Hammer Projects: Paul Chan

- – This is a past exhibition

Paul Chan’s 17-minute digital animation, My Birds…trash… the future (2004), begins with Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and encompasses the Bible, Goya, and Blake. Projected on both sides of a long, narrow screen, rendered in eye-popping acid colors (or acid-popping colors), and peopled with a panoply of characters including the late rapper Biggie Smalls and the filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, the piece is an ambiguous tale of political horror and modern alienation.

Biography

Paul Chan was born in 1973 in Hong Kong and currently lives in New York City. He received his BFA in video and digital arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and his MFA in film, video, and new media from Bard College. His work was included in the 2004–5 Carnegie International at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, and has been shown at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. His work will be shown at the eighth Biennale d’Art Contemporain in Lyon, France, in fall 2005.

Essay

By Johanna Burton

“Utopian desire and unspeakable violence are not mutually exclusive.” Words delivered by Paul Chan in a recent interview, these could stand as a credo for the artist’s work as a whole and are succinctly embodied in his My Birds...Trash...The Future. A two-channel, seventeen-minute animated video projection, My Birds... improbably pairs not just fantasies of utopia with realities of violence but also Samuel Beckett with the Bible, the filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini with the rapper Biggie Smalls, and low-tech contemporary pop-up advertising techniques with arguably outdated traditions of history painting. Presented on a floating, wood-framed, double-sided screen, the piece occupies an aggressively hybrid status, whereby various vernaculars culled from television, the Internet, film, indie comics, and military-training tools coalesce in a bleakly cacophonous human drama at once alien and all too familiar.

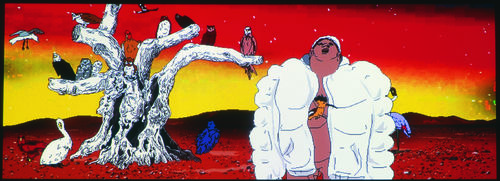

My Birds... comprises a loose adaptation, update, and merger of the sparse stage set from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot as layered with the fire-and-brimstone doctrines (and taboos) dictated in the book of Leviticus. One need only refer to the set specifications outlined in the great modernist playwright’s famous “tragicomedy in two acts,” written in 1948, to trip onto clues about Chan’s inspiration for his own ambivalent staging. Act 1, as described by Beckett: A country road. A tree. Evening. And act 2: Next day. Same time. Same place. A similarly timeless, placeless, seemingly hopeless breed of landscape is evoked by Chan, though his own vehemently allegorical site presided over, like Beckett’s, by a gnarled, barren tree is ultimately cluttered by the effects and affects of recognizably historical and contemporary debris. Further, in place of Vladimir, Estragon, Lucky, Pozzo, and the nameless “boy,” Chan populates his own space of perpetual unfolding with, among others, a flock of ominous birds of all varieties, a single swooping bat, some desperate dogs, several type A suicide bombers, and the animated likenesses of two figures infamous for (and here united by) their mysterious, brutal, and untimely deaths: Pasolini and Biggie Smalls.

Whereas Beckett’s two acts were necessarily played out one following the other, Chan’s are staged simultaneously, projected recto-verso on a long, nearly sculptural horizontal screen, and thus they are quite literally connected by the very fabric that holds them apart. The front side is given over to Beckettian leanings and longings, while the back is tethered more fundamentally to the sacrificial rites born of the book of Revelations (with black hellfire clouds abounding), but like the infra-thin screen they share, the two sides ultimately iterate a single landscape, the blurry line between them suggesting a similar lack of easy distinction when it comes to such ostensible opposites as cruelty and compassion or pain and pleasure. Forced to walk from one side to the other in order to see both halves of the video projection, viewers are invited into a phenomenological and mnemonic situation that actualizes the two versions of limbo offered by Chan—one can never see the whole piece at once but is always drifting between its sides, just as aware of what can’t be seen as what can. As the audience perambulates the space around the screen, the panoply of Chan’s characters similarly traverse its dimensions—Biggie Smalls, Pasolini, and the others nomadically drifting from one side of the screen to the other in order to engage whatever hapless situation they find waiting for them.

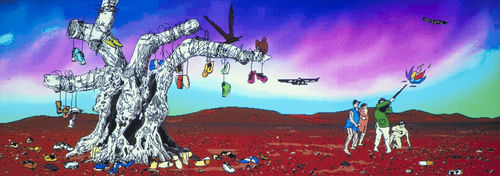

If the connection between Chan’s textual referents and his roster of diverse players appears less than transparent, the activities they engage in together are no less immediately revealing (as long as rational explanations are what we’re after). The assortment of characters variously rape, maim, cannibalize, and terrorize one another, playing out rituals of cruelty that, due to recent political events, are in the process of becoming translated into increasingly normalized, regularly circulated images. A grating sound track composed of tinny hip-hop cell-phone rings, pulsing car alarms, and mechanized birdcalls accompanies the mayhem, bringing every action to a kind of sustained, though anticlimactic, peak. The ultraflat, techno-futurist graphics and acidic, jarring palette used for My Birds... deliver a similar rub, at once awful and awing.

Largely horrific images speed by, hard to grasp, harder to let go of: safety orange–clad hunters shoot down enormous birds, which lie writhing in their own blood; Beckett’s tree becomes Goya’s, hung with the bodies of humans and a dog; naked paparazzi (including one amputee) attempt to take photographs from the safety of a Hummer while a vulture struggles to keep them at bay; a man on all fours wolfs down the remains of a dead bird; a William Blake–inspired couple embrace, slumping together into sex or death or both, emitting not words but instead ominous mathematical equations. The mean, raw, deeply desperate nature of these activities and the artist’s intentionally discordant manner of presenting them reflects Chan’s interest in addressing contemporary political, ethical, and aesthetic woes by absorbing and redirecting certain of their elements. Fond of Bertolt Brecht’s idea that, to attempt any kind of resistance, one should “start not from the good old things but from the bad new things,” Chan’s invocation of Beckett and even the Bible lands him squarely in contemporary terrain due to the visual and aural languages he employs.

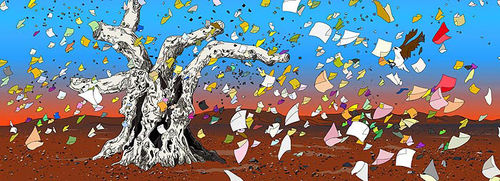

Perhaps, given the high doses, it is easier to see unspeakable violence than utopian desire in My Birds... Yet the artist’s reminder that the two are not mutually exclusive hardly means that they are found in equal, or even relative, abundance. By taking up Waiting for Godot and Leviticus, Chan focuses on two texts that, in very different ways, detail the effects of lost faith but simultaneously—if delicately—defer the loss of faith altogether. Indeed, these are works that, however wretchedly, document the persistence of faith despite the loss of reassuring objects. Chan’s claustrophobic slew of images reveal these hidden possibilities in brief moments of unexpected silence and poetic, melancholic imagery. At one point, a windstorm carries a vast tumble of litter across an otherwise unpopulated scene, its swirling colors abstractable into a pure dose of nearly spiritual pleasure or, alternately, read as utter desolation, the end finally come. It is in the or between those possibilities that Chan’s work operates. After all, the first line of Waiting for Godot, spoken by Estragon to Vladimir, is “Nothing to be done,” but they keep on doing anyway.

Johanna Burton is an art historian and critic living in New York City.

Hammer Projects are organized by James Elaine, and are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.