Hammer Projects: Chris Johanson

- – This is a past exhibition

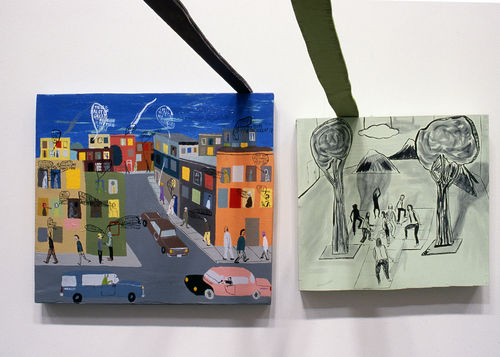

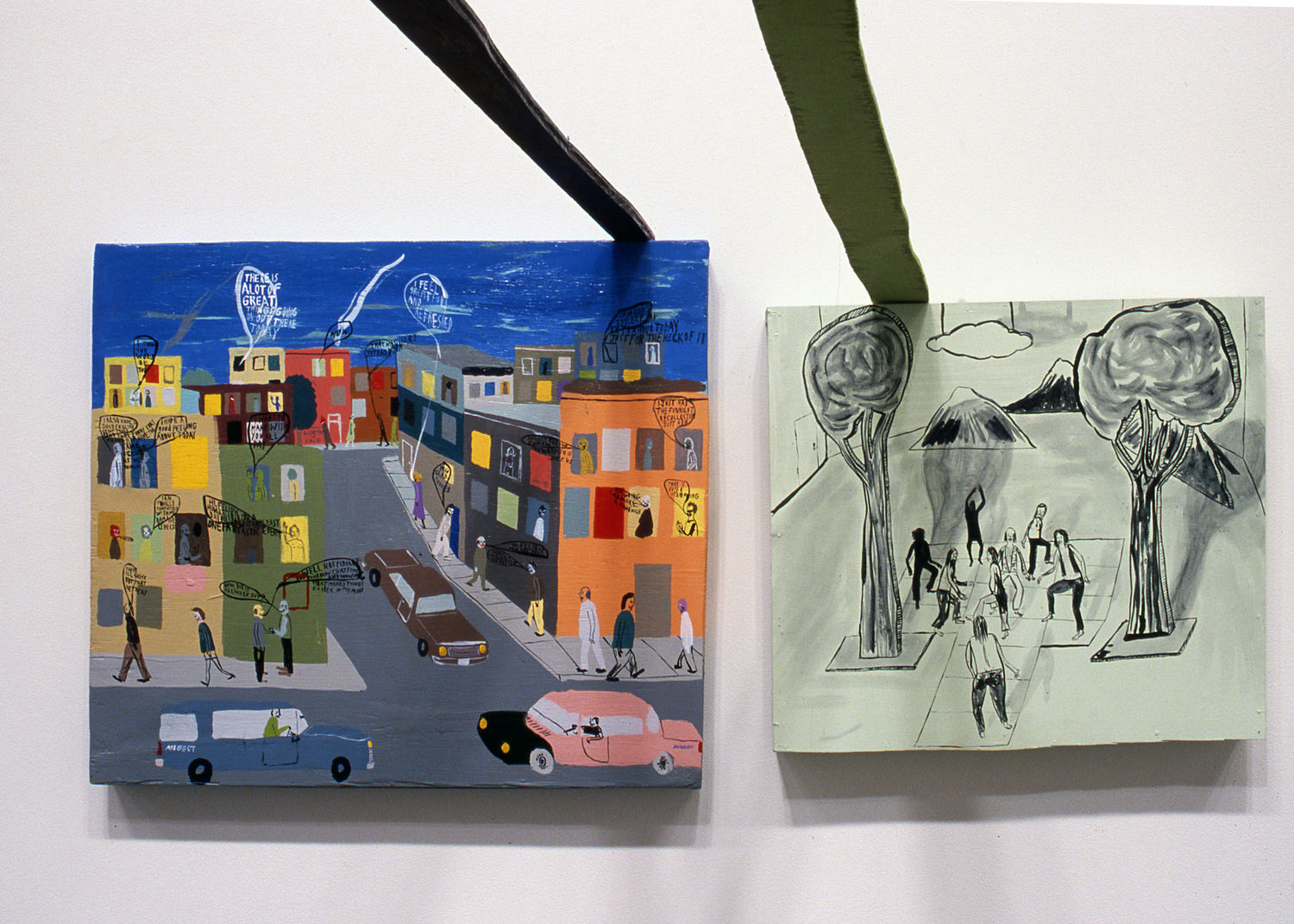

Chris Johanson works extensively in painting, drawing, and sculpture to create tuned-in portrayals of the world whose insights ring loud and clear. He combines text-and-image format to to allude to the human need for balance and harmony and point out the positive and negative aspects of city life. At the Hammer Museum, Johanson presents arrangement of individual drawings and paintings, along with his multilevel, three-dimensional dioramas depicting loose narrative scenarios. This installation presents the ideas found in his drawings and paintings in such a way that viewers can experience them more viscerally and understand his acute sensitivity of the world around us.

Biography

Chris Johanson was born in 1968 and lives and works in San Francisco. He has taken classes in history, sociology, and philosophy at various Northern California institutions. Recently he had solo exhibitions at Bodybuilder & Sportsman Gallery and Vedanta Gallery in Chicago, Alleged Fine Arts in New York, and Four Walls in San Francisco. His work has also been shown at the Purple Institute in Paris and Spiral in Tokyo.

Essay

By Julie Deamer

With every experience I expand like a balloon blown up beyond its capacity. The most terrifying intensification bursts into nothingness. . . . Life breeds both plenitude and void, exuberance and depression. What are we when confronted with the interior vortex which swallows us into absurdity? . . . It is like an explosion that cannot be contained, which throws you into the air along with everything else.1

The art of Chris Johanson is expansive. Working prolifically in painting, drawing, and sculpture, he creates tuned-in portrayals of the world whose insights ring loud and clear. A receptive viewer will recognize that what is being shared is a deeply honest and pure account of the artist's relationship to society. Viewing Johanson's work is like taking a walk around town with the artist himself as he points out the positive and negative aspects of city life. The characters that populate his paintings and drawings, and the words and phrases that enhance their impact, allude to the human need for balance and harmony. The problems that afflict people, as well as the good times in life that help it all make sense, are often presented simultaneously. The artist has said of his work: "I try to show people––happy people, sad people, angry people, people who drink and do drugs too much, business people who work too much. I try to show society as a whole."2

