Hammer Projects: Aaron Noble

- – This is a past exhibition

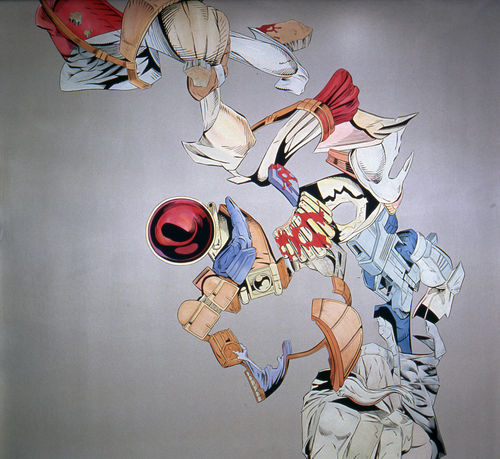

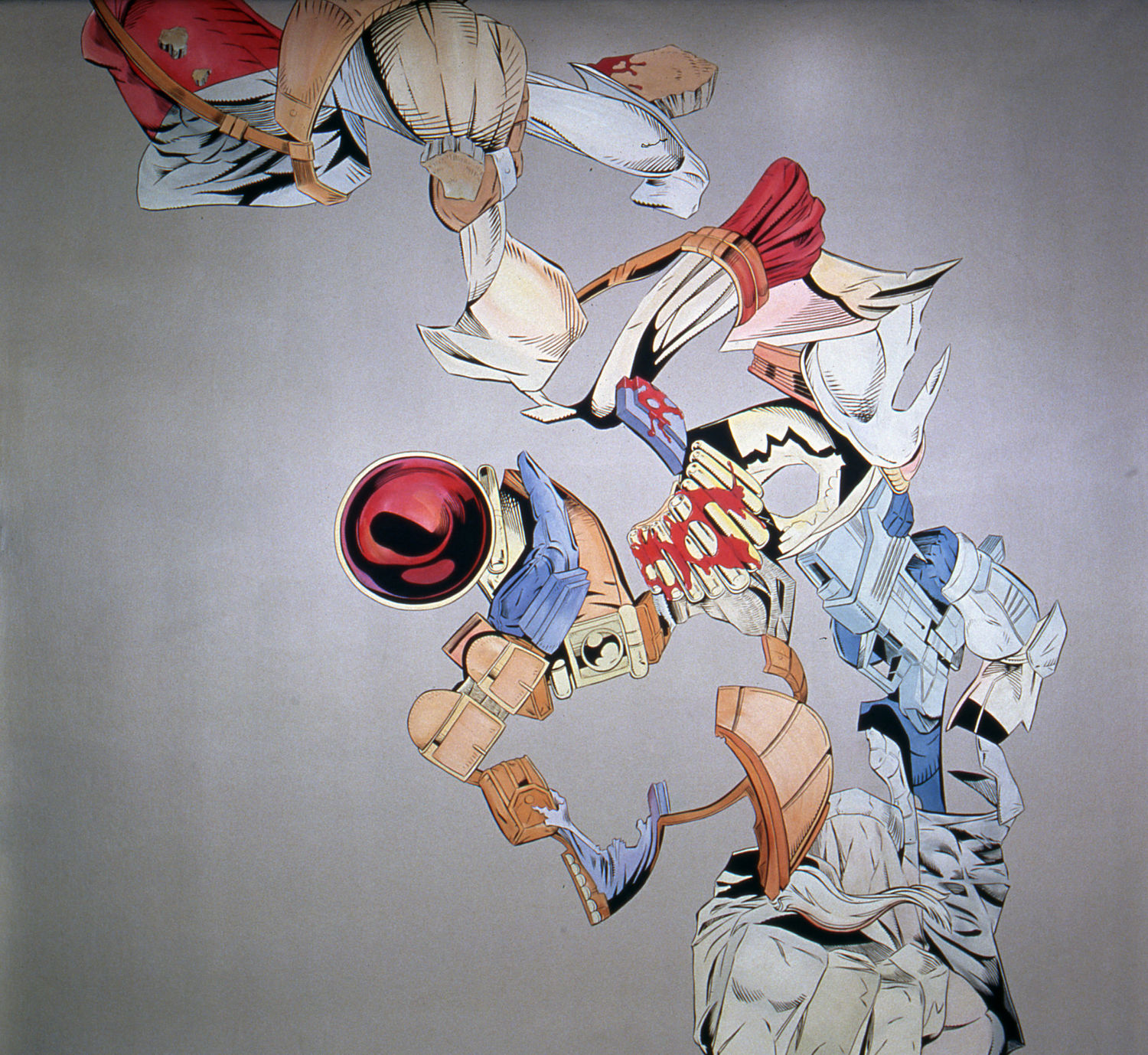

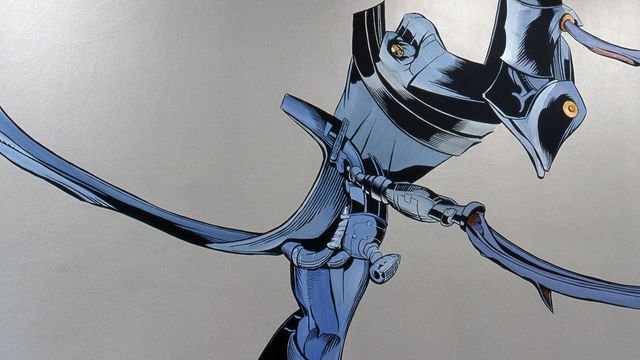

Inspired by comic book imagery, Aaron Noble's paintings incorporate superhero body parts morphed, stretched, and free floating in a "negative space" landscape. He is known in San Francisco for his earlier WPA-styled outdoor murals depicting the city's labor history. Now his interests involve contemporary popular street culture, Western comic art, Japanese anime and manga, video games, and technology. Noble created a series of large-scale paintings for the Museum's lobby walls.

Hammer Projects are curated by James Elaine.

Biography

Aaron Noble was born in 1961 and recently moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles. He is the cofounder of the Clarion Alley Mural Project in San Francisco, where he was director from 1996 until 2001. Last year he created murals on a police guard post in Taiwan, on a private residence in Los Angeles, and, in collaboration with Andrew Schoultz, on an exterior wall on Sixteenth Street near Third Street in San Francisco. Other mural and wall-painting projects include the Theatre Rhinoceros Lobby; Superhero Warehouse on the exterior of 47 Clarion Alley, in collaboration with Rigo 00; and the Labor Temple lobby, San Francisco. This Hammer Project is Noble's first museum exhibition.

Essay

By Scott MacLeod

The superheroic exaggerates the normal proportions of humanity [and] is the expression of both the fears and unfulfilled aspirations of the adolescent. . . . The superhero-like the adolescent-is one apart, someone from somewhere else, someone who does not quite belong-but someone nonetheless needed by society when monsters and demons stir.1

