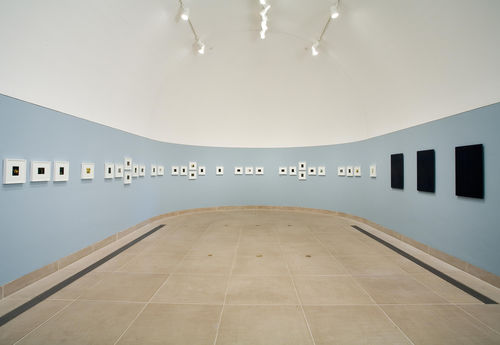

Hammer Projects: Miranda Lichtenstein

- – This is a past exhibition

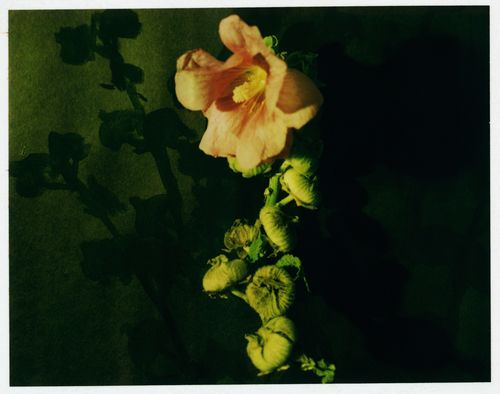

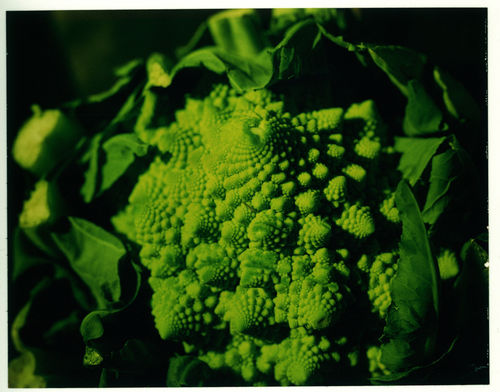

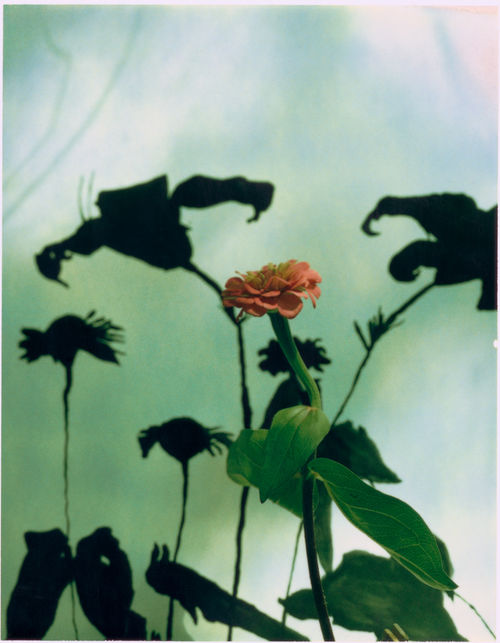

Miranda Lichtenstein's Polaroid photographs capture moments of transient, dark beauty. Taking her cues from early plant photography, the gardens of Giverny, and 18th-century paintings by Chardin, she bathes the living matter in a wash of artificial golden light. Making use of the most traditional elements of the still life-flowers, plants, fruits, and vegetables-she imbues them with a disquieting quality. This is produced, in part, by the painted backdrops in front of which she places her subjects. Shadowy, slightly misaligned, these backgrounds subtly destabilize the relatively traditional still-life format.

Biography

Miranda Lichtenstein was born in 1969 in New York, where she currently lives. She completed her undergraduate studies at Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, New York, in 1990 and received her MFA in 1993 from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia. She has had recent solo exhibitions at Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York; Gallery Min Min, Tokyo; and Mary Goldman Gallery, Los Angeles. In 2001, Lichtenstein’s Polaroid photographs were the focus of an exhibition at the Whitney Museum at Phillip Morris, New York. Her work has also been included in group exhibitions at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco; the Renaissance Society, University of Chicago; and the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. Reviews of her work have appeared in numerous publications, including Artforum, Art in America, and The New Yorker.

