Hammer Projects: Walead Beshty

- – This is a past exhibition

In 2001, Walead Beshty happened upon a short article in a German newspaper about the Iraqi diplomatic mission located in former East Berlin. Due to shifting political regimes, it is now a space occupied by countries whose sovereignty is either defunct or in question. Abandoned for over ten years, this embassy turned squatter's haven now offers only glimpses of its past life of ambassadors and dignitaries. Beshty traveled to the mission repeatedly, collecting photographs, speaking to former Iraqi officials, and even taking up residence for a short period.

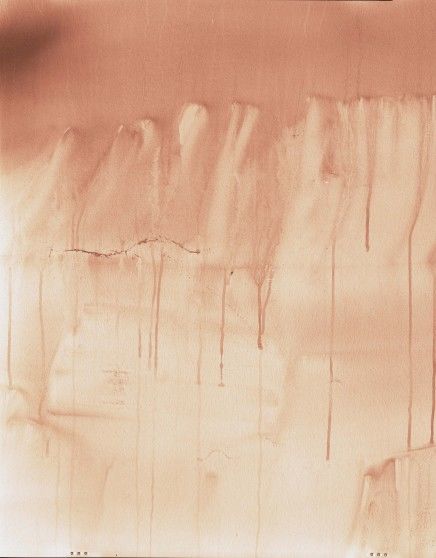

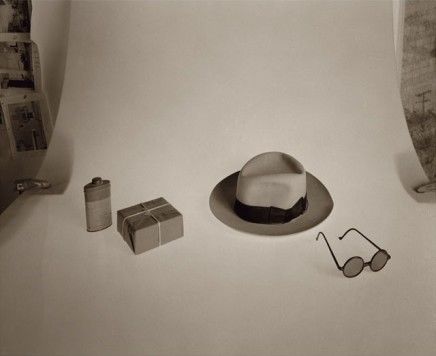

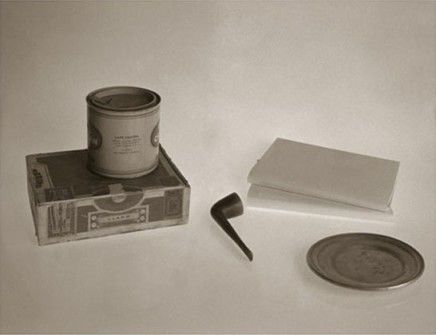

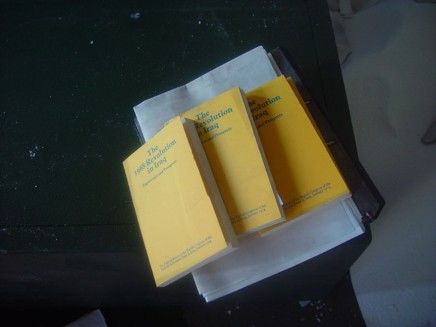

Beshty's installation acts as a portal to the mission and includes a brutalized bag of embassy ephemera that bears the marks of an inspection by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security; waiting room furniture; reading material; and a telephone line that connects museum visitors to a phone at the mission in Berlin. The image of the mission's facade is a composite of two photographs, one spanning the transition from night into day, the other from day into night; other photographs record the impressions of books left after a recent fire. The larger works document the scars on Beshty's camera film left by airport x-ray machines and security checkpoints in its movement across international borders. Their vaporous discolorations add an unexpected beauty to the office debris.

Beshty's work explores not only the history of photography, but also the way in which photography shapes our understanding of history. He makes this enduring relationship visible by bringing together images of ambiguous places, altering them, and exhibiting them as documentation. Beshty invites the viewer into a surrogate of a place that, though real, by legal definition does not exist. This tenuous link between what is authentic and what is reproduced parallels the medium of photography itself, which captures moments in time that our eyes are trained to believe truly occurred. Beshty's work offers us a chance to experience the sense of uncertainty that this place engenders, lying unsteadily on a line between past and present, fact and fiction, day and night.

