Hammer Projects: Phoebe Washburn

- – This is a past exhibition

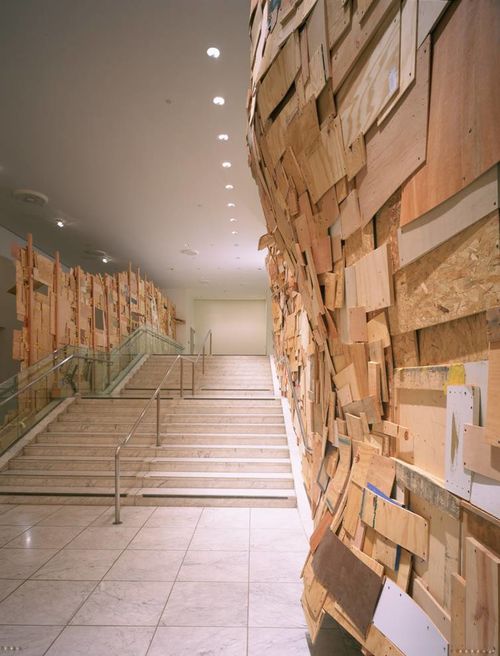

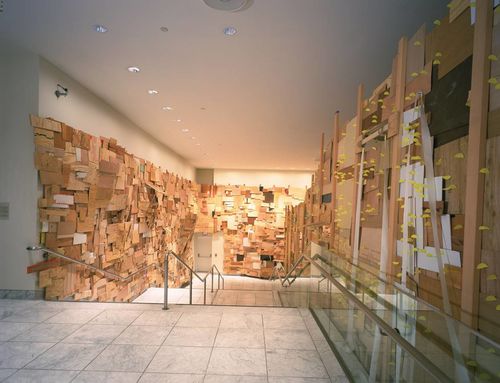

Phoebe Washburn's sprawling installation, It Has No Secret Surprise, fills the Hammer Museum's lobby walls with a composition of thousands of pieces of found, scavenged, and purchased pieces of cardboard or plywood cut into varying lengths and widths. Washburn’s site-specific work addresses ideas of environmental sustainability and notions of recycling, trash, and landscape. Materials for each piece are collected over time and built up in a slow, seemingly organic process to resemble topological maps, urban landscapes, or the fine layers of shells.

Biography

Phoebe Washburn was born in 1973 and currently lives in New York. She received her M.F.A. from the School of Visual Arts in New York and her B.F.A. from Tulane University in New Orleans. Her work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions in the United States and Europe, including solo presentations at the Rice University Gallery in Houston and LFL Gallery in New York. Her work was also included in Greater New York at P.S.1. in New York, The Bench at the Kunsthalle St. Gallen in Switzerland, and Make It Now at the Sculpture Center in Long Island City, New York. Washburn's work has been reviewed in Art in America, Artforum, Flash Art, The New York Times and The Village Voice.

Essay

By Ana Finel Honigman

Phoebe Washburn makes the most poetic case for recycling since Italian author Italo Calvino's description in Invisible Cities of an immaculate urban paradise where all once-used items are immediately discarded in putrid, sprawling wastelands, ominously swelling outside city limits. Instead of allowing rubbish to pile up, away from view, Washburn brings our exhausted and abandoned trash inside. The New York–based artist redeems our refuse by building enormous architectural, topographical, or organic-seeming sculptures out of bits of boring junk. As she has said of her collecting ethos: "I select objects that have already been worn, already marked and already discarded because then they are already in the state I want them to be. They are what they are already."

Every day she collects scraps from construction sites and armloads of office waste. She culls her materials—including masses of collapsed cardboard boxes, newspapers, and wood chips—from local loading docks, alleyways, and recycling bins. She then organizes, stacks, binds, and nails together her prosaic discoveries. In the process, she combines the chaos and fortitude of an urban pack rat scavenging New York's streets for intriguing items with a dedicated city manager's need to tidy up our civic mess.

Unlike other artists known for scrounging, hoarding, and recontextualizing found objects deemed unremarkable or undesirable—such as Katie Grinnan, Thomas Hirschhorn, Dieter Roth, Jessica Stockholder, and Sarah Sze—Washburn does not scour the streets for eccentric or personal treasures. Instead she selects dreary artifacts from our tightly organized bureaucratic culture. While ideas about individuality and subjectivity dictate Roth's idiosyncratic assemblages of odds and ends or Stockholder's monsters made from domestic machinery, Washburn's raw materials are unassuming and uneventful throughout their functional life spans.

