Hammer Projects: Angela Dufresne

- – This is a past exhibition

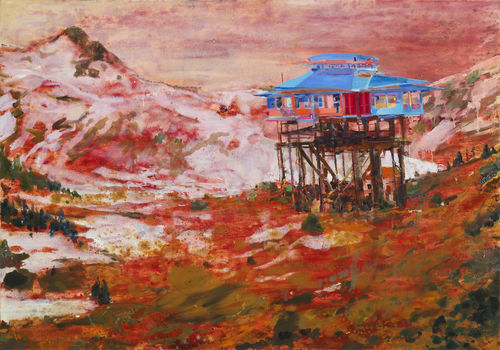

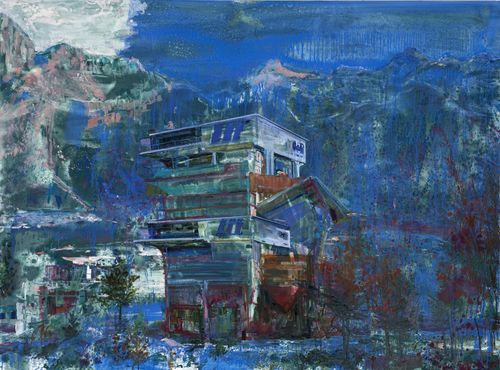

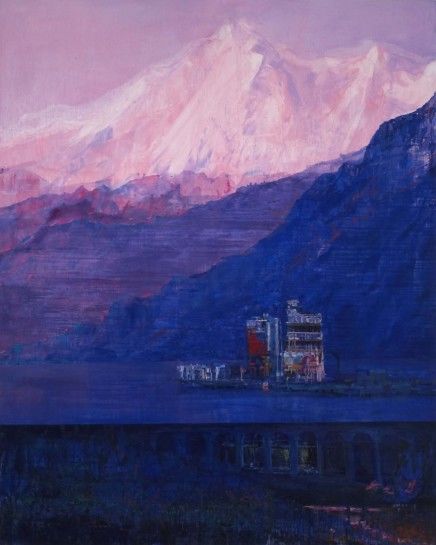

Angela Dufresne's large canvases depict imaginary landscapes populated by strange modernist structures. Dufresne's brushstrokes, painted with a loose, frenetic energy, add to the sense of alienation and anxiety her compositions produce, yet they also translate the forward-looking idealism espoused by modernist architects like Le Corbusier or Frank Lloyd Wright. She presents utopias gone awry in color schemes that range from vivid acidic hues to more natural earthy tones.

Biography

Angela Dufresne was born in 1969 in Hartford, Connecticut, and lives in Brooklyn. She received a BFA in 1991 from the Kansas City Art Institute, and an MFA from the Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, in 1998. Her paintings were the subject of solo exhibitions at Monya Rowe Gallery, New York; Galleria Glance, Milan; and Miller Block, Boston. Her work was included in Greater New York 2005 at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, New York, as well as in group exhibitions at Lehmann Maupin and LeLong Gallery in New York. Writings on her paintings have appeared in Interview magazine, the New York Times, and the Boston Globe. This is Dufresne's first solo museum exhibition.

Essay

By Nicole Rudick

A prolific and versatile painter, Angela Dufresne produces large-scale landscapes that contain the collaged effect of rectilinear modernist buildings inserted into rough, time-swept landscapes—all rendered in a painterly collision of color. In this single breath, Dufresne rewrites the context of form and space, creating her own branches of history and infusing them with a Romantic mood and a sense of personal freedom.

Dufresne's interest in creating places that could have existed (or may yet—some of her titles are postdated) began with her self-described "bastard portraits," in which she invented unlikely identities (she once suggested the progeny of Julia Child and Kris Kristofferson). This impulse to distort history, thereby creating new meaning, extends to Dufresne's work with architecture. A 2004 canvas titled Me and Bruce Lee and another famous yet unnamable man on the shore in front of an unmade building by Frank Lloyd Wright called the Donahoe Triptych pictures a majestic modernist construction, alternately arched and cubed, spanning three rocky outcroppings high above a dark, blue sea. Backlit by a hazy dusk sky, Dufresne's "realized" building is based on a drawing made by Wright but never built. Here she fuses the idea of invented relationships (the figures of the title are barely visible in the panoramic setting) with a piece of architecture that is both real and not. Dufresne makes Wright's visionary, heroic design tangible so that it can serve as the ideal receptacle for her imaginative exploits.