Essay

By Malik Gaines

Through her evolving practice, Miranda Lichtenstein has consistently found ways to mystify the certainties of photography by aligning them with more ambiguous painting traditions. The artist is a photographer first and a conceptual one at that: she moves ideas through her modern medium with its chemical processes and verisimilitudes, managing its materials like practical instruments of science. But still, Lichtenstein’s romantic sensibility alters the nature of the camera’s authority over the real by turning its lens toward the imagination. Just as her early series Lovers Lane (2000) treated wild, isolated environments with the eerie dramatics of the nineteenth-century sublime, so does her latest project blend typological photography with European painting movements contemporaneous with the camera’s invention, employing both the heavy presences of eighteenth-century still lifes and the squinty-eyed mistiness of French impressionism.

Although Lichtenstein avoids corny anachronism with a synthesis of content and form that’s distinctly contemporary, her projects have the power to evoke an olden-days moment when photographs and paintings began to emphasize their distinctions. Rather than posing this schism as a crisis of seeing or some other emergency of today’s subjectivity, she allows the borders to slowly bleed, letting a little magic seep into what’s real, and vice versa.

Lichtenstein’s new series of Polaroids reminds us that beauty and understanding can indeed coexist and, in fact, often produce each other. In her work—as in the early photographic experiments of William Henry Fox Talbot, who thought that capturing a landscape’s imprint on paper would be a charming alternative to sketching it; or in Eadweard Muybridge’s famous animal locomotion photos, which unraveled age-old mysteries of life’s form; or even in the elegantly specific illustrations of John James Audubon, which captured particulars of native species in intricate detail—the replication of nature, and the desire to do so, is not simply a tool to further humankind’s progress or to achieve artistic realism, but is a thing of transcendence. Take, for instance, Lichtenstein’s Untitled #8 (flower) (2005). A single pink flower atop a bent green stalk, an ordinary sort of thing, stands before a shadowy backdrop of flowers past and future. In itself, this little being epitomizes the futility and grace of life, the dendritic patterns of its leaves representing all of us and, captured here in a glint of light, keeping forever safe the delicate thing’s impermanence. Behind the flower, black figures loom against watery greens and blues, a backdrop that resembles a pond reflecting the evening sky. The dark silhouettes suggest infinite flowerness. Their distinctions are an obvious product of Darwinian speciation, and yet the looming quality they share conveys something otherworldly. Between the unimposing pink blossom that one might have picked up on the side of the road and the more universal gestures of flowers behind it is a space where the flower and the idea of the flower merge. Here is where knowledge and imagination grow into each other in an indistinguishable thicket and the viewer, experienced as she is in separating fact from fiction, is encouraged to let such differences drift away into a dusky mist.

In the terms of today’s photography, this loss of objectivity could be described as a failure. Works that visualize concrete typologies, such as the industrial photography of German conceptualist photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, have influenced Lichtenstein’s sense of what the medium is for and prevail in the discourse that surrounds photography as art. But Lichtenstein has consistently turned this documentary instinct toward systems that don’t work as they are meant to, especially systems that fail at taming nature. The artist uses a camera as one might use paint and canvas: as a tool for re-creating something real through the prism of one’s flawed senses, executed with subjective technique. In painting, this has been done with the understanding that the representation will never be real, despite helpful interpretive tricks like the camera obscura, a tool painters have used since the Renaissance to flatten what they saw into two dimensions. This artifice of painting is in opposition to the “genius” of photography, as Roland Barthes put it, which is presumed to have always really captured a little of what it displays. For this series, Lichtenstein has again brought photography to painting’s edge, specifically conflating ideas that emerge from her own art historical interests, including the turn-of-the-century botanical photographs of Karl Blossfeldt and the eighteenth-century still-life paintings of French artist Jean-Siméon Chardin.

Although these photographs suggest a critical consciousness of the histories they employ, the primary source for this work, as with many of the photographer’s series, was a particular, vivid experience. While an artist-in-residence at Giverny, the site of Monet’s historic gardens, which are still carefully manicured to create the lovely flow of gentle disarray, Lichtenstein spied a toolshed in which the outlines of various garden implements were painted on the wall, indicating an organizational master plan. But the tools themselves were in all the wrong places. This displaced typology can be seen in the drawings Lichtenstein made to place behind her photographic subjects. The various fruits and flowers she documents don’t quite match up with their backdrops, and the artist’s hand is evident in creating this arrangement. Further heightening this expressive mark making is the fact that these are Polaroid images, photographs that possess the direct imprint of the light that created them. Process is a key element in this work, but not process for its own sake. Like those of science and poetry, this process is important because of its results. While each of these images proves only itself, the entire project shows that Lichtenstein is an artist who can skillfully manage history and presence, criticality and gesture, and above all, the slightly sinister beauty of a natural world in which we and the flowers are real, living participants.

Malik Gaines is a writer and performer based in Los Angeles.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Fox Entertainment Group's Arts Development Fee, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.