters, who created numerous series comprising small, meticulously engraved scenes of biblical and mythological stories.

In the seventeenth century landscape became an increasingly popular subject, particularly in the Netherlands, where printed series incorporated realistic and identifiable depictions of the local countryside. Traditional subjects such as the Times of Day, Twelve Months, and Four Seasons offered an ideal pretext for the depiction of landscape. Jan van de Velde’s abundant prints of these subjects were innovative in their depictions of the Dutch landscape and their use of atmospheric and naturalistic details. Other artists went even further toward the development of landscape as subject, producing printed series with multiple individual views of the local countryside, in effect documenting the experience of a peaceful stroll in the country.

Jacques Callot’s oeuvre of more than fourteen hundred prints includes numerous series, testifying to the varied and innovative approaches to the format developed in the seventeenth century. His influential and harrowing Large Miseries of War of 1633 chronicles the relentless warfare of mercenary armies in the Duchy of Lorraine. Callot also etched a number of series depicting single figures, such as the Capricci di varie figure and the Varie figure gobbi which demonstrate the casual calligraphic quality of the etching medium. These variations on a theme, or capriccios, demonstrate the artist’s imagination and talent for improvisation and invention.

The capriccio featured prominently in printed series produced in the eighteenth century. Giovanni Battista Piranesi specialized in architectural fantasies, and among his most mysterious and haunting works are the Carceri (Prisons)—large, dramatic, and densely worked etchings of imaginary prisons. Francisco de Goya’s first major printed series, the Caprichos of 1798–99, and his second, the Disasters of War, used the improvisational capriccio to explore even more disconcerting topics. Because of its controversial subject matter the Disasters was not published until 1863, thirty-five years after the artist’s death. Its eighty prints depict the Spanish resistance to Napoléon’s invasion from 1808 to 1814, famine in Madrid in 1811–12, and images that allude to the repressive government of King Ferdinand VII. Like Callot’s Miseries, Goya’s Disasters does not generally reference specific sites or persons. But in contrast to Callot’s small, distanced views populated by numerous tiny figures, Goya focuses on dramatic moments and individuals that symbolize the essence of these hostile episodes.

Throughout the nineteenth century depictions of landscape, both real and imaginary, remained a focus of the printed series. John Martin’s mezzotint series of 1824–27 illustrates the complex narrative of John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost with sublime imaginary landscapes. Hiroshige’s Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Road of 1832–33 is part of a larger tradition of topographic landscapes intended for travelers in both Japan and Europe. In their topographic specificity and extensive number, the prints re-create a long journey, conveying a sense of the passing of time. The series was so popular that it was published in at least ten different versions.

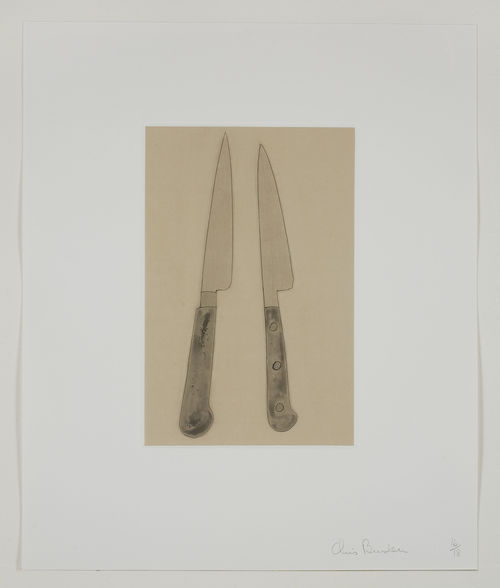

The printed series remains an appealing format for contemporary artists, providing a platform for investigation of themes of narrative, sequence, interaction, and variation. Chris Burden’s 2006 Coyote Stories details the artist’s encounters with coyotes at his canyon home and studio through images and a narrative diary. Mona Hatoum’s 2004 portfolio, hair there and everywhere, with its varied compositions made from the artist’s own hair and printed in soft-ground etching, also could be considered a capriccio. Chris Ofili depicts the same moment from different points of view in his Agony in the Garden of 2007. Richard Tuttle’s 1998 Mandevilla series features what the artist describes as a “call and response” interaction among the prints. Christiane Baumgartner’s woodcuts are based on video stills, with images transferred from a high-tech medium to a traditional one. In her 2007 series Deutscher Wald, a disheartening view of the passage of time is implied by the disintegration of images of trees, printed in red. The variety of ways in which these artists have explored the serial image reminds us of the rich dialogue that can take place across centuries and cultures and of the enduring importance of the series in the visual arts.

Cynthia Burlingham is director of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA, and deputy director of collections at the Hammer Museum.