A Fine Experiment: A Tribute to Robert Heinecken

- – This is a past exhibition

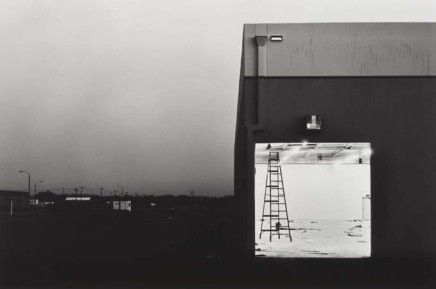

Robert Heinecken (1931–2006) left a significant mark on the world of photography, as an artist, teacher, curator, and collector. While forming the department of photography at UCLA, he had the foresight to build a resourceful photography collection for his students at the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. This exhibition celebrates Heinecken and his collection of works by such artists as Walker Evans, Imogen Cunningham, Garry Winogrand, Heinecken himself, and many of his students.

This exhibition was organized by Carolyn Peter, director of the Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, and former associate curator at the Hammer Museum.

Essay

By James Welling

UCLA Professor Emeritus Robert Heinecken died in May 2006 at the age of 74. Heinecken took over UCLA's photography course offerings in 1960 and for the next 33 years he presided over an extraordinary group of students and visiting faculty. Over these years, through his work and his teaching, Heinecken helped to transform the way we think about photography.

Heinecken was also instrumental in nudging UCLA, under the auspices of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, at the Frederick S. Wight Gallery—the Hammer Museum's predecessor—to collect contemporary photographs. So it is fitting that A Fine Experiment, astutely curated by Carolyn Peter, honors both Heinecken and the work he helped acquire for the Grunwald Center—the work of established photographers, peers, and former students.

Robert Heinecken was one of the first photographers to make extensive use of appropriated imagery. And many commentators noted he rarely used a camera.1 Like a ventriloquist, he threw his voice into many types of found images.

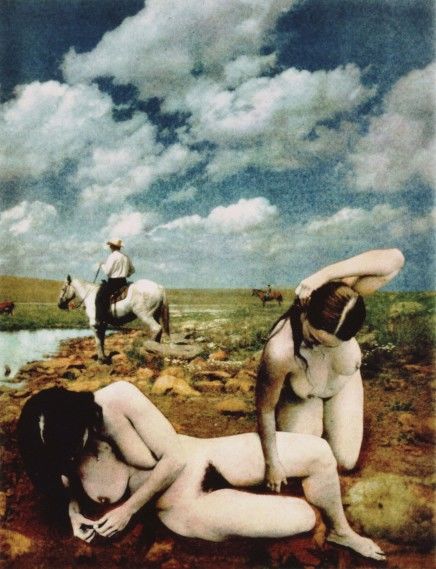

In an essay on Heinecken written in 1976, abstract photographer and colleague Carl Chiarenza wrote: "He uses existing photographs ... and their reproductions because they have littered the world and our minds with unlimited examples of every conceivable image of truth, beauty, banality, eroticism, brutality, pornography, consumerism, political idea, personality, idol, and ideal. Indeed one is hard put to name anything that has not been replaced by a photographically derived image. His recycling of these images makes this astounding point before making any other."2

By selecting and reprinting preexisting imagery, Heinecken developed an elegant and economical strategy for exploring various American cultural obsessions: war, sex, and food. He created images by contact printing pages of mass-market magazines so that both sides of the magazine page are superimposed. Anticipating the work of image appropriators Martha Rossler, Richard Prince, Silvia Kolbowski, and others, Heinecken (along with his peers, John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, and Andy Warhol) ushered postmodernism in with a bang. That photography is now on an equal footing with painting and sculpture, video and performance art is, in no small part, due to Heinecken's groundbreaking work.

While photography was making its way into the art world, its historical interpretation over the past 20 years was undergoing a radical simplification. The wonderfully varied (and messy) history of photography from the 1890s onward was suddenly streamlined into a series of concise bullet points. Eugène Atget became the father figure for all of photography. August Sander and Walker Evans, both "classifiers" (like the conceptualists), formed the next chapter. Then came the conceptual document, then the cinematic (narrative), and finally recent German photography (returning to the "objectivity" of Sander.)

While I find virtually all the photography in this history extremely important and inspiring, I fear significant work has been overlooked, in particular that which addresses the materiality of the photograph.3 One of the ironies of history is that while Heinecken is credited with giving birth to the postmodern episteme, postmodernism and the art world have, for the most part, ignored the questions of process and material specificity that underlie Heinecken's work. This has led to a new kind of photograph, which, in spite of its large size, remains immaterial. A face mounted behind a plastic laminate, it is a transparent screen through which stories are told, very much like cinema.

