Hammer Projects: Brenna Youngblood

- – This is a past exhibition

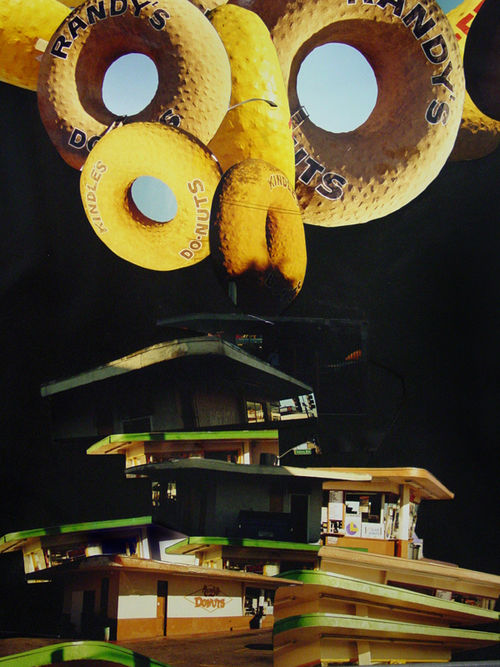

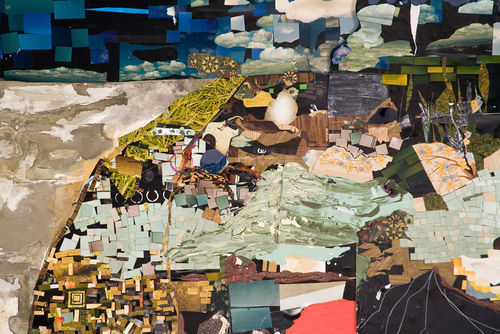

Brenna Youngblood's photographic collages are drawn from her everyday life, broken apart and re-assembled. Figures, architecture, and decorative backdrops are fragmented, multiplied and layered to form dynamic, chaotic rhythms. Youngblood uses her own archive of photographic images and details, from which she pieces together mosaic-like versions of her environment and community. Police cars, storefronts, and people in the artist's life intertwine, conjuring up personal, social, and cultural situations that are sometimes sinister, sometimes humorous.

Biography

Brenna Youngblood was born in 1979 in Riverside, California, and currently lives in Los Angeles. She received her BFA in 2002 from California State University, Long Beach, and will receive her MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, in 2006. She participated in group exhibitions at Hayworth Gallery and Compact/Space in Los Angeles in 2004. Her photographic collages were included in Handmade at Wallspace, New York, and State of Emergence: Unsuspected Cracks in the Art World Infrastructure at Track 16 Gallery, Los Angeles, both in 2005. This is Youngblood’s first museum exhibition.

Essay

By Kianga Ford

Brenna Youngblood's is a whirlwind chronology that moves from straight portraiture to large-scale landscape collage in less than a couple of years. The images of Youngblood's family and friends, prominent in her earliest works, have receded over time and given way to what the artist articulates as issues of ethics and contemporary representation. In Youngblood's current work, these figures have been drawn into a narrative-driven landscape where subjectivity is implied, rather than exploited, in the architectural details and imagined horizons of her dystopic urban scenes.

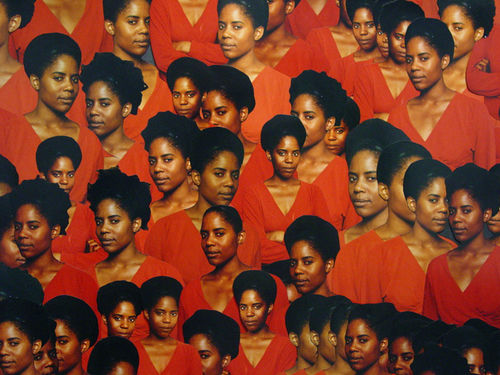

If, as a very young photographer, Youngblood started with an interest in her family, friends, and friends' families, and in the architectural and interior details of their domestic lives—from the embroideries on their cabinets to the chairs in their living rooms—then, in this maturing body of new work, as she herself notes, "the people sort of became architecture."1 In an intellectual double take, she returns to photography to reckon with the question of how one represents already saturated and disregarded figures. She lands front and center in the contemporary ethical struggle over "not using an iconographic image of a black man/black woman" in a medium best known for its capacity to render the body with compelling veracity and for its historical fetishization of just such bodies.

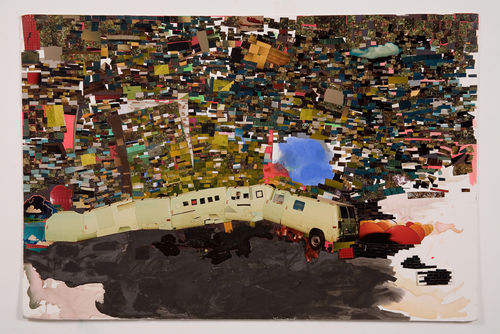

In Youngblood's newest group of works, bricks carefully removed from her archive of domestic images are bricolaged and repeated to make roads and facades and imminent environs; the roads creep up to meet windows stolen (well, borrowed) from architectural images, and the sky is punctuated by the odd letter transposed from a standard advertising circular. In Youngblood's newest landscapes, the photographic document is subsumed in a mélange of urban matter. It is as likely to be present as unexposed old photo paper cum color palette as it is to be an actual detail from the artist's documentary archive. And if the photograph is swept up by the city, this subsumption is repeated formally in its irreversible amalgamation with the tactile bodies of paint and matter. From sprayed to poured, in these collaged landscapes, paint builds up to take on an active surfaceness that resounds with the material and symbolic weight of the city, of blood and asphalt.

