Hammer Projects: Simon Starling

- – This is a past exhibition

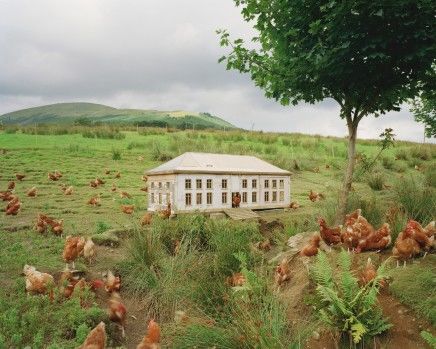

References to music, architecture, social history, and philosophy abound in the work of British artist Simon Starling. Taking the utopian ideal of Modernism as his point of reference, Starling will present Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA (House for a Songbird), 2002 - complete with birds. In the installation in the Hammer's Lobby Gallery, two scale models by Austrian architect Simon Schmiderer of a Puerto Rican housing project dating from the 1960s double as birdcages. They sit atop tree trunks that stretch up from the floor below. Art critic Massimilano Gioni notes that "by replicating the elaborate pattern of steel gates and fences, and by trapping a couple of songbirds in one of his miniaturized houses, Starling evokes the contradictions that disarm and immobilize any version of utopian thought when faced with the unpredictable chaos of life."

Hammer Projects are curated by James Elaine.

Biography

Simon Starling was born in Epsom, Surrey, England, in 1967. He studied at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham, and Glasgow School of Art and currently lives and works in Glasgow. Recently he has had exhibitions at Casey Kaplan 10-6, New York (2002); Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee, Scotland (2002); Vienna Secession (2001); and Magasin, Grenoble, France (2000).

Essay

By Massimiliano Gioni

Two crooked branches of tropical wood sprout from the floor of the gallery like some sort of exotic plant mysteriously insinuating itself into the hard geometry of the white cube. As our gaze follows the gentle curves of the branches upward, we encounter another curious apparition: two miniaturized buildings are pressed up against the gallery ceiling. The miniature models have been flipped upside down; their roofs delicately balance on the tips of the branches like fragile tree houses. In spite of their diminutive scale and awkward positioning, the houses still manage to preserve the lean austerity so typical of modernist architecture, with its glacial proportions and severe elegance: sharp angles, clear-cut windows, and airy patios, the division between interior and exterior completely blurred. But—again—the purity of these solutions is corroded by another anomaly: the once open structure has been enclosed by steel gates and screens. The buildings have been transformed from open-air abodes into claustrophobic cages. And, trapped within one of the house’s walls, a couple of colorful songbirds have found their nest.

Like the houses in Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA (House for a Songbird), Starling’s work grows on shaky ground, envisioning a space crossed by different tensions and incongruities. Out of these contrasts, however, a trembling equilibrium always emerges—a moment of suspension that solves and yet exposes a tortuous process of research. Starling’s world, in fact, is perennially in motion: within its fluid borders objects get transformed, values exchanged, contexts overlapped. Whether working on a photograph, a sculpture, or an installation, he never seems content with creating a mere product or image. He aspires instead to use art as a catalyst for a variety of meanings. Starling’s work, then, becomes both the point of departure and the terminus of an endless journey through the spirals of memory and the windings of geography.

The coordinates of Starling’s imaginary expeditions are traced by the titles and notes that accompany his exhibitions: these instructions—or recipes, as the artist calls them—outline a maze of multiple narratives, which often gravitate around a series of historical allusions. In Starling’s projects, in fact, each detail results from careful encyclopedic investigations, while illustrious antecedents are found in order to justify every decision. No matter how absurd or arduous, Starling’s plans are always carried out with the manic concentration one expects to find in the work of a self-taught, obsessed amateur. But the final output is more similar to the findings of an archaeologist who has been studying the metamorphosis of life and culture through the lens of art history.

In Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA, for example, the image of the two houses pressed against the ceiling derives from the combination of two creative methods, one developed by the composer Arnold Schönberg and the other by the architect Simon Schmiderer. Both Austrian expatriates and crucial figures in the tradition of modern art and culture, Schönberg and Schmiderer shared an understanding of, respectively, music and architecture as disciplines founded on rigid, almost scientific systems of modular logic, which were also meant to open up new spaces of creative freedom. In Schönberg’s practice this approach resulted in the invention of a twelve-tone compositional system, according to which, in each musical composition, a single twelve-note sequence could be played in different permutations and forms—original, inverted, retrograde, or inverted retrograde. Schmiderer developed a construction method based on preformed concrete modules: this system revealed its potential in a residential area built in the 1960s on the island of Puerto Rico, where he adapted the teachings of modernist architecture to the exigencies of local culture.

The houses in Starling’s Inverted Retrograde Theme, USA are modeled after Schmiderer’s original plans, but they have been forced into Schönberg’s compositional system: each building has become the mirrored or retrograde image of the other, and both houses have been inverted, hanging upside down from the ceiling. Tuning Schmiderer’s architecture to Schönberg’s music, Starling has created a visual and visionary conundrum, which could be interpreted as a twisted monument to the tradition of modernism. Unlike his predecessors, however, Starling no longer believes in the algid perfection of rationalism. On the contrary, he is more interested in the dramatic transformations that time and use impose on any rigid structure, either aesthetic or ideological. As an anthropologist of dysfunction, then, he also aims to document the subtle variations and the smallest interventions that have radically modified Schmiderer’s original design throughout the years. In the 1970s and 1980s, in fact, Schmiderer’s houses proved totally unsuited for protecting their inhabitants from a drastic increase in local crime. Attempting to defend themselves, the owners of the houses spontaneously began erecting fences and barriers, turning themselves into voluntary prisoners of architecture. Schmiderer’s utopian dream of harmony and perfection had crashed against the insurgence of pure and unplanned disorder.

By replicating the elaborate pattern of steel gates and fences, and by trapping a couple of songbirds in one of his miniaturized houses, Starling evokes the contradictions that disarm and immobilize any version of utopian thought when faced with the unpredictable chaos of life. Subverting the presumed infallibility of Schmiderer’s and Schönberg’s creative methods, Starling lets his work resonate with a cacophony of imperfections and unpredictable developments. That’s why a strange sense of loss also seems to emanate from his work; at the very moment he appropriates the instruments and weapons of utopia, he also points out their limitations and inadequacies. But, then again, like many artists of his own generation, Simon Starling doesn’t seem too preoccupied with finding a perfect solution. He’s more interested in drawing attention to problems and generating doubts. In other words, the final result of his efforts is important, but the trajectory of his journey is more crucial. By literally and metaphorically collapsing different structures and stories on top of one another, Starling’s work superimposes languages and traditions while bringing together different fragments of knowledge.

Overlapping geographies and zigzagging between remote histories, Starling acts as an untiring explorer of hidden routes and secret connections; his sentimental journey unveils a catalogue of elective affinities. And, as it reinjects life into the realm of abstraction, his restless mobility turns into an antidote against the specter of an empty and useless perfection.

Massimiliano Gioni is an art critic and curator. He lives and works in New York and Milan.

Hammer Projects are made possible, in part, with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support has been provided by the Los Angeles County Art Commission.