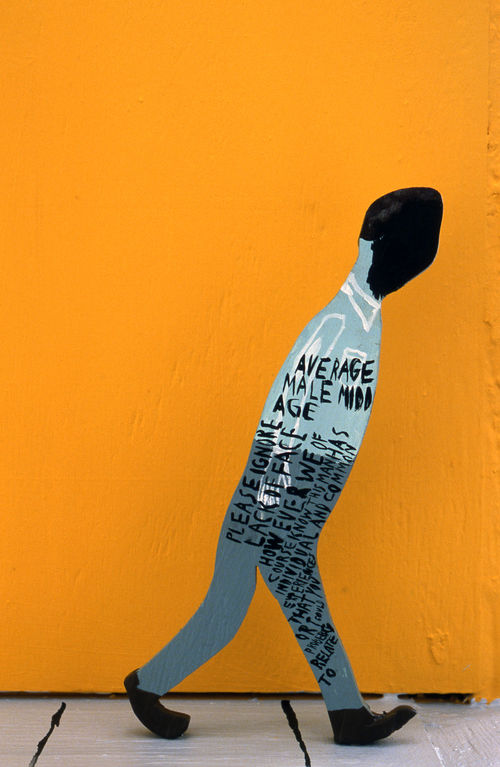

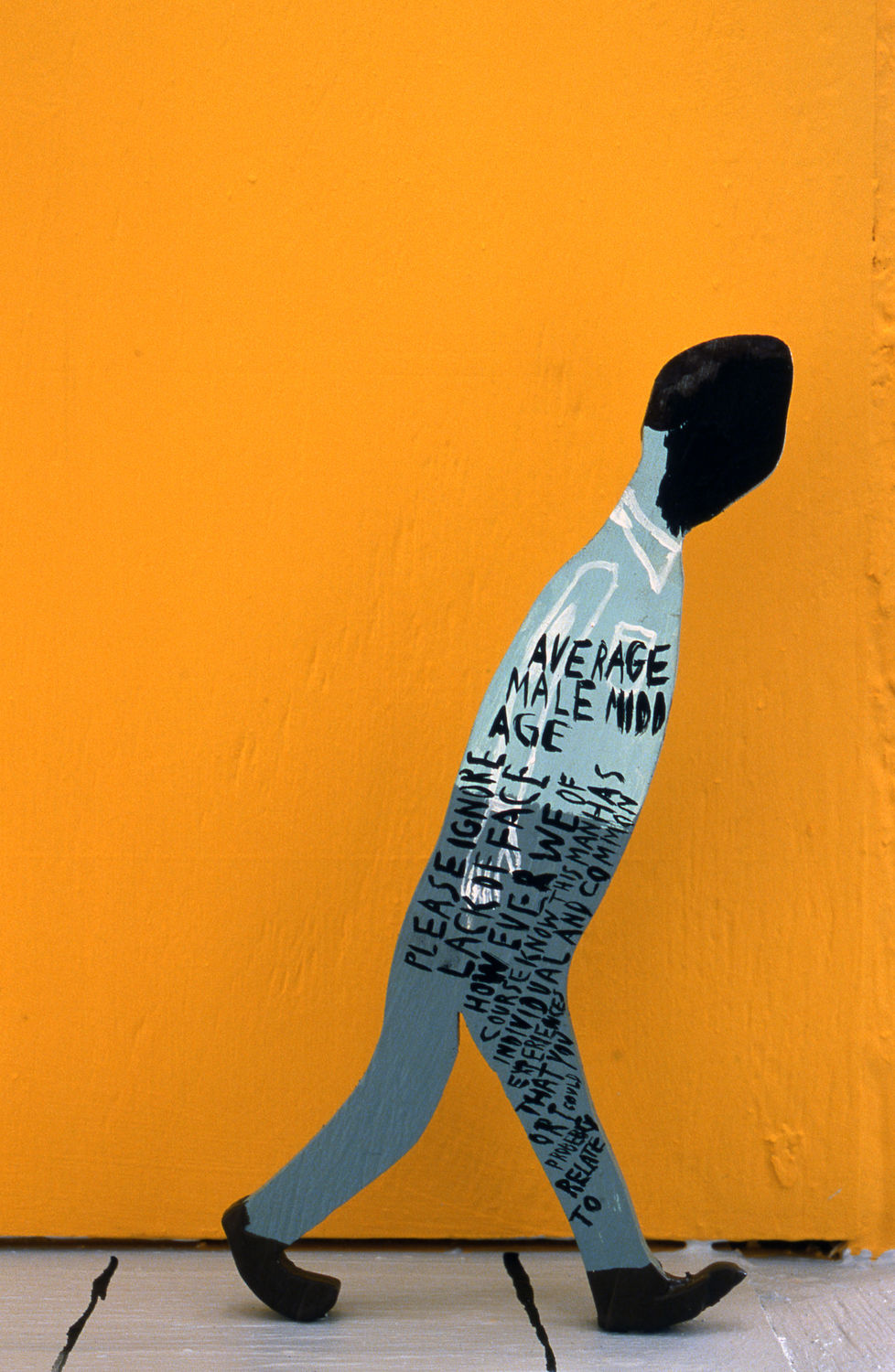

The combined text-and-image format that Johanson uses is common to many artists. His lyrical statements and expressive forms are entirely his own, and they decenter our objectivity and engage our emotions with great sensitivity and force. On irregular pieces of wood and sheets of paper of variable size and quality, he depicts social harmony alongside abject chaos. The individual works range from densely layered masses of information and imagery to sparer compositions that have only one component, represented with remarkable brevity of form and expression. This formal variety communicates a complex psychology of turmoil and stability and informs the dualistic concepts found throughout the work. With no trace of pathos, Johanson works with themes like self-delusion, alienation, drug abuse, deceit, contentment, and monotony. His understanding comes not from detached observation, but from experiencing life straight on. Never overrationalized, the work is offered as testimony to how we coexist.