After graduating from the MFA program at Manhattan's School of Visual Arts, Washburn had her first solo show at New York's LFL Gallery in 2002. There she built Between Sweet and Low, a twenty-five-by-seventeen-foot swirling vortex of cut cardboard screwed into form with four-inch drywall tacks. In October 2002 at the Rice University Art Gallery in Houston, Texas, she presented a mammoth installation entitled True, False, and Slightly Better. This heaving tidal wave of pressed boxes, colored with dainty shades of rejected hardware store paint, appeared to be bolstered by buckling plastic folding chairs and frail wood ladders. These inadequate structures seemed to have been frantically forced underneath the precarious mass in a desperate, temporary attempt to restrain it, but viewers who trusted its stability could climb up and spot empty containers for screws, sacks of cement, builder’s wax pencils, and rolls of duct tape, which seemed to have been helplessly swept up in the voracious tornado-like twist.

In September 2004 Washburn brilliantly focused on the global and social, not only the local or ecological, ramifications of waste and recycling with Nothing's Cutie at the LFL Gallery, a shantytown of sawed-off wood construction beams painted in pastels, which crowded toward the gallery's entrance and spanned the exhibition space. The mini city's limits were marked by a “Hello” pasted in gaffer's tape on one of the gallery's high beams and a bucket with “The End” written with Phillips-head screws embedded in excess sawdust. Between these borders, an entire infrastructure infested the gallery interior. Scaffolding upheld clusters of wood slats that curved around the gallery's cement construction beams, while dense hills and rivers of sawdust divided neighborhoods. Washburn's cityscape was an elegant and playful microcosm of devastated neighborhoods across the world where need and ingenuity compel impoverished city dwellers to construct homes from metal sheets, worn canvas, weak wood and other materials easily discarded by more affluent urbanites.

In the Hammer Museum's long, high-ceilinged entrance lobby, Washburn has aligned sheets and squares of found scrap wood, which forms a surrogate wall that curves and warps like an undulating wood patchwork quilt, while the wall behind it remains blank. Housed within the structure is a space where Washburn has planted seedlings, which boldly grow alongside the ravished wood. The presence of the little plants poetically highlights how she has revived the wood by putting it to use, instead of letting it rot as waste.

Unlike the bureaucrats who dictate how trash is dealt with or the craftsmen compelled by purely practical concerns to select one object over another, Washburn considers herself, as an artist, "an anti-builder builder." She is like the paper pushers whose pointless office tasks produce her raw materials in that repetition guides her process; she and her assistants let the spaces where she works determine the installation's general parameters, but they allow their materials to grow and thin without any organized plan. "It sounds silly," Washburn says, "but we are like beavers just building and building, letting the action take precedent over any predetermined design."

At the Hammer, more than in previous installations, Washburn's renegade materials are restricted and regulated by fire codes and considerations of the space's function as an entryway. "The lobby is different from a gallery's clean, hermetically sealed interior," she explains, "I needed to telescope my practice down into the space. It couldn't spiral out and take over as usual. It had to remain contained." Yet the structure still appears ominous, even as it politely hugs the wall. Despite being pared down, her materials seem to have an unwelcome presence in the previously pristine space, serving as a reminder that art ought to confront and engage what “productive” society ignores or denies.

By making art from objects that most often act as facilitators for our routines or accessories to our most mindless activities, instead of fodder for our fantasies, Washburn undermines the romantic notion that art is a renegade act separate from the materials and mentality of our office-run culture. Often conscientious pack rats temporarily house the refuse she reuses in the hope that spare boxes and extra tape will eventually come in handy. Months after a move, before one becomes sufficiently settled in, packing boxes and twine still appear useful. Then these potentially practical items are discarded before they can earn their place in office supply rooms, dorm closets, or the basements of new houses, but while they remain in storage, they signify transition. Similarly, Washburn's installations simulate the transition we, like the inhabitants of Calvino's imaginary city, are in as we passively shift from maintaining order to being subsumed by our messes and excesses.

Ana Finel Honigman is a critic and PhD candidate in the history of art at Oxford University.

Hammer Projects are organized by James Elaine, and are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.

Phoebe Washburn's Hammer Project received additional support from Stavros Merjos and Honor Fraser, Sherry and Douglas Oliver, Susan A. and James N. Phillips, and Kay and Marc Richards.