Hammer Projects: George Raggett

- – This is a past exhibition

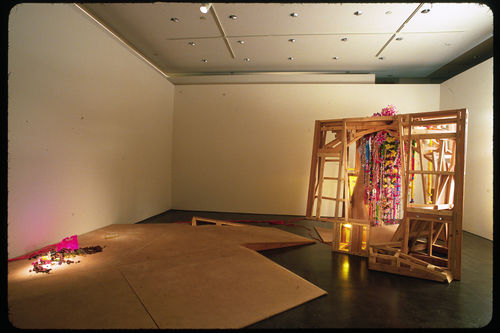

Los Angeles artist George Raggett presents his sculptural installation of an off-kilter gazebo in the Lobby Gallery. Poking fun at false cheer affected by popular, Westernized interpretations of the Chinese art of feng shui, Raggett’s radically asymmetric gazebo calls attention to its own disfunction. This giddy garden getaway cultivates myriad other references—to the history of landscape and park design, the tradition of the English Picturesque and English garden follies, religious festive objects and modernist plinths, for example—all of which visually collide in a dizzying, disorienting architectural enclosure which undermines expectation of the gazebo as a calming space of meditation and retreat.

Co-organized by James Elaine, curator of Hammer Projects, and Claudine Isé, former assistant curator at the Hammer Museum and now associate curator of exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio.

Biography

George Raggett was born in 1972 in Las Vegas, Nevada, and received his B.A. from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1996. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles. He has shown at Acme and at Cirrus Gallery, both in Los Angeles, and at White Columns in New York. Reviews of his work have appeared in Time Out New York and the Santa Barbara News Press. This Hammer Project is Raggett’s first museum exhibition.