Internal conflict is portrayed in many of the works. In one drawing the face of a man holding up his hand in a peace sign is covered with a scrawl of black paint. The hand is foreshortened and exaggerated, the two raised fingers elongated. The quickly drawn lines of the body convey a casual stance, but the blacked-out face makes the happy-go-lucky, universal symbol of peace feel generic, empty, even hypocritical. Other works celebrate the human spirit. Whether he is portraying a group of people dancing wildly at healing rituals or two people touching hands in an intense transfusion of love and kindness, Johanson shows us important, revitalizing moments in life. In fact, the ways in which people replenish themselves in the face of meaninglessness are at the core of this artist's practice.

Over the last several years, Johanson's installations have become less about presenting individual works and more about constructing environments. One of the first exhibitions of this kind happened in 1998 for a holiday show at the Jewish Museum in San Francisco, where the artist lives and works. Here he depicted a peaceful encampment for the homeless that riffed off the Christian Nativity scene. A wagon train of shopping carts and figures was painted onto cutout pieces of wood and propped up on a gray plywood floor. On the walls in a corner of the gallery, the artist painted a gestural gray wash with a tint of color indicating a sunrise. Telephone poles and wires were both painted onto this backdrop and represented sculpturally, with poles framing and wires hovering over the scene. The postures and resigned expressions of the figures and the overall sensitivity with which this scene was depicted elicited a deep compassion not commonly felt by viewers of contemporary art. Also in 1998, an exhibition of paintings and drawings called All on Different Trips was intensified with a sound piece of remixed Grateful Dead tunes. Created by playing two records at the same time and using a variety of effects pedals, bass amps, and mixing boards, the mix was a slowed-down and very strange rendition of the familiar tunes that have come to embody the ideals of ardent fans. Johanson brought in all of the equipment used to make this recording and, in addition, set up a microphone in the corner of the room. People’s comments and the ambient noise of the gallery were continually recycled into the mix. This sound piece captured the polar-opposite moods that you can have at a Dead concert––good times or bad times, a great trip or a really horrible trip––and certainly served as a perfect soundtrack to the exhibition’s dense social commentary.

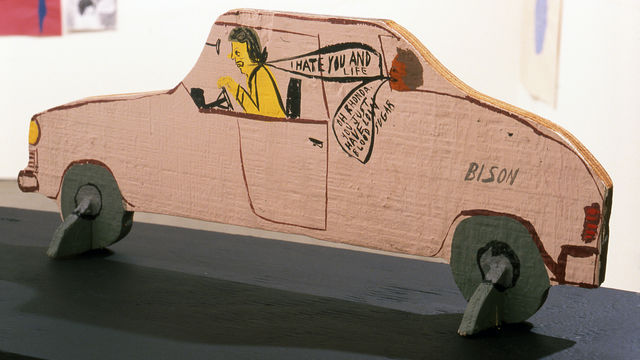

In more recent projects, such as the installation for the UCLA Hammer Museum, Johanson continues to create arrangements of individual drawings and paintings while developing his installations into multilevel, three-dimensional dioramas depicting loose narrative scenarios. One might find freeways that appear more like rickety roller-coaster tracks, crowded with brightly painted cut-plywood cars with different types of drivers––some fueled by road rage, others waving happily to neighbors. Johanson's "floaters," which represent a broad spectrum of humanity, are hung at different heights from the ceiling, suspended in a seemingly ambiguous state of either death or sleep. Landscape elements like mountains, streams, and islands stand in stark contrast to cityscapes and the narratives that are found there. These installations tweak scale and put two-dimensional images onto three-dimensional planes. By removing the negative space around the figures and elements, Johanson's installations present the ideas found in his drawings and paintings in such a way that viewers can experience them more viscerally.

In Johanson's art, the flip of a young girl's hair can convey innocence and naiveté, just as a man’s delusional stare can communicate mental instability. People coping in the face of self-hate, addiction, confusion, and alienation, as well as people surviving at the expense of others, are portrayed with compassionate veracity. Johanson's art is loaded but always direct and immediate. His ability to represent society’s ills––as well as its virtues––without cynicism results in works that impart an acutely sensitive view of the world around us.

Notes

1. E. M. Cioran, "On Not Wanting to Live," in On the Heights of Despair, trans. Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston (1934; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 8.

2. Quoted in Clare Guerrero, "Chris Johanson" (1997), published on KRON-TV’s First Cut website.

Julie Deamer is an independent curator and writer living in Los Angeles.

Hammer Projects are made possible by The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Peter Norton Family Foundation.