Biography

Walead Beshty was born in London in 1976 and currently lives in Los Angeles. He received his MFA in 2002 from the Yale University School of Art and his BA from Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, in 1999. He is on the faculty of the Department of Art at CalArts, Valencia, and has served as a visiting lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles and Irvine. Beshty has had solo exhibitions at P.S. 1/MoMA Contemporary Art Center and Wallspace in New York and at China Art Objects Galleries in Los Angeles. His work was also included in group exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; the Whitney Museum of American Art and White Columns in New York; and the DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, Massachusetts. In October, the artist will participate in the 2006 California Biennial at the Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach. Reviews and articles on Beshty's work have appeared in Artforum, Frieze, and The New Yorker.

Essay

The following are excerpts from a conversation between Walead Beshty and Aimee Chang about Beshty's Hammer Project based on the abandoned Iraqi diplomatic mission in Berlin.

Walead Beshty: In 2001 a friend showed me a short blurb in the newspaper about a fire in the abandoned Iraqi diplomatic mission to East Germany (GDR). It was right around the time when the U.S. was going into Afghanistan and the current war with Iraq was about to happen. The newspaper article indicated that it had been abandoned but that it was still filled with debris, which squatters had used to start a fire that had gotten out of control. I started to research it and ended up visiting the site soon after, finding out that it had been abandoned sometime between the Berlin Wall coming down and the first gulf war. The site itself was given by the GDR to Iraq in perpetuity, which was unusual, so even after reunification it continued to be Iraqi soil. It is something of a snapshot of the end of the cold war; it seems that everything had been left behind in a hurry. It made me think of the stories about the abandoned colony at Roanoke. I returned several times and produced a preliminary work about the site with Eric Schwab, which we published in 2003.

The diplomatic mission initially interested me because of its state of perpetual ruin. It is unique as a ruin in that it isn't simply neglected, but is marooned by international law. German teens looking to drink beer and hang out can sneak in, but no agent of the state can legally set foot on the grounds because of laws protecting national sovereignty, even though the GDR and the Republic of Iraq no longer exist. From a legal standpoint it is invisible, and one can become invisible by entering it. While the mission sits next to virtually identical buildings, connected to them by proximity, it is actually completely detached, a part of another country, a nonexistent one. You can hop a fence and enter international limbo, a sovereignty-free zone . . . entering it is a kind of time travel. The idea for the Hammer exhibition is a kind of cold war waiting room; it seems we are left with large fragments of cold war mentality. Language about evil empires still exists, though such phrases seem strangely anachronistic, like the Iraqi diplomatic mission itself. I want to extend the odd stasis of the mission, its place between moments and meanings. That indeterminacy is why the Lobby Gallery is so attractive to me; as a space it is between inside and outside, a middle ground.

Aimee Chang: There is this idea of photography inciting reverie or embodying a sense of nostalgia. What's interesting to me about these photographs is that, rather than being about a time or person from the past, they are of a place that has passed away politically, but not actually, and I think that what replaces that nostalgia is a political examination.

WB: One would think that relics of past ideologies could have the potential to pose questions regarding the stability of our current beliefs, yet we've found a way to excuse this, to use them to support our current ideas, by turning them into monuments, memorials, or “sites,” to infuse them with nostalgia, to make them “pictures.” This process avoids ambiguity by naming it, and photography is another form of naming. There is very little that one could claim as auratic about the mission itself; it is completely banal, bureaucratic. Photography is similarly bureaucratic in its depiction, banal even, but it's a tool that has an oddly effective hold on our imaginations. It is easy to look at much photography with poetic longing; its seduction is like the seduction that ruins have. But the choices that govern the form of pictures have historical implications; they often preserve and destroy in the same gesture. The U.S. geological surveys are just one of many such instances: on the one hand, they preserve the image of an unspoiled American West, yet, on the other hand, they are deeply implicated in the course of events that radically changed it. The same is true of the heliographic mission in France. In the act of viewing them now, we project an anterior historical fantasy after the fact. Monuments also operate like this. But if we look at their history, we see that image and place are inextricably linked, conflated even. To me, that connection, that impact, is most compelling. In the case of the Iraqi mission, the question became: “What aesthetic model or program really is at stake here? How can photographs be used in a way that is not purely monumental?” Thinking about these issues in relation to aesthetics became a really tricky thing to sort out. I wanted to avoid short-circuiting those conditions into a simple image or into something that glossed over the contradictions at play; a similar set of contradictions exist in many places. I did not want to participate in the production of iconic images of destruction; there are too many already. The mission is too banal for its destruction or decay to be heroic, and that interested me.

