Hammer Projects: Hany Armanious

- – This is a past exhibition

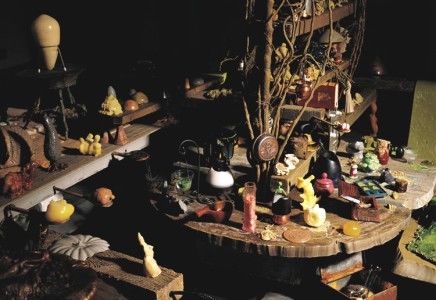

Hany Armanious’s Selflok, 1994-2001 exists somewhere between Middle Earth and the interior design of a cheap hotel. Seeing dwarves and elves in sketches he produced by stenciling the convexes and concavities of cheap wallpaper inspired Armanious to create Selflok, the ancient-mythical-modern elvish homescape depicted in his Hammer installation. An amalgam of hotmelt (an easily melted and shaped commercially produced syntetic latex), polystyrene, found objects, and other mixed media, the otherworldly Selflok, 1994-2001 bends time, space, and matter.

Biography

Hany Armanious was born in Egypt in 1962. In 1969 he moved with his family to Sydney, Australia, where he currently lives and works. In 1984 he graduated from the City Art Institute in Sydney. He has shown extensively all over Australia, most recently at the Sarah Cottier Gallery and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, and he has also shown at the Govett-Brewster Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. He has exhibited in Europe at the Thomas Taubert Gallery in Düsseldorf and the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Valmontone, Italy. In 1993 his work was chosen for the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale, and in 1995 he participated in the Johannesburg Biennale in South Africa. In 1998 he was awarded the Moet and Chandon Australian Art Fellowship. Armanious first experimented with the “hotmelt” process in 1993, during a three-month residency program at the 18th Street Arts Complex in Los Angeles. This Hammer Project marks his first solo exhibition in the United States.

Essay

By Fergus Armstrong and Amanda Rowell

The word grotto comes from the ancient Greek word for crypt, krupté. The things we call grotesque, or grottolike, are thus associated with everything we call cryptic, or cryptlike (secret codes, enigmatic inscriptions, mortuary architecture, the internment of corpses, and the memorial trappings of death). In a similarly intriguing way, the meanings of our words cosmetic and cosmic have a common origin in the Pythagorean kosmos, which specifies not only world order but also adornment, or ornament. In the distant past actual subterranean enclosures, both natural and artificial, have served in various ways as spaces of customary use and contemplative retreat having metaphoric, microcosmic significance. The half-secret etymological kinship of words that preserves this metaphoric-microcosmic complex of associations can still strike us afresh as suggestive of a corresponding, hidden structure or process at work within reality. The synonymy of grotto, crypt, and cosmos induces a fleeting premonition: what if all things are part of a fantastic grotto and mortuary vault? What if, in spite of our being normally oblivious to it, reality belongs to a kind of cavernous enclosure comprising a variety of worked-up, picturesquely nonfunctional trappings?

Hany Armanious’s installations Selflok 1994-2001 resembles the interior of a microcosmic grotto of sorts, an excavated portal giving secret access to reality. Selflok is both a theatrical re-creation of some imaginary place—an earthy laboratory or workshop, presently unattended but evidently the domain of gnomish alchemists—and an abstract, nonrepresentational ensemble of actual physical items. It seems to show the scene of the alchemical extraction of elementary, cosmetic substance while at the same time incorporating abundant samples of the extracted product in the form of congealed spills and molded bodies of gelatinous, protean “hotmelt” (a commercially produced synthetic latex). And the whole composition—precisely in its equivocally representational and abstract character—seems to lie before us as a pure exemplification of our ambiguously natural and artificial cosmos.

Within Selflok’s grotto, “artist-made” curiosities are combined suggestively with certain “found” objects so that even the latter appear as traces in which the energies of a chaotic, cosmic manufactory are congealed. The most decoratively impoverished of objects is here enchanted with the sense of having once belonged to the turbulent, molten plasticity of cosmetic earth. The merest things, whose enigmatic modesty Armanious takes such care to preserve, give cryptic intelligence of those buried interstices out of which he has apparently coaxed them. They are like ectoplasmic traces, drawn out of reality’s occulted, chaotic density via subterranean passages accessible to the artist.