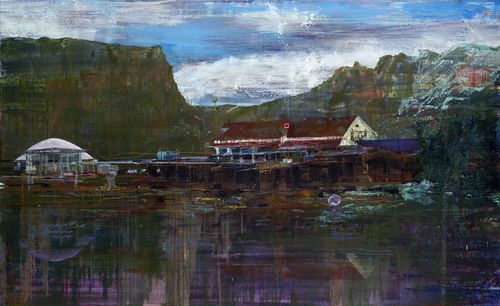

In her most recent paintings, Dufresne exercises the limits of subjectivity by "shoplifting" from various time periods. In The Oum kaltheum International Center for Vocal and Intellectual Training built on the Remains of the Congress Building in Brasilia, Brazil. Designed by Brian Burton (aka Danger mouse) c. 2052 (2006), she combines the mountainous terrain of Washington State with the white, sensuous curves of Oscar Niemeyer's Brazilian construction. The latter's pale, overturned bowl is in ruins, overlaid with a no less aged yet more recent wooden barn and dock. The quiet repose of the buildings in their verdant setting and their still reflection in the dark waters of the lake provide a meditative vista. The displacement of South American architecture to a mismatched topography and the physical layering of buildings not only suggest an organic relationship between disparate styles but also, in the same turn, propose a new and very real, if irrational, aesthetic sensibility. Dufresne does not invent wholly fantastical worlds; rather, she pulls places and things from history's storehouse, rooting her paintings in a fragmented reality. The resulting dual character of the composition—its simultaneous strangeness and familiarity—suggests that the artist has experienced a sort of vision, in which the inner world (her subjectivity) and the outer (in this case, specificity of architectural purpose and form) can be harmoniously united. As such, Dufresne's paintings function through feeling, falling midway between thought and gesture.

This temporal and physical compression stems both from Dufresne's abiding fascination with film and from the additive nature of her process. She has focused by turns on the work of such directors as Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Joseph Losey, and John Cassavetes—all of whom variously focused their lenses on emotional instability, outsider status, and impossible heroes. Dufresne watches not just a selection from each oeuvre, however, but consumes nearly the entirety of each director's body of work. This deep immersion becomes a breakneck montage, permitting an overlap or blurring and condensing each director's themes and styles and abetting her interest in distortion. The contracted ideas then serve as filters, through which she begins to explore notions of isolation, melancholia, and displacement. These qualities are readily in evidence in her portraits, which are derived from film stills. Typically depicting women (Anna Magnani, Jeanne Moreau, and Charlotte Rampling, for instance) in moments of pensive stillness, the intimate paintings elicit no narrative but rather utilize pure mood, often a seething vulnerability, as a means of expressing thought and emotion. On a grander scale, The First Frame from Mildred Pierce with the beach house Renovations Including a View of the Michael Curtiz/Rainer Werner Fassbinder Observation Deck (2006) transfers the noir tone of James M. Cain's story to canvas: drenched in a murky blackness, the work is lightened only occasionally with pale shadows of rising hills punctuated by electric orange dots of light and the ghostly outline of an imposing house set in the foreground. Though she draws here on the pictorial modes of film, Dufresne again excludes artificial plotting and opens up the painting to emblematic emotion.

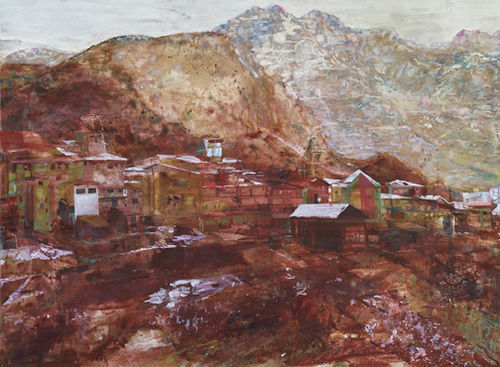

In a similar rejection of narrative, Dufresne originally referred to her landscapes as "stills" but realized the inaccuracy of this term: "It's impossible. A painting is not a still because there's all this time that passes in the process of making it. . . . I revisit it at different times, so it goes through multiple interpretations."1 This sense of layering boasts timelessness and simultaneity, which first come through in her work by way of color. In The Rhine—The Culinary Row Academy and Conservatory Institute (2006), as in much of Dufresne's color-saturated work, the underlayer of paint shows through the secondary hues added to define objects. Citing Jan Vermeer's and Edouard Vuillard's modes of color mixing as an influence, Dufresne intentionally pushes the base color and additive layer together through thin strokes of paint (in this case, a mossy green and reddish brown, respectively; in other paintings, the colors are more at odds, such as oversaturated red and purple), at once permitting an atmosphere of transparency and a balanced thematic mood.

On another level, the painting depicts an example of social reversal, showing a castle transformed from a residence of the wealthy to a cooking school and a grouping of small buildings that once housed servants and now act as restaurants. Helped along by Dufresne's fine washes of paint, however, the scene can also be read as a two-dimensional landscape flattened up against the picture plane—a single wall of color and abstracted form. As such, the various horizontal elements work as strata of sky, earth, and roots (in which the "old way" of class becomes "buried" at the base of the canvas). They also imply a temporal passage: Dufresne essentially moves social organization forward in historical time while also thinking about it retrospectively (she first displaces class and then does away with it completely). Denying her role as a social critic, Dufresne instead advocates a reading of her work in terms of celebration and freedom. When a building is recouped—as the castle is in this painting and as all her buildings are—it takes on a new purpose, a new context, and, in the artist's words, "comes alive." Loosening reality from the bonds of reason and aligning it with the freedom of experience and imagination, Dufresne imbues it with profoundly new meaning—passionately, and sometimes convulsively, unleashing a new conception of the world.

Notes

1. All quotations from Angela Dufresne are from an interview with the author, June 2006.

Nicole Rudick is assistant editor of Artforum and managing editor of Bookforum.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Fox Entertainment Group's Arts Development Fee, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, members of the Hammer Circle, and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.