Hammer Projects: Jesse Bransford

- – This is a past exhibition

The ideas informing Jesse Bransford’s mural for the Hammer Museum’s lobby wall stem from the artist’s recent interest in the dialectic of liberation and control underpinning modern architecture, an ambiguous duality that he sees embodied in the monumental forms and mystical overtones of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House. In bringing together this and other imagery, Bransford’s wall drawing transforms the Hammer’s stairwell into a mythic passageway. This work can be seen self-reflexively (and more than a little ironically), as a provocative comment on the history of the museum as an image archive and a force of cultural legitimization.

Biography

Jesse Bransford was born in 1972. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. In 1996 he received a B.A. in history of the sciences from the New School for Social Research and a B.F.A. from Parsons School of Design. His work has been included in exhibitions at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in Long Island City, New York; Feature Inc. in New York; M du B, F, H & G in Montreal; and Sandroni Rey in Venice, California. This Hammer Project is Jesse Bransford’s first one-person exhibition in California.

Essay

By Claudine Isé

Filled with strange pictograms that seem to have been cut from one moment in time and pasted into another, Jesse Bransford’s paintings and drawings are a peculiarly postmodern amalgam of medieval bestiary, nineteenth-century celestial atlas, and twenty-first-century Web page. In Bransford’s art, dragons, chimeras, and other preternatural creatures cohabit with bubble-helmeted spacemen, cloaked demons and knights, zodiacal symbols, and figures from Greek mythology; flying saucers whiz past castles, pentagrams, skulls, black holes, electronic force fields, and cryptic diagrams. Drawing upon conspiracy theories, the doctrines of fringe religious groups, occult studies, and cultural phenomena such as Dungeons and Dragons, heavy metal music, 1980s-era video games, Star Trek, and Star Wars, he explores the relationship of modern myth systems to the social construction of reality.

Combining existing images with personalized icons, Bransford structures his compositions hermetically, each according to its own unique set of rules and symbols and its own system of meaning. His drawings bring together disparate images in nonlinear narrative constellations. As with myth, meaning is gleaned intuitively rather than logically, and Bransford’s viewers must interpret the queer symbols and signposts scattered about his horizonless landscapes in the manner of explorers charting vast unknown territories. The artist once described his works as "a drawn clash of esoteric belief systems";1 he is keenly interested in the methods by which subcultures, "secret societies," and other clandestine groups conjure meaning from chaos, often by jury-rigging broken bits of metaphysical machinery into vehicles for self-understanding.

The images assembled in Bransford’s 1997–99 Gestalt series of black-and-white drawings, for example, are filtered through the fictional reality of the Star Trek cosmology, which has personal significance for the artist and millions of other fans. In their schematic composition, ultra-flat pictorial space, and allover arrangement of figures and icons, the Gestalt drawings recall celestial planispheres, atlases, and other two-dimensional maps used by astronomers to plot the changing position of the stars and other heavenly bodies. Gestalt No. 12 (The Left and Right Hands) depicts the floating visages of Jean-Luc Picard, captain of the Starship Enterprise, and Marshall Applewhite, leader of a bizarre Christian sect known as Heaven’s Gate. Hoping to leave their physical "shells" behind and find redemption in a "Kingdom of Heaven" populated by angelic extraterrestrials, thirty-nine members of Heaven’s Gate committed suicide in 1997 with the intent of beaming up to a UFO that they believed was trailing behind Comet Hale-Bopp. Bransford’s fascination with this cult derives from its self-styled religious cosmol-ogy, which drew equally from familiar science fiction tropes and globally recognized brand symbols such as the cometlike Nike "swoosh" to symbolically rewrite Christian master narratives of death, resurrection, and salvation.

