For Better or For Worse

- – This is a past exhibition

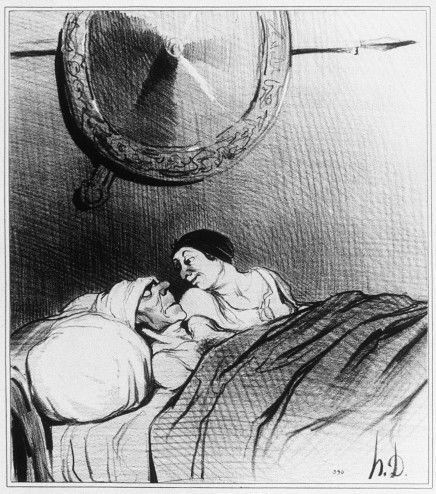

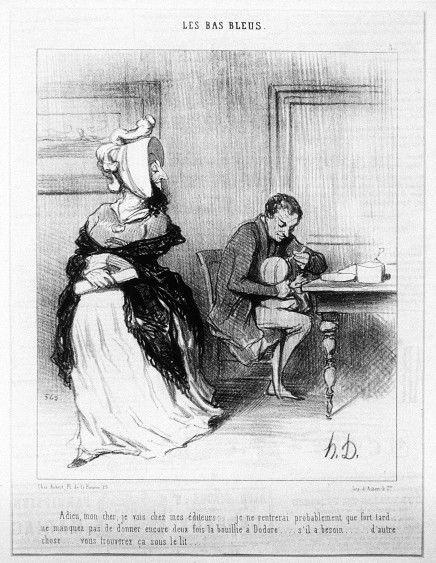

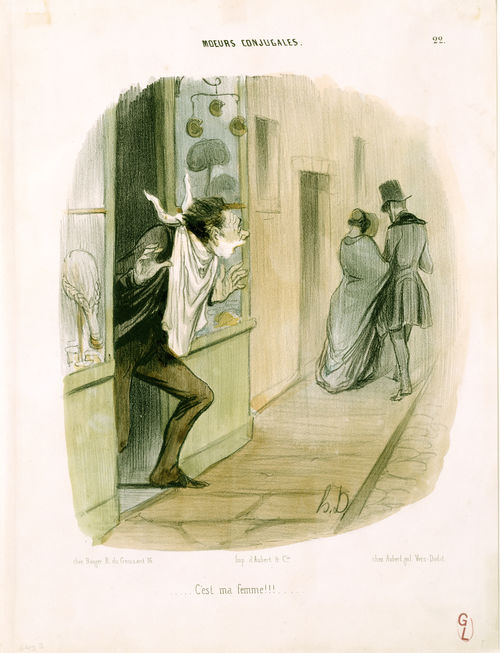

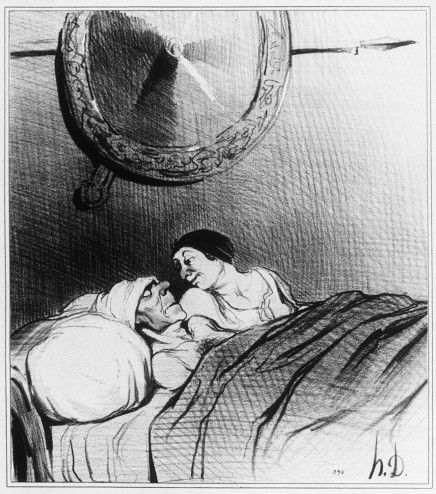

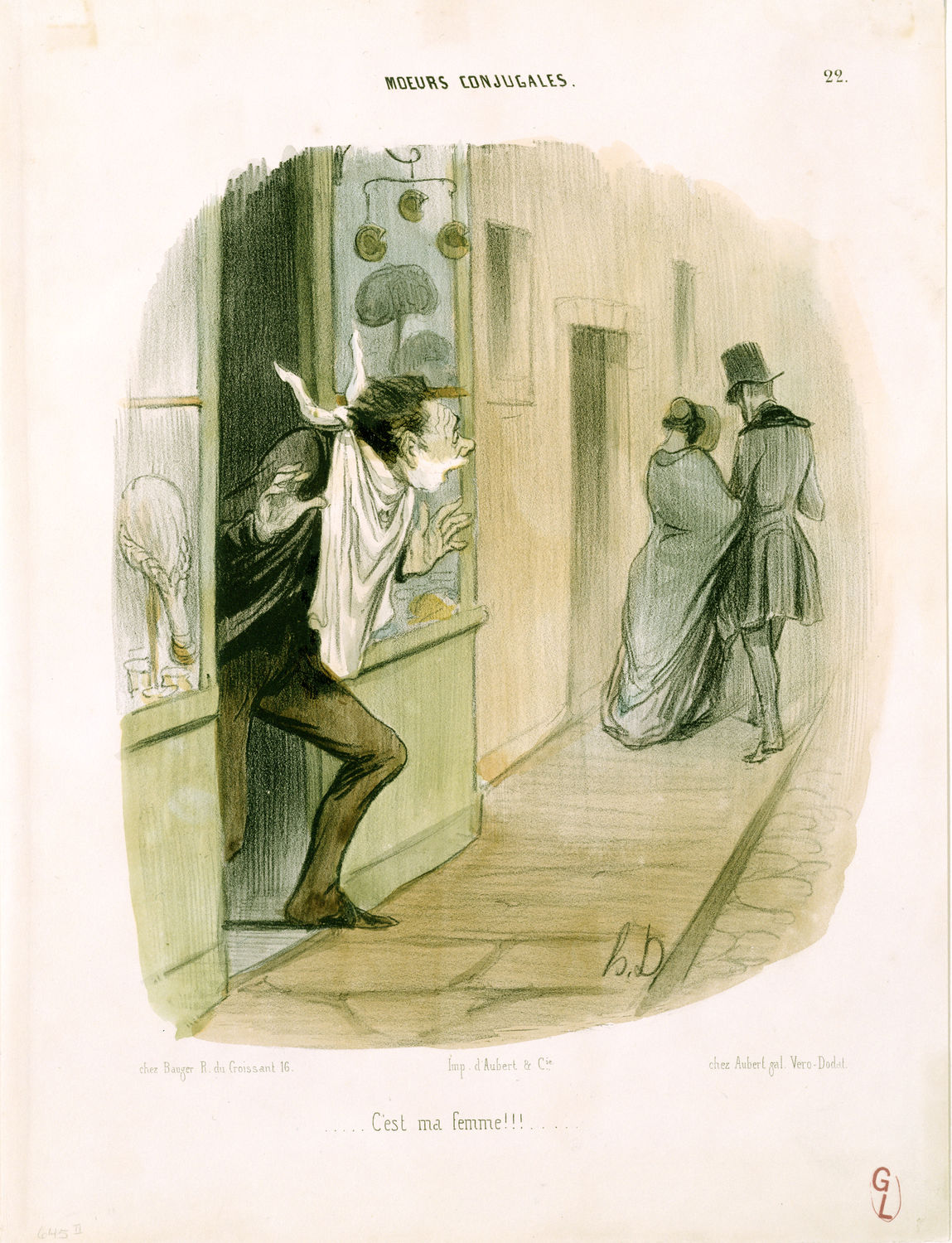

While we might like to think that love, marriage, and relationships were much easier to navigate in the nineteenth century than they are today, Honoré Daumier’s caricatures prove us wrong. Throughout his career, Daumier explored affairs of the heart, highlighting both their joys and challenges. From euphoric scenes of couples courting and falling in love, to couples grappling with parenthood, to unfaithful husbands and wives, to elderly men and women who still have a spark of romance, Daumier’s lighthearted images reveal that human nature certainly has not changed much in over 160 years. This exhibition is drawn from the Armand Hammer Daumier and Contemporaries Collection.

For Better or for Worse: Daumier on Love and Marriage

By Carolyn Peter

Throughout his career Honoré Daumier (1808-79) explored affairs of the heart, highlighting both their joys and challenges. While we might like to think that love, marriage, and relationships were much easier to navigate in the nineteenth century, Daumier’s caricatures prove us wrong.

In the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789, traditional gender roles and the institution of marriage were questioned. The idealistic revolutionaries sought to make things more equal among men and women by legalizing divorce, creating equal inheritance rights for all children, and allowing women more control over their dowries. While not all these radical legal and economic changes were long lasting, they signaled some type of social shift.