The treatment of the figure that appeared in Youngblood's earlier composite portraits of her mother and friends reemerges in a way of seeing the paint itself as "a body to manipulate." A body in a field of bodies, Youngblood's photographs move into landscape and aim to get to something beyond the solitary gesture of the individual in the portrait, beyond representation into a field of gesture(s). In her current project at the Hammer Museum, both the end of this chronology and its foreshadowing are presented. The Army (2005), reversioned for inclusion here, offers an endless proposition of gestural possibilities with a solitary subject.

One of the most arresting of the pieces that make up Youngblood's current body of landscapes is "It's suicide . . . you can't win!" yells Adrian Balboa. "Bla, Bla, Bla," I Reply" (2005). The voice that emerges from this scene is that of -Adrian Balboa, devoted wife of icon-of-the oppressed Rocky Balboa. Overwhelmed by the seeming impossibility of the battle he prepares to engage against Russian destroyer Ivan Drago, Adrian pleads with Rocky to step down. But those of us who know the scene know, of course, that the fight continues and that ultimately, to the satisfaction of a worldwide cinema audience, Rocky prevails. If you know Los Angeles geography, you may recognize the figures that remain in It's suicide as the runners who have finally managed an escape from that mural on the 5 Freeway. In It's Suicide, the runners run on, seeming as if at any moment they might come bursting through the fence that separates them from a new cosmology of almost golden brick roads that drop down just below them and winding around a much-encumbered center of nature that reaches simultaneously for foreboding skies of menacing collaged clouds and these streets of gold. The narrative mining continues in Really, You Shouldn't Have (2006), and—at least for an audience just four months away from the natural and governmental disaster that was Hurricane Katrina—the references of the flowing rivers and ominous orange clouds are direct.

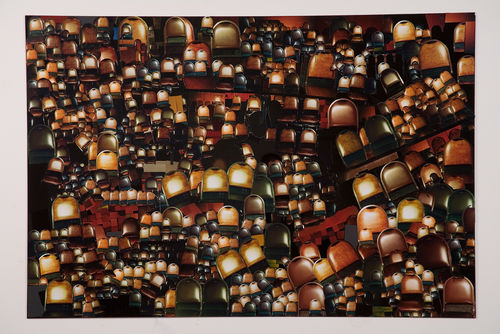

Youngblood describes works such as The Subtle Shift between Then and Now (2005), with its seemingly endless repetition of collaged chairs, and Detail of a Fine Mess (2005), with its echoing lamps, as studies. Like the hooded figures that appear in her exhibition at the Hammer Museum and suggest the engulfing of a figure into a field of fantastic architecture, these studies function as investigations through which both Youngblood and her viewers come to grasp the expanded landscapes of It's Suicide and Really, You Shouldn't Have.

Like much of the art that has fallen under the rubric of a broadly post-black gesture, Youngblood's works are materially and architecturally sensitive innovations that remain deeply concerned with flow, position, people, and relationships. Clearly present is the urban collage work of artists such as Mark Bradford, whose aesthetic proximity, Youngblood would argue, is a function of being engaged in the same conversation. The work, too, has fantastic elements that reveal the spaces and conversations that shares with the boys of Conceptual Popstraction2 and other UCLA contemporaries such as Elliot Hundley. Beyond the contemporary dialogues to which she adds a clear voice, Youngblood presents here a body of work with a broad range of historical citations and interlocutions, from Romare Bearden to Mark Rothko, from William Eggleston to Nan Goldin.

With a finely balanced combination of care and abandon, study and proposition, Youngblood approaches the subtleties of the relationship of the photograph to states of disenfranchisement at precisely this historical moment. She proposes, for now, an endlessly repeatable figure that ultimately recedes into a narrative sustained by its objects and environs.

Notes

1. All quotations from Brenna Youngblood are from an interview with the author, November 2005.

2. The artist of Conceptual Popstraction, a self-generated label, are Amir H. Fallah, Chris Grant, Nathan Mabry, Antonio Adriano Puleo, and Rob Thom. The artist published a book documenting their experiences and the work they produced as students in the UCLA graduate fine art program and participated in a group exhibition of the same title at cherrydelosreyes gallery in Los Angles; see Conceptual Popstraction ([Culver City, Calif.]: Beautiful/Decay, 2004).

Kianga Ford is an artist and scholar. She is a 2003 graduate of UCLA’s MFA program; a doctoral candidate in the History of Consciousness Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz; and an assistant professor in the Studio for Interrelated Media at Massachusetts College of Art.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, Fox Entertainment Group's Arts Development Fee, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.