Mirror Image

- – This is a past exhibition

This exhibition offers selected artists’ experiments with the practice of self-portraiture. Featuring pieces spanning from 1797 to 2002, the images toy with the viewer, forcing us to question not only how these pictures truly reflect the artists on display, but how honest our own mirror images are in representing ourselves. Mark Bradford, Patty Chang, James Ensor, General Idea, Francisco de Goya, Richard Hawkins, Larry Johnson, Martin Kippenberger, Oskar Kokoschka, Nikki S. Lee, Christian Marclay, Robert Rauschenberg, and Gillian Wearing are all featured in the exhibition.

Essay

By Russell Ferguson

Empty eyeballs knew

That knowledge increases unreality, that

Mirror on mirror mirrored is all the show.

—W.B. Yeats, "The Statues" (1938)1

The mirror offers a double-edged gift: it gives whoever looks into it both a truthful reflection and a false image, reverser from the face that everyone sees. The mirror imposes a separation between ourselves and our image. This exhibition looks specifically at the gap between likeness and authenticity. Self-image here is accepted as something inherently mutable, available to artists not just as simple reflection. A portrait of someone else can be a kind of capture of their identity through their appearance, but when artists depict themselves, the results can often be a kind of liberation from fixed identity. In 1978 James Ensor made a drawing of himself as a fisherman. We see what the artist looked like, yet we also see his body in use as a kind of raw material that can be mythologized, commodified, and even fictionalized.

The earliest work in this exhibition is an etching by Francisco de Goya. On one level this work is a simple profile taken from a mirror. Accompanied by its inscription, however, Goya's face does double duty, serving as the introduction to his prints, Los Caprichos. While remaining a record of his actual appearance, the image also becomes an advertisement and an assertion of authorship. The artist's appearance becomes the touchstone for a series of other works, authenticated by the self-portrait that announces them. The tradition of the self-portrait as advertisement has continued strongly to the present day. In Oskar Kokoschka's 1923 poster for an exhibition, the artist's image is again used to announce a whole group of other works. Kokoschka depicts himself simultaneously full-faced and in profile, an evocative double image that traces his gaze moving away from and back to the mirror.

In more recent times, Martin Kippenberger frequently used his own image in posters in which he simultaneously promoted and mocked himself, as his self-presentation oscillated wildly between genius and buffoon. The poster shown here, from 1978, is on one level promotional material, like most posters, yet the artists image is surrounded by derogatory characterizations: "informer, peeping Tom, pimp," and so on. The result is a typical example of Kippenberger's capacity to mythologize himself yet debunk the process even as it is underway.

Robert Rauschenberg's monumental triple print Autobiography (1968) does not shy away from the mythic. While the central panel's spiral of text gives a factual account of Rauschenberg's life and career, the powerful images that surround it, most notably the iconic photograph of the artist on roller skates with a huge parachute flaring out behind him, suggest a persona bigger than the merely personal. Rauschenberg's emphasis on the performative elemant of his own identity implies a broader performative element to identity in general.

Christian Marclay's series of posters from 1994, False Advertising, takes self-presentation in a more overtly fictional direction. Posing as different types of musician—classical, rock, folk, jazz and chansonnier—Marclay presents himself in posters for apparently real concerts in Geneva. These false advertisements were actually widely posted there, causing some genuine confusion. Marclay is in fact a musician as well as an artist, but not one who works in any of the genres shown on the posters. Instead he melds his own (real) image with the stereotypical traits associated with a given genre, not just by adopting particular forms of appearance but also through sophisticated parody of the appropriate styles of poster design.

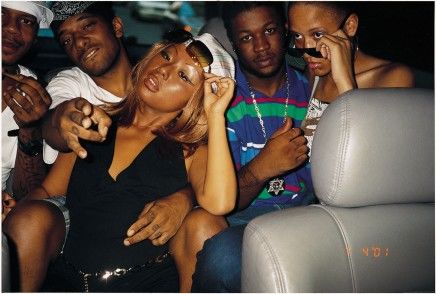

Nikki S. Lee also adopts different personae in the course of her work, but she takes the performative element even further. For the duration of a particular project, she fully inhabits her role as a member of a particular group in society. In this exhibition she appears as a yuppie and as a player in the world of hip-hop. In each of the thirteen projects she has undertaken, Lee has demonstrated an almost uncanny ability to absorb the visual and behavioral codes that grant entry to a particular milieu. The photographs that serve as the projects' record are snapshots taken by whomever Lee hands her camera to. While they are all on one level portraits of the artist, they also suggest how disturbingly easy it might be to change identities. For Lee, her various roles are not disguisers; they are potentially ongoing possibilities.

