Hammer Projects: Amy Adler

- – This is a past exhibition

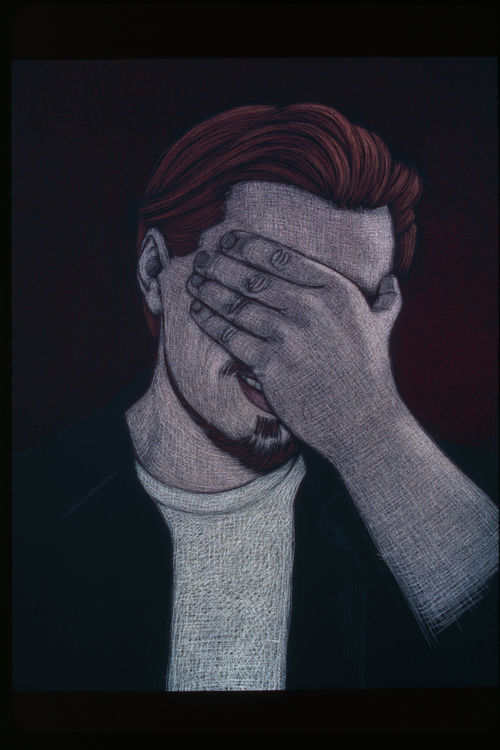

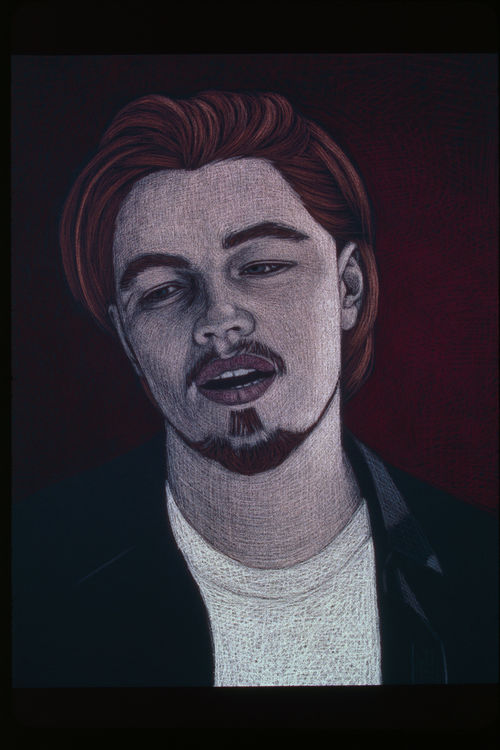

Amy Adler has long been fascinated with public figures-especially movie stars and musicians whose mechanically-reproduced images circulate endlessly throughout our culture and yet whose private identities remain inaccessible to the public. In early 2001, Adler photographed the actor Leonardo DiCaprio at her home in London. Her brief session with DiCaprio proved to be the very antithesis of a celebrity publicity shoot: intimate, casual, and spontaneous. Adler made drawings of the DiCaprio photographs and then photographed the drawings. The drawings and the original negatives were then destroyed, resulting in six singular images that are the only evidence of Adler's encounter with this elusive celebrity.

Organized by Claudine Isé, assistant curator at the UCLA Hammer Museum.

Biography

Amy Adler was born in New York City in 1966. She recently returned to Los Angeles, where she currently lives and works, after a two-year residency at Delfina Studio Trust in London. She studied at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin and received her B.F.A. from Cooper Union and her M.F.A. from the University of California, Los Angeles. She has had solo exhibitions at the Photographer's Gallery in London, Taka Ishii Gallery in Tokyo, No Limits Events in Milan, and Casey Kaplan 10-6 in New York. Adler's work was selected for the Kwangju Biennale in Korea in 2000 and was recently included in The Americans at the Barbican Gallery in London and Form Follows Fiction at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, Italy.

Essay

In 2001, while living in London, Amy Adler arranged a private photo shoot with the actor Leonardo DiCaprio. The shoot took more than a year to schedule, and the actual date and time were not finalized until a day before it took place. Adler recalls that when DiCaprio finally entered her flat, she had the peculiar sensation that reality had momentarily warped: "I wasn't sure whether I had just stepped into his landscape, or he had stepped into mine."1 Adler shot one roll of film, as DiCaprio stood casually, in the light of her bedroom window, and the two talked.

Adler has long been interested in the psychological construction and cultural meditation of identity through mass media images. She frequently chooses to portray actors and musicians, because it is often through images of these idealized figures that we derive a sense of our own identities. Images of celebrities reflect our desires back at us; we define ourselves through and against the qualities with which we imbue them. Although Adler had previously utilized magazine images of recognizable actors from magazines, CD covers, and film stills in her work, her photo shoot with DiCaprio marked the first time that her portrayal of a famous actor was based on a "live," in-person encounter.

