Fair Use

- – This is a past exhibition

Fair Use: Appropriation in Recent Film and Video features works by Candice Breitz, Omer Fast, Christian Jankowski, Les LeVeque, Matthias Müller, and Eddo Stern on video monitors in the Hammer Museum’s lobby gallery. Presenting varied strategies of appropriation and sampling in film and video from the last decade, Fair Use explores the exceedingly prevalent redirection and alteration of existing media. These processes resonate in work by artists who treat media as raw material and who turn the tools and products of information distribution against itself.

Fair Use is a thesis exhibition presented by Matthew Thompson for the Master of Arts in Critical and Curatorial Studies, UCLA Department of Art, in conjunction with the Hammer Museum. Support is provided by the Ruth Peskin Distinguished Artists Fund.

Artists

- Craig Baldwin

- Candice Breitz

- Omer Fast

- Johan Grimonprez

- Christian Jankowski

- Les LeVeque

- Matthias Müller

- Brian Springer

- Eddo Stern

Essay

By Matthew Thompson

The use and alteration of preexisting images from mass media, a pervasive technique within contemporary art, has become exceedingly prevalent in film and video work. More than simply remixing and manipulating their sources, artists are actively engaging in the appropriation and inhabitation of media forms such as newscasts, live call-in shows, commercials, video games, Hollywood narrative cinema, and found amateur footage. Finding analogs in practices that occupy the sites they seek to contest—computer hacking and graffiti being two examples—the resulting works turn a strong preexisting infrastructure to their own use. And, more often than not, the sampled material is redeployed in a manner that subverts its original purpose or context.

In this sense, the term appropriation connotes a turn away from the appropriate. In legal terms, “fair use” refers to the right to use copyrighted materials for educational or noncommercial purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Other factors that determine whether a use is fair include the nature of the copyrighted work, how substantial the portion used is in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole, and whether the use would have any impact on the market for the copyrighted work. Although one could argue that the use of preexisting material in the films and videos presented in this exhibition is fair, many copyright experts believe that the concept of fair use has little practical relevance in a society in which the fear of costly litigation compels many to seek permission before using any portion of a copyrighted work.

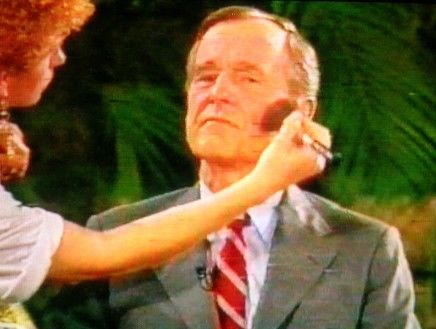

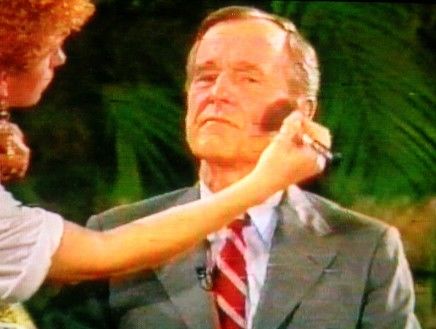

Most of the preexisting works sampled by the artists in the exhibition were created within institutional frameworks that lend them a certain authority: we recognize news reporting as legitimate, for example, because we see it on a news broadcast issued by a news network. A playful manner of negotiating these institutional structures and an examination of the function and use of media unite the varied tactics of quotation presented in Fair Use. Craig Baldwin’s Sonic Outlaws (1995), for example, is both constructed by and documents techniques of appropriation and the phenomenon of “culture jamming,” the collection, alteration, and redistribution of pieces of mass media for subversive purposes. Another documentary film included in this exhibition, Brian Springer’s Spin (1995), collects satellite feeds of TV personalities and politicians in front of a live camera with open microphones before they go on air and again during commercial breaks. Springer’s film unmasks the broadcasts, showing politicians being made up, covering up, and discussing their preferred prescription drugs.

