Hammer Projects: Santiago Cucullu

- – This is a past exhibition

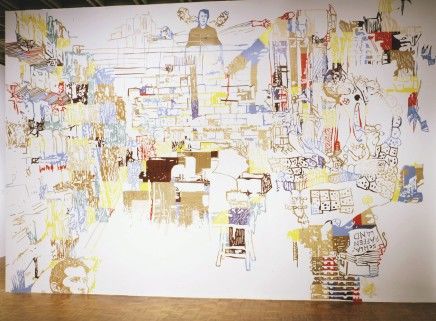

Created from large sheets of contact paper collaged onto the wall, Santiago Cucullu’s pieces juxtapose images of progressive, historical figures and events drawn from references such as the Italian-Argentine radical Severino di Giovanni, the band Led Zeppelin, and the plays of Samuel Beckett alongside those from his personal experience. For his Hammer Project, Cucullu explores imagery from and about the F.L.A. (Libertarian Federation of Argentina), an anarchist library in his hometown of Buenos Aires.

Organized by James Elaine, curator of Hammer Projects.

Biography

Santiago Cucullu was born in 1969 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and currently lives in Milwaukee. He received his M.F.A. from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 1999 and his B.F.A. from the Hartford Art School in Connecticut. In addition he was a resident at the Core Program at the Glassell School of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. Recent solo projects include exhibitions at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; INOVA, Milwaukee; Barbara Davis Gallery, Houston; and Julia Friedman Gallery, Chicago. Group exhibitions include the 2004 Whitney Biennial; How Latitudes Become Forms: Art in a Global Age at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and Fresh: The Altoids Collection at the New Museum for Contemporary Art, New York.

Essay

By Brian Sholis

Milwaukee-based Argentinean artist Santiago Cucullu chooses historically marginalized figures and events (often from his homeland’s anarchist movement) as the subject of his works, which include large wall drawings made of contact paper, watercolors, and sculptures. Cucullu’s references to figures such as anarchist and pamphlet printer Severino di Giovanni, Giovanni’s compatriots Alejandro and Paulino Scarfo, their Spanish forefather Fermin Salvochea, and the historian Osvaldo Bayer inflect a typical chronology of revolutionary fervor and protest, usually traced in straight lines from France, Russia, and Italy to the United States and back to Europe. Like Beyond Geometry, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s current exhibition dedicated to reductive modernist art, which brings South American Concrete Art, Argentine Arte Madí, and Brazilian Neo-Concretism into dialogue with contemporaneous North American and European art movements, Cucullu performs a resuscitation. The artist marries biographical details from these largely forgotten lives with places and people recollected from his own, creating composite visual storyboards that mix references to high and low culture, range across the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, and freely jumble the contemporary with the historical.

Cucullu’s mural-scale drawing for the Hammer Museum is perhaps his most ambitious and freewheeling contact paper work to date. Its source imagery is almost comically disparate: some comes from the archives of the Federación Libertaria de Argentina (FLA), an anarchist library in Buenos Aires; other parts reference a drawing the artist made while in school (and subsequently lost) that depicted a pair of Doc Martens with the imagined name Dusty Springfield Rhoades written across the top; and still other fragments allude to Dusty Rhodes, a real-life reporter from Springfield, Illinois, whose name the artist came across coincidentally while listening to a radio report about a police officer dismissed from her force. Cucullu presents everything as a tangle of images on a nearly flat picture plane, which can lead almost to the point of visual abstraction—making it hard to see the trees for the forest, so to speak—but also calls to mind pre-Renaissance religious paintings, which often set down multiple narratives in a single space on a single canvas. Continuing the analogy, Cucullu’s multiple works rendering scenes from the life of Severino di Giovanni, who died in a shootout with police in Buenos Aires on February 1, 1931, can be viewed as a secular rendering of the Stations of the Cross. Inasmuch as Cucullu’s mostly forgotten events and minor characters, in being rescued from the dustbin of history, are elevated to the point of being inscribed directly onto the walls of our institutions dedicated to preserving culture, we might even link his art to the tradition of history painting, substituting police shootouts for extravagant feasts and grand battles.

In a contemporary reading, a viewer can look at the nonhierarchical relationship among segments of Cucullu’s murals as analogous to the equality of anarchist utopian vision, or as representations of the disarmingly random way in which we come across pockets of information in everyday life. And while not quite random, Cucullu’s artistic process definitely incorporates an element of chance. Drawing on pictures from an archive organized by an idiosyncratic system of narrative association, he rarely knows how the finished artwork will look when he begins affixing the contact paper to the wall. (An act that itself mimics the protestor’s wheat-pasting of propaganda posters around the city.) His material—no different from what you’d find in a hardware store and use to line the kitchen cabinets or a set of shelves—comes in a limited range of colors. He arranges a random and roughly geometric pattern of swatches on the wall before outlining and coloring in the negative space of his image in white; the whitened segments are then excised with an X-acto knife, leaving an elegantly composed multicolored cutout ready to be glued to the gallery wall. This process splits the difference between Arturo Herrera, a New York–based artist whose poster cutouts have graceful curves and random colors derived from found material, and Richard Wright, a Glasgow-based artist who almost exclusively paints abstract patterns directly onto the wall. Cucullu nonetheless maintains an improvisational freedom that Herrera and Wright don’t allow themselves, sometimes capriciously combining more than a dozen individual images to create a single artwork. His compositional choices, often made on-site while installing, add a performative element to an art form that already engages in a sophisticated flirtation with traditions of drawing and painting.

Cucullu’s untitled wall work for the 2004 Whitney Biennial is a recent example. The “back story” for this mural includes references to Schlaraffenland (“Land of the Idle”), an imaginary country of leisure and gluttonous luxury concocted by Germans at the turn of the sixteenth century; Severini and the Scarfos, the Argentinean anarchists; and modernist architecture in Argentina and Japan. Utopia—whether imagined, protested for, or laid out in concrete and glass—is the linchpin linking these images. The connection may not belong entirely to Cucullu, however, as many Germans, some no doubt familiar with the Schlaraffenland ideal—it’s the subject of a 1566 painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, now in the collection of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich—immigrated to Argentina during the first decades of the last century. The pull of utopias, whether entirely fanciful or potentially realizable, has brought people to South America since the first stories of El Dorado, the fabled “City of Gold,” circulated hundreds of years ago (coincidentally within two years of Hans Sachs’s popular satire of Schlaraffenland in Germany). Severini left Italy for Argentina in 1927 to escape the Fascists and start afresh. Cucullu’s artworks integrate this history without becoming didactic or losing their visual appeal, locating it within a matrix that also includes references to the rapper Eazy-E, the 1979 film The Warriors, and countless other cultural touchstones that have their own appeal in our day. It’s a natural human tendency to anthropomorphize abstraction, to look for representations of ourselves in that which doesn’t readily divulge its secrets. Cucullu’s art, made with a sleight-of-hand that turns ordinary materials into spectacular constructions filled to the brim with content waiting to be “unpacked,” consistently rewards this kind of extended looking.

Brian Sholis is a writer based in Brooklyn.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.

Santiago Cucullu's residency is made possible by a grant from the Nimoy Foundation.