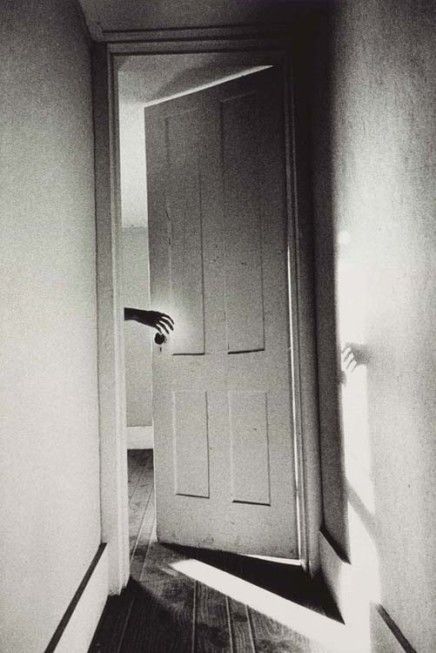

On the other hand, photographs which emphasize materiality, as much of Heinecken's work did, force the viewer to address not only the narrative subject but the means and matter comprising the photograph, its matte or glossy surface, its sharp or fuzzy or grainless texture, its relative size and shape, how it is put on the wall, if it's even on the wall.

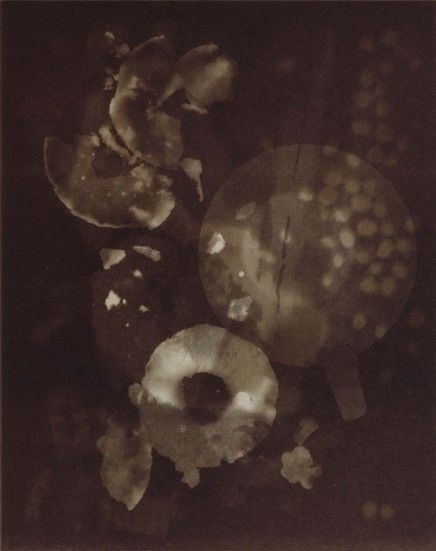

Robert Heinecken and the artists of A Fine Experiment were all for materiality, all for underlining the thing-ness of photography. Most of Heinecken's work consisted of photograms, exposures made on photographic paper without a camera. In addition to being the simplest form of photography, the photogram is probably the most literal example of the photographic process.

Consider two Heinecken photograms made within a few years of each other. Untitled, from 1971, is a suite of photograms produced by scattering donuts on photographic paper. It wittily addresses both the materiality of breakfast and the surface of the photographic support. In No Cal, 1967, from his classic Are You Rea portfolio, Heinecken printed a magazine page onto a sheet of photo paper, superimposing the image of a woman over a low-calorie beverage. In these two works Heinecken's embrace of process, with its erotic eruptions and ribald humor gives the work an outré quality that still somehow manages to stun us. And the photographs he helped to add to the collection generate a similar kind of excitement over the processes of making a photograph.4

In the mid 1960s Heinecken wrote: "There is a vast difference between taking a picture and making a photograph."5 This distinction is probably most clearly articulated in a work Heinecken made on January 20th, 1981, when he pressed an 11 x 14–inch piece of Cibachrome paper to a small color television set as Ronald Reagan gave his first inaugural address.6 The resulting image, a blurry "videogram," in Heinecken's idiosyncratic terminology, embodies this tension. A photograph of Reagan is there for the taking, if only you get off the sofa with the smarts to make it. Out of photography's intractableness, Heinecken's blurry image of Reagan, one part machine, two parts sleight of hand, breaches this dichotomy.

Notes

1. He was, as Arthur Danto noted in 1999, a "photographist," not a photographer.

2. Carl Chiarenza, "Robert Heinecken 1931–2006," August 12, 2006. University of California, Los Angeles. Unpaginated pamphlet. See also www.heinecken.org for colleagues' and students' memories of Heinecken.

3. Pictorialist photography at the turn of the century, much modernist photography between the wars, all subjective photography of the 1950s, all abstract photography throughout the century, are some of the overlooked practices.

4. A list of some of the processes, materials, and cameras used in A Fine Experiment reads like a grand catalogue of photography's means: offset lithograph, dye transfer print, Polaroid print, gelatin silver print, Cibachrome print, color-in-color print, photogram, photo collage, double exposure, cliché verre, contact print, large format, panoramic, 35 mm camera.

5. Chiarenza, Ibid.

6. Inaugural Excerpt Videogram/Ronald Reagan, (...of others were called...), 1981.

James Welling is an artist and professor in the UCLA Department of Art.