Hammer Projects: James Gobel

- – This is a past exhibition

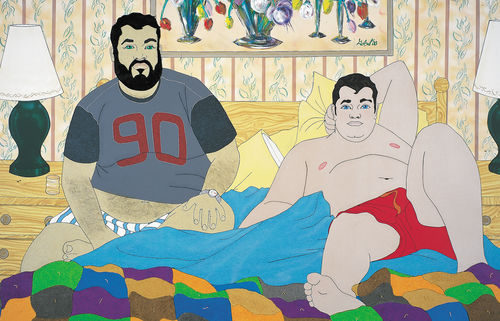

James Gobel's meticulous attention to detail and his use of felt, yarn and fabric—all supple and highly tactile materials usually associated with homemade handicrafts—imbues his gently humorous portraits with a sense of loving familiarity and intense devotion. Referencing Pop art as well as the portraits of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Gobel's paintings celebrate the unsung sensuality of heavyset men.

Biography

James Gobel was born in 1972 in Portland, Oregon. He received a B.F.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, in 1996 and an M.F.A. from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1999. His work has been exhibited at the Contemporary Arts Forum in Santa Barbara; the Museum of Art in The Hague, the Netherlands; the Liberace Museum in Las Vegas, and, most recently, at the Kravets/Wehby Gallery in New York.

Essay

By Nayland Blake

I feel fat today, and I'm glad. James Gobel's pictures make me feel glad, make me want to live in the world they present, a world of smiling fat men, shown singly or in pairs, at home, in bars, and outdoors. Meticulously constructed of yarn and felt, Gobel's pictures are at once warm and blank, homey and oddly unsettling in their single-mindedness. At first they seem to be pictures of "regular guys"—truckers, repairmen, working-class buds for the most part. They wear flannel shirts and facial hair and hang out in bars or cellars. They might all be members of the same extended family. As I look at them longer, I notice the details that lurk around the corners of the images—the logo on a T-shirt, a particular tattoo—which clue me in to the fact that something else is going on with these guys.

Like most young artists, James Gobel was able to discover what he needed to do only by first collecting a bunch of stuff he wanted to look at. That stuff turned out to be pinup magazines featuring large men: Bear, Bulk Male, Heavy Duty, American Bear, American Grizzly, Husky, The Big Ad. We can make a picture of what we love, we can make ourselves into what we love, or we can love ourselves. In 1995 Gobel deliberately made himself bigger, gaining thirty-five pounds in a month. In documenting his weight gain, he referred to Carving (1973), a work in which conceptual artist Eleanor Antin documented her own weight loss. Antin was one of many women artists active in the early 1970s whose work reinvigorated contemporary art by foregrounding issues of gender and physicality. Carving makes clear the ways in which art helps to frame our ideas about which bodies are acceptable and which are not. Many gay artists of Gobel's generation have used the works of feminist artists like Antin as templates for their own attempts to articulate a queer position in opposition to the orthodoxies of today.

Gobel went on to produce a series of works in which piles of objects stood in for the added thirty-five pounds. A group of paintings followed in a variety of materials and styles: things that initially looked like monochromatic abstractions proved to have the words chubby and bear worked into their impastoed surfaces; the walls of a suburban interior held faux thrift store paintings of depressed, chunky boys. Although it may seem that Gobel's work has moved in a contradictory trajectory, from more "difficult" conceptual work to more "traditional" paintings, this should alert us to the more difficult ideas that lurk in these seemingly traditional objects. Any artist struggles to find that place where idea and method finally work in concert. In his most recent works, Gobel has found that place.

Starting with photographs, either posed or found, Gobkes proceeds to make drawings, first in pencil and then in yarn, and then finally composes a mosaic of felt pieces. Once a piece of felt is in place, he's committed. Any mistake means having to start over. This technique makes all of the parts of the picture equally important; he has to lavish as much attention on a stone in a fireplace as on a nipple. These objects take a casual, conventional moment (the snapshot) and make it the occasion for an extraordinary act of devotion. The materials and careful crafting of these objects, the quiet planning, the piecing together of fabric, evoke traditionally feminine pursuits such as quilting, yet their imagery would most readily be called masculine.