Essay

By Claudine Isé

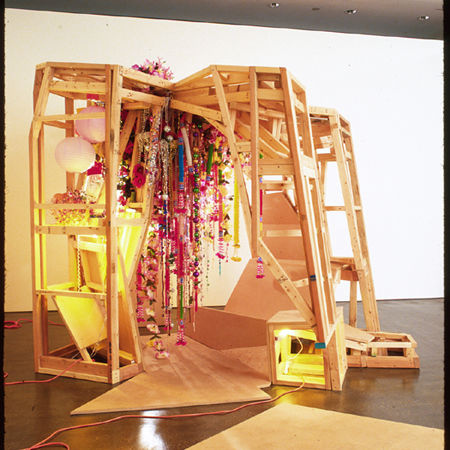

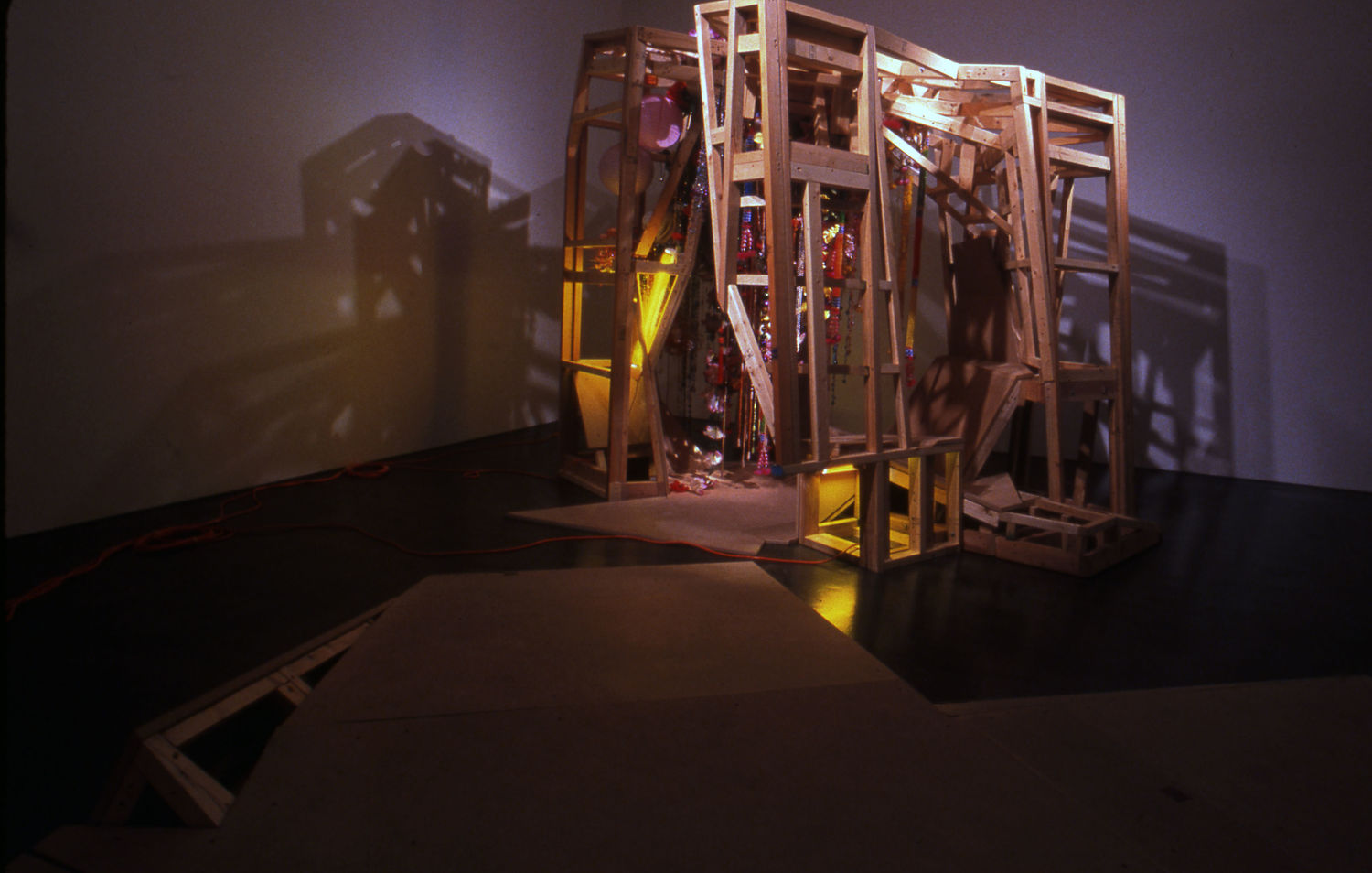

A gazebo is supposed to be a place of tranquil reflection framing a "perfect view," but Gazebo! (2004), George Raggett's off-kilter version of this classic garden idyll, subverts these ideas at every turn. Gazebos are a type of garden "folly," so named for their extravagant and essentially useless nature. Gazebos are places of contemplation, rest, and quiet conversation, often of a romantic nature. Generally they are tucked into slightly out-of-the-way garden locales so that it seems as if one is happening upon them by chance rather than design. For his architectural installation in the Hammer's Lobby Gallery, Raggett draws on the history of garden follies along with that of the English Picturesque style, which is characterized by a pastiche of different architectural idioms—most typically those of Late Medieval cottages and country houses from the Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean periods—brought together in harmonious balance. In contrast, the asymmetry of Raggett's garden folly cum site-specific museum environment calls attention to its own dysfunction. Devoid of either curves or right angles, Gazebo!'s wood-frame exoskeleton is crystalline, even appearing at points to thrust menacingly toward the sitter's body rather than to symbolically embrace and protect it. Projecting outward from one side of this structure is a long plank or bench that bridges the gazebo and the gallery walls while also providing a conversation and lounging area for Raggett's viewers/guests. Carpeting flows out from the gazebo toward the gallery's entrance, providing a literal pathway for viewers that also serves as a material bridge between the interior and exterior of the gallery proper.

Gazebo! was conceived in part with the Lobby Gallery's unique location in mind. The gallery is adjacent to a major thoroughfare of museum traffic, the entryway from the parking structure into the museum lobby, where floor-to-ceiling glass windows provide a view onto the sea of traffic flowing through the intersection of Wilshire and Westwood Boulevards. The placement of the gazebo in a gallery near the museum's main entrance highlights an ongoing way-finding issue with the Lobby Gallery and its environs: museum patrons have a tendency to walk past this room in their haste to "get to the art," never realizing that their first potential encounter with it lies just a few steps away from the parking lot. Other viewers hesitate before entering the gallery, unsure whether access is permitted, where to proceed, or how. In this way an encounter with Raggett's Gazebo! depends almost as much upon the principle of "accidental wanderings" as do real garden gazebos.