If Lee's photographs suggest a certain confident ability to switch from one persona to another, the work of Patty Chang raises a more unsettling image of the artist as inhabitant of a body that is out of control. In Candies (XM) (1998), Chang's mouth is clamped open, and is full of candy. The evident result is that she is drooling onto her very proper suit. In her untitled video of 2001, there is clearly something (or things) moving around under her shirt, to her visible distress. Chang's apparent loss of control over her body in these pieces (both derived from live performances) is undercut by the viewer's realization that the work itself could have been made only by an artist who was in fact exercising a high degree of control, over herself and her work.

Gillian Wearing's Self-Portrait (2000) also suggests a struggle of control over the artist's body. The mask that Wearing wears over her own face resembles her, but its rigidity denies the possibility of any visible emotion. The effect, however, is to make her real eyes all the more intensely vulnerable and human behind the frozen mask. Wearing's work explicitly suggests the possibility of a split personality. The eyes looking out from behind the mask can be read as a kind of metaphor for a broader contest between an authenticity that is still presumed to exist under the surface and the image that is presented to the public.

Mark Bradford's double image of himself, Earth, Wind, and Fire (2002), raises some of the same questions. We presume that one of his two images is reversed, but we don't know which. Is one more authentic than the other? Bradford, shown with a pair of bellows, positions himself specifically in relationship to icons of black history, not just the 1970s funk group referred to in the title, but, more tellingly, to James Baldwin and "the fire next time." He goes beyond even these iconic references, however, to link himself to elemental forces of nature. The mythic here is directly stated, albeit with a sense of humor.

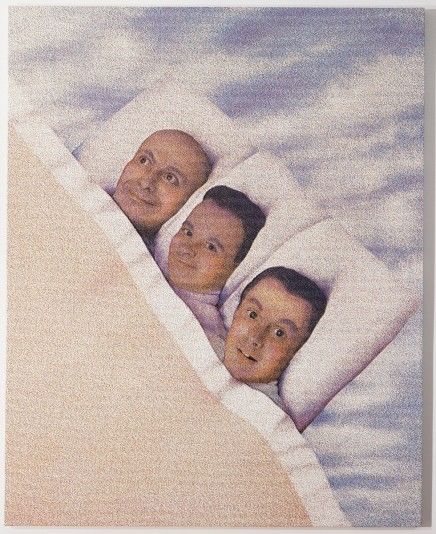

General Idea had its own take on the idea of divided identity, since the group was made up of three artists. Rather than demonstrating the slightest angst over any potential conflicts, they present themselves instead, in Baby Makes 3 (1984/89), as an idyllically happy family, tucked up in bed like characters in an illustration for a fairy tale. Only after a while does one wonder which of the three is actually the baby. All of them? Perhaps what we are seeing here is the opposite of the split personality.

In some cases, artists can make a kind of self-portrait without appearing in their work at all. Larry Johnson very simply makes use of two dates--his real date of birth and an earlier (wrong) date printed in an exhibition catalog--to indicate The Difference between Forty-five and Thirty-six. The melancholy of this piece lies in the gap, and the inexorable movement through it. As Alighiero Boetti said in 1972: "If you write, say, '1970' on a wall, it seems like nothing, absolutely nothing, but in years time. . . Every day that passes makes the date more beautiful."2 Similarly, Richard Hawkins's untitled collage from 1996 traces an autobiography of regret, absence, dread and longing through an abbreviated timeline that extends to 2000: the future when the piece was made yet now already in the past. The body moves on, and changes, but here, at least, it leaves a trail behind it.

Notes:

1. Yeats, "The Statues," in Selected Poetry, ed. A Norman Jaffares (London: Pan, 1974), 195.

2. Boetti, in an interview with Mirella Bandini, in Zero to Infinity: Arte Povera, 1962-1972 (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center; London: Tate Modern, 2001), 188.

Russell Ferguson is chief curator and deputy director for exhibitions and programs at the UCLA Hammer Museum.