All of Adler's projects are executed in several stages, each a generation away from the previous one. Typically she begins with a photograph and makes a series of drawings based on that photograph. When the drawing is complete, she photographs it and then destroys the drawing. In the case of the DiCaprio project, she destroyed the prints and negatives from the photo shoot as well as the drawings, acts that were emotionally difficult yet critical to the piece. In destroying the physical proof of the meeting, along with the labor-intensive drawings she made in response to it, Adler ensured that the photographed drawings of DiCaprio (a total of six unique images) would be the only tangible result of their encounter.

Adler likens her individual projects to short films or film clips, and she thinks of her subjects (which often include herself) as "characters" in these films. When installed, the piece resembles a blown-up film sequence consisting solely of jump cuts. In Adler's work the interstitial space between frames is as important as what the individual frames contain. This leads to a certain kind of paradox that is replayed time and again in her various projects. In both film and animation, the moment in which the individual frame or cell is set in motion and "comes to life" is also the moment in which it seems to disappear. Similarly, Adler has said that when her drawings become "animate," or like characters, she knows that they are finished, so that the moment of the drawing's completion also signals its imminent distruction. The point at which Adler's characters appear most "alive" is also that which indicates their impending disappearance, their death. The photographed drawing thus contains the "ghost" of its former incarnations; one could say that the photograph is inhabited - even possessed - by the drawing, along with the photographic image that preceded both.

DiCaprio's elusive persona makes him an ideal subject for Adler. Indeed, she has described him as a "perfect vehicle," making reference to Allan McCollum's Perfect Vehicles - painted vases of varying sizes cast in solid concrete, plaster, or Hydrostone - which McCollum developed in a number of forms beginning in the late 1970s (Adler was once McCollum's studio assistant). The Perfect Vehicles become pure signs, aesthetic objects whose sole purpose is to be contemplated from a distance. What is therefore crucial to Adler's project is the fact that she stood face to face with DiCaprio, a young man who had formerly existed only as an abstract "type" rather than a flesh-and-blood human being.

In popular culture the remoteness of the celebrity's physical presence is partly compensated for by the proliferation of photographic images that function as surrogates, temporarily "filling in" for the star's absent body. Adler's photographs reflect the mechanics of mass-media images "backward," as if in a mirror, so that precisely the opposite result is achieved. Her drawings of DiCaprio call attention to the absence of the original photographs on which they are based - images that would inevitably deliver a far more precise likeness of the actor than Adler's drawings can. In turn, the photographed drawings point to the disappearance of the actual drawings. The resulting hall of mirrors only widens those gaps that photography tries to fill. DiCaprio's presence before Adler emphasized the performative nature of her project (she was, after all, standing in the room with him) and, at the same time, signaled the collapse of the vast distance between the artist and her subject, whom she could previously look at only through films and photographs. Adler recalls feeling during those moments as if a screen that had withheld this particular body from her view had suddenly vanished.

Adler's project not only documents her meeting with DiCaprio and its subsequent recession into memory; it actually restages their encounter through its own implicit narrative of attainment and loss. The title, Amy Adler Photographs Leonardo DiCaprio, is inscribed with a number of ironies. It points to the "liveness" of her subject and to the fact that the photographs of DiCaprio were taken by Adler herself. It also suggests consciousness on the part of photographer and subject that they are each performing in a scripted encounter. The title's declarative, subject-verb-object grammatical structure has the clipped immediacy of a newspaper headline and seems to announce an event taking place in the present. Yet what the work delivers is not something "live," but rather a portrayal of something that took place in the past. The "live" exchange between Adler and DiCaprio was recorded photographically and then recorded again by the drawings, which were then rerecorded by the photographed drawings, each successive recording a kind of entombment that seals the live body, the palpable, breathing moment, further away from view.

The fastidious control that Adler exerts over every stage of this process, up to and including the final act of destroying the drawings, succeeds in making celebrity (which is itself a function of mass-media culture) and photography "behave" in highly uncharacteristic ways. Photography's viruslike ability to multiply and proliferate is arrested by Adler's multiple eradications. By replacing her one-of-a-kind snapshots of DiCaprio with surrogate drawings that took months to complete, and by photographing and then sacrificing these drawings, she bestows upon the final six photographs a singularity that is also a peculiar form of absolution. The exchange is certainly bittersweet, but for Adler it is necessary all the same.

Notes:

1. All statements attributed to Amy Adler are from the author's conversations with the artist, December 6, 2001, and January 4, 2002.

Hammer Projects are made possible, in part, with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.