I use the word objects advisedly, since these things only seem to be paintings. Gobel's works are certainly not the "magic windows" that we traditionally think of representational paintings as being. They do everything to insist on the impurity of their origin, the visual impenetrability of their surfaces. Their materials are not those we associate with high art. Rather they come from the world of home craft, the feminine world of dried-flower wreaths and hot-glue guns. But felt also has a history in contemporary art, linked to Joseph Beuys, who used it to represent insulation and warmth. Beuys is also famous for his use of fat as a sculptural material. In Gobel's work fat and felt are also the things that simultaneously protect and separate us from the outside world. Both his materials and his imagery combine masculine and feminine associations.

Homey in their conception, extravagant in their execution, Gobel's pictures remind us of the eager hobbyist. They appear to be more at home in someone's bedroom than an art gallery—just like their subjects, or us. Thus Gobel's practice has come to parallel his concerns.

While Gobel starts with photographs of specific people, his images are ultimately hybrids, portraying types rather than individuals. He is not concerned with the psychology of the sitter as such. This mirrors in some ways the mind-set of the men he depicts, who present themselves as both individuals and "bears" or "chubs." How do we know these men are gay? And what kind of gay men might they be?

In the late 1980s various types of gay men began to identify themselves in a new way, as "bears." They adopted some styles from straight culture, notably work clothes, and rejected what was then the gay physical ideal: youthful, muscular, and without body hair. Bears think of themselves as more real, earthier, less hung up on appearance, more accepting of a diversity of ages and body types. A subculture in the process of inventing itself needs signs, and a medium to transmit them. For bears the mediums of choice have been independent magazines, and, in the past ten years, the Internet. These forums have been the places where men separated by age, distance, language, and class have created an elaborate set of styles, behaviors, and signals that have come to characterize and international community, one that is richly inflected but that remains largely invisible to outsiders. Gobel's work draws on the imagery of this community, notably the personal ads that fill the back pages of various magazines. The personal ad makes us the advertiser, consumer, and product advertised; indeed it is an ad for our wish to consume and be consumed. But if Gobel is changing these images, if the men in his pictures don't really exist, then what are these images ads for?

Gobel's project is utopian. He believes that chubby guys have been relegated to he margins of gay life. So he places them in marginal spaces: the rec room, the basement, the rest stop, the barn, the bar, the backwoods. He is trying to make visible something previously unseen: fat gay men acting normal—that is, not out of control, not jolly, not pathetic. One of the dilemmas is that fat, by its very presence on our bodies, is wildly significant. The men in these pictures recline like odalisques, flaunting their curves. They stare directly out of the picture at the camera, at us.

Gobel's subjects know they're being photographed, but it doesn't bother them. He says that he likes showing fat men who are comfortable with themselves, and his men are not lumpy or unmanageable. Instead they are sleek, with the promise of abundance that the word zaftig implies. They stand close together. Their fat doesn't separate them; it brings them together. In the most ambitious piece here, two men lounge on a bed, perhaps in a hotel room. Their eyes don't quite converge on us, and this pair of flattened, oblique gazes brings to mind another artist whose paintings examined the place where specific depiction collapses into type: Alex Katz. Gobel's works share with Katz's a sense of leisure, an elusive psychology, and a tension between inflected and uninflected pictorial space.

Gobel says that his latest pictures are about vacations, and there is something profoundly hopeful in the way that his subjects have moved out of doors, staking a greater claim to visibility. The place where we can be ourselves in all our complexity and love freely, isn't that Utopia?

Nayland Blake is an artist, curator, writer, and teacher. His work has been shown most recently at the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York. Heis currently on the faculty of Bard College, Parson's School of Design, and Harvard University.

Hammer projects are made possible, in part, with support from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation, Peter Norton Family Foundation, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.