In his 1989 performance Confession, Aaron Noble crawled laboriously atop a table, abjectly confessing his own weakness and perfidy. Wiry, naked muscles stretched taut by the huge guitar amp roped onto his back, face distended by the microphone jammed into his mouth, he called himself an emotional villain, but his body's visible suffering more directly conveyed a mitigating humanity and, ironically, courage.

Villains have always intrigued because of their emotional complexities; in the 1960s Marvel Comics revolutionized its genre by presenting equally alienated, angst-ridden heroes and heroines struggling against limits of human endurance and faith to gain conditional victories over internal and external demons.

Born in 1961 and raised in a counterculture shaped by the murder of heroes (Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X) and the ascent of demons (Nixon, Manson, Kissinger), Noble was influenced by the conflicted ironies and agonies of Kafka, Iggy Pop, and Marvel's superheroes even as he became more politically active and community oriented. He cofounded the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP) in 1992 to support community mural activities in a San Francisco Mission neighborhood coming under psychic and physical pressure from gentrification. In 1994 he painted his first superhero on the exterior wall of his home on Clarion Alley, completing an entire facade of Marvel characters, Superhero Warehouse, in collaboration with CAMP cofounder Rigo 00 in 2000. Even in WPA-style independent murals with overt political content, such as the relatively realistic Redstone Labor Temple and Theatre Rhinoceros murals, Noble's human figures are oddly twisted and stretched, their subtle, unsettling torsion expressing the tension of political conflict or eroticism.

