Tomoko Takahashi

- – This is a past exhibition

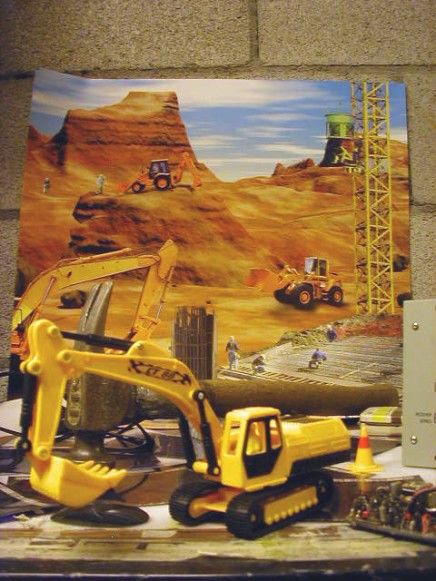

Tomoko Takahashi's chaotic installations imbue ordinary objects with renewed life. Consisting of “found objects” and rubbish that the artist arranges in sprawling installations, Takahashi's displays may at first appear to be random piles of discarded refuse. Upon closer inspection, however, a sense of underlying order is revealed. Resisting clear-cut narrative “readings” Takahashi's installations are associative and abstract in nature, highly schematic yet also deeply intuitive.

Takahashi's installation occupies the unfinished concrete shell of the Hammer Museum theater. Incorporating materials scavenged from the streets of Los Angeles, electronics junkyards, studio prop houses, and other sources of industrial refuse, Takahashi has created a highly idiosyncratic "map" of our city as seen through her eyes. Hammer assistant curator Claudine Isé says, "Tomoko Takahashi's installations pose a challenge to her audience. One of the clichés often used to describe modern and contemporary art is that it 'looks like a pile of junk.' Rauschenberg's early combines, for example, were often dismissed on those terms. Tomoko's works certainly can feel overwhelming in their sheer, sprawling mass. But look closer and you see that she has an incredibly intimate relationship to her surroundings. Her installations also invite certain questions, such as why we give such tremendous value to certain kinds of objects while discarding others without a second thought, how we make distinctions between what is useful and what isn't, and what the consequences of those decisions are."

Organized by Claudine Isé, assistant curator.

Essay

By Claudine Isé

Unholy messes make many people nervous, but Tomoko Takahashi feels right at home in them. A pack rat who thinks big, the Japanese-born, London-based artist is known for making labyrinthine site-specific installations brimming with all manner of rubbish, culled mostly from curbsides, dumpsters, Recycler ads, and garage sales. To enter a Takahashi installation is to step into a topsy-turvy universe where objects seem to have taken on lives of their own. Clocks run on their time, not ours; precariously balanced object clusters seem to defy the laws of gravity, rivers of electrical wire snake their way through mountains of technological detritus, and translucent blue light streams from the unblinking eyes of television screens. To Angelenos in particular, Takahashi’s works may bring to mind the tumultuous aftereffects of a major earthquake, but in fact each of her installations is a painstakingly choreographed arrangement of interconnected, artfully chaotic tableaux. As such, her installations have more in common with stage sets than they do with disaster zones.

Not long after she was invited by the UCLA Hammer Museum to create her first major installation on the West Coast, Takahashi came across the Hammer’s unfinished auditorium, a cavernous concrete shell that will eventually become the museum’s new movie theater. She was immediately drawn to the raw, unfinished nature of the space, which had never been used for an art installation before. In the past she has created installations in art galleries and museums as well as in less traditional environments such as a tennis court (Tennis Court Piece, 2000) and a marketing firm (Company Deal, 1997), both in London, and a project gallery adjacent to Staff International, a New York fashion showroom and distribution company (Staff Stuff, 1998). For each new installation Takahashi gains intimate knowledge of a place by paying extremely close attention to the site’s physical and architectural dimensions as well as to the debris that has been left behind by those who work in or otherwise make use of the space.