AC: What is interesting to me is the project;s assertion of presence. It's an assertion of a presence that is absent. I think this is evident in some of your other work too, like your documentation of the foundation of Albert Speer's unbuilt triumphal arch for the Third Reich or the failed housing projects in Excursionist Views. They are about these things that have no space within the historical narrative but that actually still exist in a very material format.

WB: That's why I think I'm drawn to relics, to things that seem to have lost their place. . . . The cultural associations in a lot of the material I work with are established, but within them there are messy parts that don't fit. With Speer's triumphal arch, the obvious questions are confounding: “Why is that foundation still sitting there? What does it mean that it's still around?” It hasn't been compartmentalized or defined yet; no one knows what to do with this blank concrete column: it's not grand enough to be a monument, and it's not marginal enough to just demolish. So it just sits there unaccounted for. Berlin is one city that is constantly negotiating with these questions, questions of aesthetics, history, trauma, and memory. With the mission there's still a possibility to think through what's at stake, what such relics might mean. It can't be excused with narratives about the war or the triumph of the West over communism; it resists these stories. It is extremely difficult to situate it within the dominant logic that it's supposedly a part of. It doesn't lend itself to a claim for the war with Iraq or one against it; you can't instrumentalize it in this way. Likewise, neither an act of preservation or collective acknowledgment nor its destruction really resolves its contradictions. Even the question of what history it truly belongs to is contested. While it is physically discrete, it is geopolitically expansive, extending to places thousands of miles away. It affirms the presence of possibilities between absolute choices; there are no idealized responses available. It serves as a reminder that there are real situations that don't fit into this either/or dichotomy or into overarching structures of belief. The hope is to try to work in these contradictions because they offer a way out of this fiction that the only options are true belief and total cynicism.

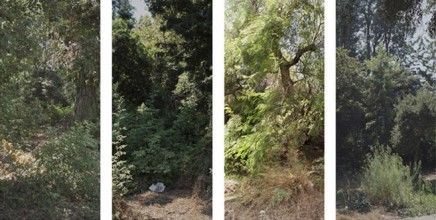

Such indeterminate sites interest me, which is why I was drawn to the architecturally experimental but socially failed housing projects in the Excursionist Views, or to the highway medians in the Island Flora series, or to the Dead Malls I photographed. All were in some form utopian, beautiful . . . equally bleak and yet hopeful in their own ways. I believe that in these indeterminate, temporary, disposable, marginal spaces, some sort of reimagination can occur. The issue is not to “document” them, to use photographs to simulate a faux transparency, but to expand the indeterminacy to the act of viewing. Most of the spaces we operate in are marginal or indeterminate in this way; these extreme examples help me understand the conflicted identity of the spaces we tacitly agree are concrete and stable. Pictures make things appear stable; one way to get at this issue is to make photographs that attempt to deal with their own instability, not just to claim them as fiction or fact, but to see their meaning in the fantasies they engender, to accept this without sleepwalking through it.

Aimee Chang is Exhibition Coordinator and Assistant Curator at the Hammer Museum.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Fox Entertainment Group's Arts Development Fee, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.

Support for this Project was also provided by ART2102, Los Angeles.