Other drawings mix curious illustrations from medieval treatises on science and medicine with images from pulp sci-fi, Dungeons and Dragons lore, and other symbols from the artist’s personal lexicon. Some images are easily recognizable, others less so. Most viewers will not be able to identify all of the symbols at play, nor are they meant to. Indeed, misrecognition is part of the point. Bransford’s works are encyclopedic in nature, but what is being catalogued are obsolete or cultish forms of knowledge and visual information that have lost their cultural legitimacy (or never had it in the first place). Yet the old symbols stubbornly persist, even if the meaning behind them is lost. Synthesizing symbolic forms of popular and arcane knowledge, Bransford’s drawings suggest that the modern can never entirely extricate itself from the archaic and that our visions of the future are inevitably bound up with ideas about our past and present. As new forms of knowledge arise to displace older ones, the beliefs we once held take on an increasingly mythical character. In turn, a good portion of what science takes as a given today will likely seem absurd hundreds of years from now. The compelling notion underlying Bransford’s art is that all belief systems, whether conventional or idiosyncratic, are shaped by the vicissitudes of history. His works can thus be read as allegories of the history of ideas.

The ideas informing Bransford’s mural for the UCLA Hammer Museum’s lobby wall stem from the artist’s recent interest in the dialectic of liberation and control underpinning modern architecture, an ambiguous duality that he sees embodied in the monumental forms and mystical overtones of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House. Completed in 1921, the house was Wright’s first Southern California project, and he drew inspiration for it from the forms of pre-Columbian Mexico, combining them with his own mythic interpretation of the California landscape. To Wright, the Maya temples represented might, authority, and immovability, "an architecture beyond conceivable human need."2 Integrated within the cataclysmically predisposed Southern California landscape, the Hollyhock House was intended to incarnate a dualistic vision of destruction and regeneration.

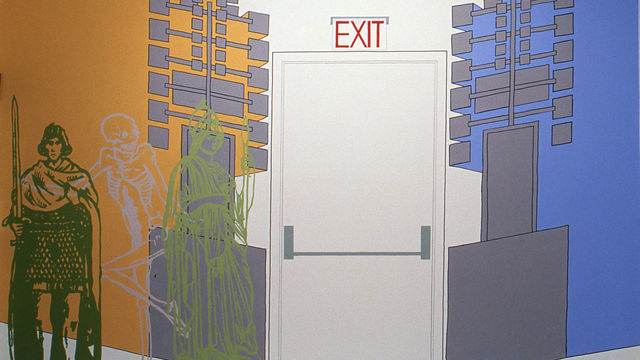

Bringing together this and other imagery, Bransford’s wall drawing transforms the Hammer’s stairwell into a mythic passageway. The vertical, geometric form that seems to project itself spatially and temporally across the expanse of the long wall is based on Wright’s Hollyhock motif, a glyph that is repeated throughout the interior and exterior of the house. In Bransford’s explorations, the glyph becomes a symbol of transition between the material and immaterial realms. He incorporates a number of other images, including a medieval woodcut portraying Death as a skeletal figure and a building composed of stacked rectangular volumes that narrow at the top. Floating above this building is a mysterious glyph that looks like an upside-down question mark. Both the building symbol and the glyph have appeared on the covers of records by Blue Öyster Cult, a 1970s-era band known for its enigmatic lyrics and mystical album cover art. The glyph is itself a reworking of both the astrological sign for Saturn (planet of difficulties, restrictions, and discipline) and the alchemical symbol for lead.

The image of the building (which is seen on the cover of Blue Öyster Cult’s second album, appropriately titled "Tyranny and Mutation"), radiates a monolithic and somewhat menacing power that embodies the artist’s own ambivalence about modern architecture, while also recalling the temple-like structure of the Hollyhock House. The fact that Bransford has selected this particular constellation of images to reside temporarily within the Hammer Museum’s walls is not accidental. His mural hints at a brutalist aesthetic lurking within the museum’s interior lobby, with its leveled planes and angled stairwell, which resonates with his own ideas about the Hollyhock House. Significantly, Bransford’s interest in both buildings lies in the mythic and symbolic associations he finds in them rather than in their "real" histories. In a similar fashion, viewers of Bransford’s wall drawing might also choose to see this work self-reflexively (and more than a little ironically), as a provocative comment on the history of the museum as an image archive and a force of cultural legitimization.

Notes

1. Jesse Bransford, interview with Hudson of Feature Inc., 1998, available online at http://www.jesse-bransford.blogspot.com and http://www.featureinc.com.

2. Frank Lloyd Wright, in Neil Levine, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996), 141, 455 n. 79.

Claudine Isé is assistant curator at the UCLA Hammer Museum.

Hammer Projects are made possible by The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Peter Norton Family Foundation.