Hammer Projects: Tara Donovan

- – This is a past exhibition

Tara Donovan’s sculptures are born of everyday materials such as scotch tape, drinking straws, paper plates, and Styrofoam cups. Donovan takes these materials and “grows” them through accumulation. The results are large-scale abstract floor and wall works suggestive of landscapes, clouds, cellular structures and even mold or fungus. She considers patterning, configuration, and the play of light when determining the structure of her works but the final form evolves from the innate properties and structures of the material itself. In her words, “it is not like I’m trying to simulate nature. It’s more of a mimicking of the way of nature, the way things actually grow.”

Hammer Projects are curated by James Elaine.

Biography

Tara Donovan was born in 1969 and lives in New York City. She received her M.F.A. from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1999. Recently she has had solo exhibitions at Ace Gallery, New York and Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland; Akira Ikeda Gallery, Berlin; and the Corcoran College of Art and Design’s Hemicycle Gallery, Washington, D.C. Group exhibition venues include Cooper Union, New York; Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusets; and Weatherspoon Art Gallery, University of North Carolina, Greensboro. In addition, her work was included in the 2000 Whitney Biennial. Articles on Donovan’s work have appeared most recently in the Village Voice, the New York Times, Artforum, and W.

Essay

By Paul Brewer

Tara Donovan’s work is easily recognized as a descendant of various legacies associated with the transposition of utilitarian materials. In stretching the contextual boundaries of the gallery to accommodate the rebirth of common manufactured objects, Marcel Duchamp’s scandalous “readymades” opened a veritable floodgate. Many artists quickly exploited the newfound opportunities his conceptual formula provided and, in so doing, formed a lineage of resonant practices contingent upon the relationship of art to everyday life evident in nearly every movement leading up to the defining plurality of contemporary artistic production.

The investigations of Process, Minimalist, and Postminimalist artists—led by Eva Hesse, Robert Morris, and Richard Serra—are consistently cited by critics and the artist alike in discussions of Donovan’s work. The same goes for contemporary artists such as Tony Feher, Tom Friedman, Tim Hawkinson, and Sarah Sze, all of whom share a concern with disposable artifacts expelled by the frenzied machinations of capitalism. Certainly, in categorizations of media and process, innumerable associations and affinities such as these can be supported, but in an actual encounter with Donovan’s work, other precedents situating themselves firmly in the arena of perception intermingle to dramatic effect. It is from the endowments of artists such as Robert Irwin and James Turrell, who so affectingly demonstrate our primal connections to light and space, that Donovan prodigiously borrows an adherence to the guiding principles of phenomenology.

Donovan enters into an analytical dialogue with a singular, minute, and mass-produced material regarding its physical properties in order to tease out structural possibilities that flaunt phenomenal visual behavior, which is then amplified through the intense labor demanded by her ambitious strategies of accumulation. It’s a reciprocal discussion that galvanizes an unpredictable potential in the material through coercive experimentation. While an analogy to chemistry is not unwarranted in relation to Donovan’s process, she has no real investment in the microscopic world of molecular bonds other than a reverence for its inspirational aesthetics. She is more of a distinguished alchemist, concocting transformative illusions that are eventually apprehended as flirtatious hoaxes designed to question those perceptual capacities that the habitual gaze takes for granted. The fragile facades Donovan constructs elicit an atmosphere of masquerade, concealing the identity of her chosen material and initiating a choreographed gestalt in the viewer that occurs when the conditional relationship of part to whole ultimately breaks down.

Donovan prefers the phrase “site-responsive” to describe the affiliation of her structures to the spaces they inhabit. While this term makes a convenient allusion to the chameleonic visuals at play in her work, it also suggests a dependence on the architectural particulars and lighting conditions of a given space that environmentally impact the growth of her work in terms of scale, direction, and orientation. Ignoring the notion of the gallery or museum as primarily a contextual space, Donovan inspects a potential exhibition site with an agenda similar to that of a devoted real estate agent, skillfully balancing the needs and desires of her works in accordance with their means and the square footage available. This kind of domestic assessment, relating to “quality of life,” provokes another analogy common to discussions of Donovan’s work. The biomorphic is an undeniable, although not entirely intentional, attribute of her structures. She offers that this characteristic “is more of a phenomenon that I discover than a conscious part of my procedure. . . . My work might appear ‘organic’ or ‘alive’ specifically because my process mimics, in the most elementary sense, basic systems of growth found in nature.” It is as if her isolation of a material rescues it from a prescribed purpose and sets into motion a complex reversion that enables its innate personality to assert itself.

Who knew clear plastic drinking straws had such vaporous and undulating aspirations? Haze (2003) permitted their collective confession when a mega-conference of nearly two million of them was convened by Donovan at Ace Gallery New York last year. Forming craggy peaks reaching as high as thirteen feet, they were stacked in a perpendicular orientation along the length of an entire wall, resulting in a buttressed vertical plane with dense atmospheric qualities from afar given that both light and air permeated the entire structure. In relation to the wall, Haze acted as a thick scrim gone wavily slack as straws pushed flush to the surface created stabilizing recessions for the hills of others projecting further into the room. Gallery-goers unconsciously performed dances of homage to a marvelous visual oscillation that corresponded to each of their parallel movements as pixilated views of the wall appeared and receded. It was a fugitive effect that could also be magnified or minimized according to one’s distance from the facade.