Raggett's architecturally inspired sculptures and site-specific environments also make reference to the protoplasmic, organically inspired contours of contemporary architecture and design--forms that often appear to ooze and spread, in complete antithesis to the modernist tropes of cube, stack, and grid. Today architecture and product design speak the language of intimacy, particularly with respect to the human body; contemporary design objects are often pocket- or palm-sized and portable in nature: think iPods, cell phones, and Palm Pilots. In fact, this new breed of designer objects are a lot like pets: companionable, soft to the touch, eager to please.

This "friendliness factor" is seen in many of Raggett's earlier works, such as Nightlight 1, 2, 3 (1996–98), The Pet (1997), and The Climb (1997). Nightlight 1, 2, 3, a glowing, craterlike blob form that plugs into an ordinary light socket and looks like an amoeba or a supermagnified view of a follicle. The Pet lies on the floor like a small cat or dog curled up for a snooze. Its smooth surface and rubbery, rosy hues (shades that bring to mind a dog's lolling tongue) seem to crave human touch. The sculpture simply comprises the letters Y-E-S: a statement of affirmation and permission that seems to sum up much of Raggett's philosophy. The Climb—there are only three steps in all—is a pale, cotton-candy pink. Resting on the floor like stepping stones, a bridge, or yet another sleeping pet, the piece can be easily overlooked. But if a person does take those steps, she will find that each footfall slightly reorients her view of the room, altering her perception of her own body in space. Raggett is well aware that works like The Climb might not be immediately recognized as interactive in nature. The risk of their "failure" is part of the point. But to view his works as traditional "hands-off" sculptures set off from their environment would be to profoundly misunderstand them and, for that matter, to miss out completely on the whimsical perceptual epiphanies that they frequently supply.

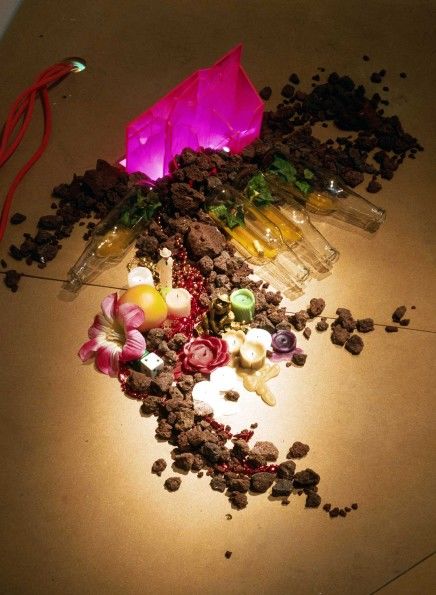

Gazebo!’s goofily utopian premise is that these turbulent times call for a new and radically user-adaptive form of public sanctuary. Dangling from one side of the gazebo are a proliferation of colorful beads and trinkets, culled from various regional ethnic markets, that look like a feng shui device gone haywire. These plastic gewgaws are given an artificially windswept movement through Raggett's addition of a small portable fan aimed directly at them. The traditional Chinese practice of feng shui—the science of placement—is meant to bring harmony to spaces filled with discordant energy. This is achieved by balancing the energy flow, often through the strategic placement and/or rearrangement of objects within the home or business place. An ancient practice, feng shui has been popularized over the past few years into a designer trend emptied of any real cultural or philosophical meaning. Raggett, with his signature blend of irony and sweetly unabashed optimism, gently pokes fun at the colonization of this practice by the language of contemporary interior design while at the same time asserting a very real need to inject a little peace and harmony into a world that feels increasingly insecure.

For Raggett, a sense of balance, an opportunity to engage with one's surroundings in fresh and meaningful ways, is something that one must willfully seek in order to find. An encounter with Gazebo! suggests that making peace with one's environs calls for active, not passive, engagement: a willingness to take a step in the wrong direction, to tweak one's view of the ordinary, in order to transform the everyday world into a twenty-four-hour-a-day adventure.

Claudine Isé, former assistant curator at the Hammer Museum, is now associate curator of exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio.

Hammer Projects are made possible with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Annenberg Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and members of the Hammer Circle.