With the rise of Napoleon and the introduction of the Napoleonic Code, France reverted to some more patriarchal policies. At the same time, the concept of the nuclear family—husband, wife, and children—was ingrained as a foundation of the French social structure. A bourgeois woman became the primary caretaker of her children. She was expected to maintain the household and to be obedient, passive, and modest about her intellectual abilities. The man’s realm was outside the home; he was expected to support the family financially and to be dominant. Infidelity was seen as a great threat to the sanctity of the nuclear family, particularly if the wife was the cheating party. Neither men nor women had a great deal of recourse in unhappy marriages as divorce was again outlawed from 1816 until 1884. The ramifications and punishment for adulterous women were, however, much harsher than for men. Women could be sent to jail or to a convent.

Some of Daumier’s caricatures show tender aspects of courtship, love, and seasoned relationships. He portrays the euphoria of newfound love, the eventual boredom and routine of marriage, the comic situations of parenthood, and the nostalgia and sweetness of mature love. Other images by Daumier touch upon some of the dicey issues surrounding love and marriage. He depicts adulterous women in compromising situations and the courtroom trials that sometimes follow, children whose paternity is in question, and intellectual women who refuse to fit the mold of housewife and mother. While Daumier’s images highlight the hypocrisies of the institution of marriage, they also take a moral stance, advocating marriage, the nuclear family, and traditional gender roles. This exhibition is drawn from the Armand Hammer Daumier and Contemporaries Collection.

This exhibition is organized by Carolyn Peter, assistant curator, UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts and curator of Daumier exhibitions at the Hammer Museum