As a muralist, Noble was working in the same physical and social environment as graffiti artists. Both murals and graffiti operate in a public arena, competing with advertising, architecture, the velocity of traffic, and the transient quality of their audiences' gaze. As Noble absorbed the techniques and attitudes of graffiti artists whose style was looser and less formal, he began to think about developing work that could compete with graffiti's frameless spontaneity. Graffiti tends toward minimalist intensity in that the entire work is reduced to its creator's signature, to the speed of line-as-gesture, as opposed to the mural's concern with representation and narrative.

The public arena, the large scale, the permission to paint something aggressively flashy, baroque, and hard to interpret-all come from graffiti.2

In the mid-1990s Noble noticed that superhero comics had become so baroquely detailed that narrative elements were obscured by complex “illustrational” line work. Young artists were distorting traditional tropes of inking, shading, and anatomy, arriving at a density that nearly obliterated distinctions between one figure and another, and between figures and backgrounds.

In 2000 an invitation to make work for Ajax Gallery's Bay Area Disfigurative show inspired Noble to fuse comics' new density with graffiti's speed and scale. Beginning from an intimate, intuitive collage process, he created Slave, a portable mural of dense, abstracted lines of solid super muscle. Soon after, he began working with Andrew Schoultz, a young graffiti artist who had recently painted an impressive mural on Clarion Alley. After an initial project was destroyed before it could be finished, they completed China Basin Mural, a three-month, block-long illicit collaboration in San Francisco, during which Noble refined the essential elements of what he called his DROOM style.3 Whereas Slave featured thick lines defining a monochromatic gold figure, in China Basin Mural and later DROOMworks the line work became more delicate and refined, with strong 3D qualities further enhanced by skillful blending of pearlescent colors.

Noble designs DROOM pieces first as small collages, incising glossy comic-book covers with an X-acto knife, cutting along existing lines describing torqued muscles, then often following tangential lines into armor, weaponry, and the musculature of background figures, working against compositional elements of the original image. Stripped of narrative utility, all lines potentially become equally significant. Initially using an additive process, joining fragments intuitively in a search for happy accidents, Noble has also developed a subtractive process, carving an entire piece from a single source cover.

Painted in postures of confinement and powerlessness, the superheroes of Superhero Warehouse were so faithfully rendered that they remained mere emblems of resistance and identity. Noble's leap was to understand that the power and poignancy resided entirely in the inked line itself as it detailed a neck sinew twisted by the force of a punch or hypertrophied biceps flexing against tremendous pressure. His DROOMworks are similarly strained and contorted, their lines whipping violently across blank abysses, yet the pieces as wholes are strangely tranquil, almost fragile, like a stark tree branch against a winter sky, a gull hovering on an updraft, or a freeze-frame in a martial-arts film.

What reads as a Spartan helmet in China Basin Mural is actually an armored shoulder combined with plumage from an entirely different source. A detail from the frail Police Bird, recently painted on a police guard post in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, might be a lidded eye, the lens of a surveillance camera, a gun butt, or a tooled-leather holster. Referencing the iconic flourish of heraldry and the decorative symbolism of medieval illuminated manuscripts, the DROOMworks are somehow familiar yet refuse to resolve into certainty.

The DROOMworks take from comics a glamorous sheen, a color vocabulary, and a line suggesting torque; from murals grand scale; and from graffiti hermeticism and “flash.” By subverting comics' narrative specificity, murals' overt politics, and graffiti's focus on the author, Noble iconoclastically and unsentimentally reveals the poignancy of the struggles and limitations of humanity.

They are monsters in the [Mary] Shelleyan sense, cobbled from parts. Frankenstein is the title of my self-portrait, which is made the same way. From the airlessness of Frankenstein to the near-Japanese serenity of the DROOMworks, you can clearly see the virtue of releasing the parts from the mold. They don't want to make an old thing; they want to make a new thing.4

Notes

1. Christopher Hart, How to Draw Comic Book Heroes and Villains (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1995).

2. Aaron Noble, conversation with the author, December 2001.

3. DROOM is the name of a forgotten character who is technically the first modern Marvel superhero, premiering in Amazing Adventures 1 (June 1961).

4. Noble, conversation with the author.

Scott MacLeod is an artist.

Hammer Projects are made possible, in part, with support from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the Los Angeles County Arts Commission.