Takahashi found the Hammer’s auditorium to be in a provocative state of physical and symbolic flux. A nonoperational movie theater that for now is being used as a catchall storage area, the auditorium isn’t functioning in the manner it is meant to, yet architecturally it exhibits many of the basic structures required for its intended purpose. Keeping this in mind, Takahashi decided to transform it into a kind of dysfunctional set for an unfilmed movie about Los Angeles and its environs, with herself as set designer and art director. Armed with a truck and two knowledgeable assistants, she filled the space of what would eventually become Auditorium Piece (2002) with refuse collected from the streets of L.A. as well as from movie studio prop houses, warehouses, and back lots. Significantly, she thinks of all of the materials she collects as “props,” whether they are acquired from a prop house or picked up off the street. A coffee maker is a “domestic prop,” for example, as is a piano or a mattress. By likening her objects to props, Takahashi foregrounds the fact that their symbolic value depends upon the particular context in which we find them. Once discarded, an object is dislodged from its everyday, time-bound functions and is free to assume new ones in the same manner as a prop, which takes on different symbolic meanings depending upon its function and placement within a scene.

Over the years Takahashi has become an expert “dumpster diver,” but even she was impressed by the sheer quantity of thrown-away material she found deposited onto the curbsides and in the dumpsters of Los Angeles. She was equally amazed by the strange, postapocalyptic beauty of the nearby desert areas, landscapes strewn with abandoned car parts, rusty cans, and old tires that were there for the taking. As Takahashi’s installation progressed, a visitor to the auditorium would note new finds appearing on a daily and even hourly basis. A stack of old doors, a broken window, and a soiled mattress covered in flowered ticking showed up early on. Subsequent days brought several washing machines, a microwave oven, a rickety bedside table with peeling white paint, a number of plastic toy cars and trucks, and the entire cockpit of an airplane, stripped of its wings and metal exoskeleton like some prehistoric creature that had mysteriously fallen to earth. A hot tub, a piano, a giant sign spelling out “Wednesday Night” in lights, and large quantities of dead plant rubbish and brush also found their way into the space. Takahashi dusted sections of the installation with a fine layer of synthetic snow, a gesture that encapsulates her sense of wonder and bemusement at the Los Angeles landscape’s peculiar combination of the natural and the artificial. She has also provided viewers with opera glasses so that they can zoom in on selected details of the piece, thus adding a key interactive element to her ambitiously scaled production.

Takahashi has often noted that the anarchic appearance of her works is in truth a “designed disorder.” For each installation she devises a set of rules or categories that structure the overall composition; within those rules, she has complete freedom to do what she wishes. In the resulting installations, we may find temporary freedom from the rule of law as well as from language, history, and hidebound notions of who we are or should be. Embodying the true spirit of the anarchic impulse, Takahashi’s installations are like fleeting acts of war: at once overwhelming and short-lived territorial occupations that will fundamentally alter the way we think about and remember a place forever afterward.

Trained as a painter, Takahashi takes the entire expanse of a space into account while activating certain areas of her mammoth, three-dimensional collages through use of light, color, movement, and sound. The musical and rhythmic aspects of her object arrangements serve a similar function. Focal points–often volumetric areas of dense accumulation–function as dramatic crescendos. Smaller groupings, sometimes bounded by lines of tape or marker, provide staccato accents, with diagrammatic projectile elements bridging these different “movements.” There is usually an acoustic component to Takahashi’s works, sometimes provided by prerecorded sounds and other times simply by the clicks, clacks, whirs, and hums of the various pieces of technology she brings to the site, which are in turn complemented by random noises made by the air conditioners, heaters, pipes, and other electrical units that already occupy a given space.

Takahashi’s use of refuse as raw material reminds us of what should be obvious but often isn’t: a thing doesn't simply disappear just because we’ve chosen to throw it away. Importantly, however, her installations are not meant to provide sociopolitical commentary on conspicuous consumption or the benefits of recycling. Instead, by freeing objects from their prescribed social and symbolic “roles” and employing them in the creation of astonishing new environments, she reminds us that the anarchic impulse can be a powerful and productive force of creative transformation.

This exhibition has been made possible through the generous support of The Japan Foundation Los Angeles Office, the British Consulate-General, Los Angeles, and the British Council.

In-kind support has been generously provided by the Doubletree Hotel, Los Angeles-Westwood.