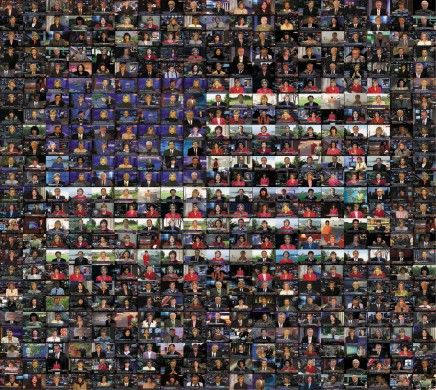

For CNN Concatenated (2002), Omer Fast compiled a ten-thousand-word database from recordings of newscasters and commentators on CNN, then rearranged the spliced words into existential monologues that are directly addressed to the viewer. CNN Concatenated becomes a mesmerizing, darkly humorous questioning of the viewer’s psychological state and agency within a media-saturated environment. Candice Breitz’s Soliloquy Trilogy (2000), a condensation of three blockbuster films into only their respective stars’ speaking parts, employs similarly jarring editing to deconstruct the pure, iconic presence of celebrity. Stripped of narrative cohesion, these strings of utterances verge on the psychotic, held together only by our recognition of the star. CNN Concatenated and Soliloquy Trilogy share a sense of mischievous reworking, wherein lies both the subversive potential of play and what Michel de Certeau describes as “a pleasure in getting around the rules of a constraining space.”1

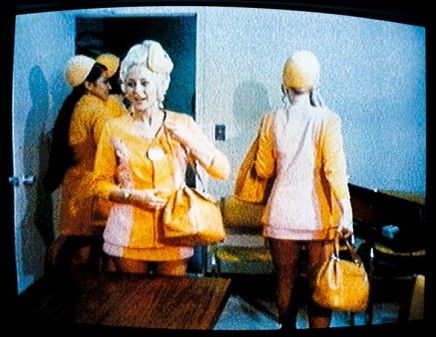

This playful subversion is upended in Christian Jankowski’s Telemistica (1999). In this video, the artist phones in his insecurities about the upcoming Venice Biennale to Italian television psychics. By inserting himself into the televisual stream, Jankowski enters into the productive apparatus. His loop of doubt and reassurance literally plays itself out on television.

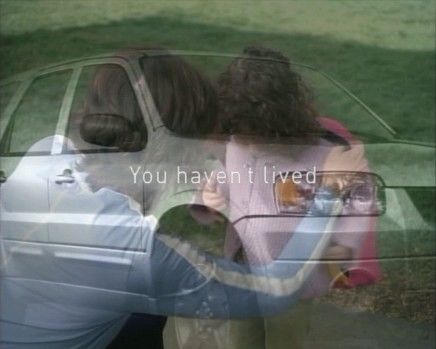

The unsettling perceptual effects achieved by the abrupt edits of CNN Concatenated and Soliloquy Trilogy are pushed to their limit in Les LeVeque’s frame-by-frame weaving of television commercials. In pulse pharma phantasm (2002), nine different pharmaceutical commercials are wrought into a psychedelic strobe of anxiety and relief. Autocraving 15 (2003) subjects car commercials to a similar reworking. In both videos the trancelike fluttering of the frames creates a visual excess that subverts the mechanisms of desire at work in commercial advertisements.

The writing of history is bound up with mass mediation and the problematics of visual representation. In Vietnam Romance (2003), for instance, Eddo Stern has pieced together a narrative from war video games, constructing what he terms a “fictional documentary.” These simulations—increasingly used to train soldiers and militarize youth—are cut, spliced, and inverted to interrogate our complicated relationship to military intervention. In Johan Grimonprez’s dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997), the emergence of skyjacking in the 1960s and 1970s becomes a lens through which to examine the media's obsession with disaster and the ways it shapes reality and history. Matthias Müller explores similar territory in his brooding and poetic meditation on Brasilia. Vacancy (1998) interweaves vintage home movies of the construction and opening of the new city with contemporary footage taken by the artist. A flying helicopter from a 1960 amateur film is seamlessly matched with a moving shadow from shots taken by Müller in 1997.2 This temporal collapse creates a melancholic sketch of the deserted, skeletal city and reveals the uncanny stasis of arrested utopias.

The proliferation of technology that makes simulcasting and deep connectivity possible has also dramatically increased access to the technology of media production. While these technologies have exploded practices of appropriation, to see only their explicit expression in artwork reduces them to architecture. Rem Koolhaas’s equation “technology + cardboard = reality,”3 which he posits as the curse of the architectural profession, reveals a similarly narrow outlook. For the artists in this exhibition, technology is less an armature for their work than a tool among many others, one befitting their site of inquiry. Thus, technology is expressed implicitly, in changes in artistic practices and orientations toward the artistic field. In a similar manner, technology has also altered our relationship to copyrighted material, as evidenced by the popularity of peer-to-peer file-sharing networks. That the music, motion picture, and commercial software industries have lobbied to rewrite the law to maintain control over increasingly evaporating territory should come as no surprise.

Notes

1. Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 18.

2. Kathrin Becker, "Beyond and Back," in Matthias Müller: Album (Frankfurt: Revolver, 2004), 31.

3. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 42.