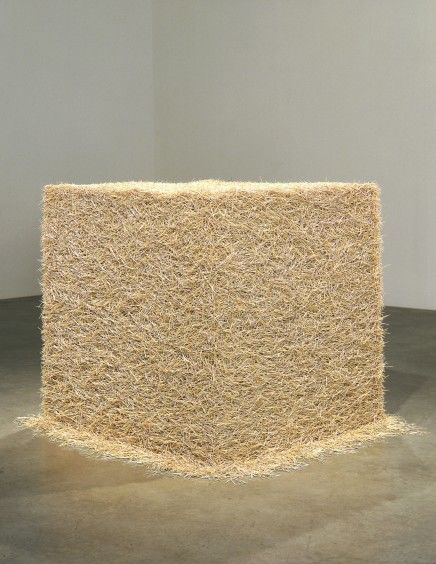

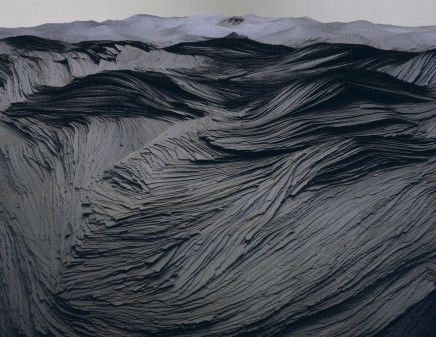

Transparent and translucent materials are a relatively new and particularly effective preoccupation for Donovan in achieving ethereal sublimations, which sharply contrast with the intense gravity of earlier works such as Transplanted (2001). Constructed from ripped and stacked pieces of roofing tar paper, Transplanted appeared as if a congealed square block of rolling gothic terrain erupted from a fissure in the foundation of the gallery. Its surface, formed by sequential layers of ragged paper edges, merged into an astronomical diorama that seemingly mapped a prehistoric or alien topography. In stark contraposition to the terrestrial trappings of Transplanted, Donovan’s untitled work of 2003 was a creature that descended from the celestial realm. A meandering cluster of Styrofoam cups, bonded with adhesive and suspended from a sky-lit ceiling, hovered like a frozen emission that Donovan somehow wafted into the gallery. Each cup adopted the character of a simple lampshade, pressing a warm glow of diffuse natural light into the room. An obvious reference to a billowing cumulus cloud was mandatory but also somehow inadequate as a clichéd response. The hollow volumes of the vessels, encapsulated by walls of extruded molecular puffs, seemed to conjure their own act of levitation, which animated the overall structure with the demeanor of an illusory apparition.

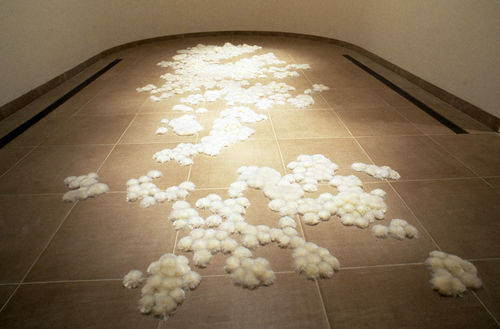

Lure (2004), Donovan’s contribution to the Hammer Projects series, ambiguously situates itself somewhere in the living realm between earth and sky. Segments of monofilament (more commonly known as fishing line), cut to approximately an inch and a half each and numbering in the millions, are divided into neat vertical bundles. When released on the floor, the segments splay concentrically outward, forming spiny interlocking globules when nestled together, which multiply into a sprawling hoard in accordance with Donovan’s repetitive placements. Heaping creates delicate crests that ooze into puddles, suggesting that a viscous liquid infused with preternatural spores dripped from the ceiling and sprouted in the favorable conditions of the gallery. The monofilament’s fiber-optic capabilities allow it to absorb an ephemeral spectrum of pastels gleaned from shifts in light density. As in Donovan’s other works, this evanescent effect entreats an otherworldly association that coalesces with Lure’s hyperfragility to suggest an organism transplanted from a liquid dimension. Its succulent seductions are of the tactile variety that beg for caresses, but it holds out the possibility of a stinging rebuke that enforces a respectful distance.

Finding ways to subvert our relationships with the materials lubricating the metabolic forces of consumer culture is no easy task. Once introduced, these materials are canonized with a resounding sense of intended purpose that seamlessly travels through the symbiotic realms of invention, manufacture, commerce, and lifestyle. The gestalts Donovan activates launch cerebral portals that circumvent these dogmatic intentions, informing our conventional perceptions of everyday visual landscapes by arming us with an optimistic eye toward the fantastic potential of the mundane.

Paul Brewer is an independent curator and writer based in New York.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.

Tara Donovan's residency is made possible by a grant from the Nimoy Foundation.

In-kind support for Lure, 2004 provided by Remington Arms Company, Inc.