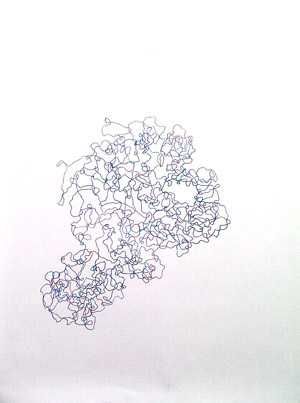

Microcosmic Selflok also serves as a fantastic, explicatory enlargement of dimensions mysteriously secluded within those “flat” material supports with which artists must interact whenever they draw, paint, or print images. This aspect of the present work is more easily accessible via description of another series of works that Armanious has produced in recent years. In 1998, during a twelve-month residency in France, he returned to figurative drawing and painting after some years of working in a more definitely sculptural mode. This return was prompted by an external circumstance somewhat beyond the artist’s control: the bedroom walls of his temporary accommodation in Hautvillers were covered with wallpaper embossed in imitation of crude plasterwork, and in his everyday encounters with this decorative surface Armanious began to “see” curious figures emerging from its amorphous low-relief pattern. Purchasing a roll of the same wallpaper, he drew on it with a pen, tracing the strange profiles articulated within or by the crevices and cavities of the textured surface. Strangely, what emerged were humanesque forms: squat, brutish hybrids and Bruegelian rustics belonging to some indeterminate, bucolic past, together with the elfin inhabitants of some imaginary “middle earth.” Apparently the encrypted materiality of the supporting surface had itself generated the artist’s will to draw and had itself produced these particular images of strange, enchanted beings. It seemed that the drawings were driven by something within a normally concealed dimension of the surface itself—that the surface possessed its own willful imagination independently of the artist but to which he had privileged access and could respond.

The diminutive Selflok inhabitants—dwarves and elves—are perhaps themselves locked into another dimension where our seemingly flat surfaces appear cavernous, harboring baroque concavities whose surfaces in turn support their own microcosmic grottos and so on, spiraling into infinitesimally small worlds. One way for the artist to access these miniature worlds is through the traditional practice of casting. Selflok is a die-casting workshop in which the ordinary field of casting is expanded to include some unconventional molds. Aramnious has captured the normally unseen cavities inside found objects, as well as the cavernous irregularities in flat surfaces, by filling them with hotmelt. The resultant “positive” convexities are always surprising, disclosing unexpected evidence of the corresponding “negative” and hidden concavities from which they were cast and of which we can have no accurate foreknowledge. He has also discovered that molten hotmelt poured into a less viscous liquid, such as water, will create quintessentially grotesque forms limited only by the cohesive properties of the hotmelt itself. Water is a mold whose internal surface, which does not exist until the hotmelt is added, is infinitely ambiguous. The water mold makes explicit how the moment of contact between the artist’s medium and the surfaces and concavities of the external world is one of concentrated, imaginative turbulence. Like the moment of emergence from Armanious’s wallpaper of those otherworldly characters, the interaction between the mold and the stuff cast permits the entry into our reality of an extraordinary and grotesque creation.

Petroleum, from which plastic is derived, is the exhumed remains of ancient forests buried deep within the earth. In Selflok, simulated wood textures are ubiquitous. Their replication in plastic—on found objects, drawn and painted expanses, and hotmelt casts—represents a fantastic return and reconstruction of wood’s own primordial surface. Further, wood grain, with its regular and pleasing design, is the archetypal decorative surface, representative of a world that is itself thoroughly decorative. Armanious uses a hot stylus to inscribe polystyrene with elaborate wood-grain designs. With these patterns we encounter a surface that is very much like that of the wallpaper he chose for his 1998 drawings. The textured surface is a potent imaginative source that, by scattering light and harboring shadow, projects phantasmal images. Normally we suppose that the power of the artistic imagination is located in “the artist’s mind.” But Armanious shows us that the artist’s gift is in being able to unseal the surface of a matter, in being able to divine and demonstrate how imaginative power resides in the surface of things.

Fergus Armstrong is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of Sydney. Amanda Rowell is an art researcher working in Sydney.

This project has been made possible by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Additional support has been provided by the New South Wales Ministry for the Arts.

Hammer Projects are made possible by The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Peter Norton Family Foundation.