Hammer Projects: Barry McGee

- – This is a past exhibition

Barry McGee’s antipathy for the culture of advertising and mass-produced commodities leads him to seek forms of creative expression and communication that directly involve the hand, such as graffiti “writing,” sign painting, murals, and installations of found objects. His art evokes traces of human presence by drawing inspiration from street life and its surrounding folk culture in order to confront the absurdities of daily urban life.

Biography

Barry McGee was born in 1966 in San Francisco, where in 1991 he received a B.F.A. in painting and printmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute. Recent exhibitions of his work have taken place at The Drawing Center and Deitch Projects in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Essay

By Claudine Isé

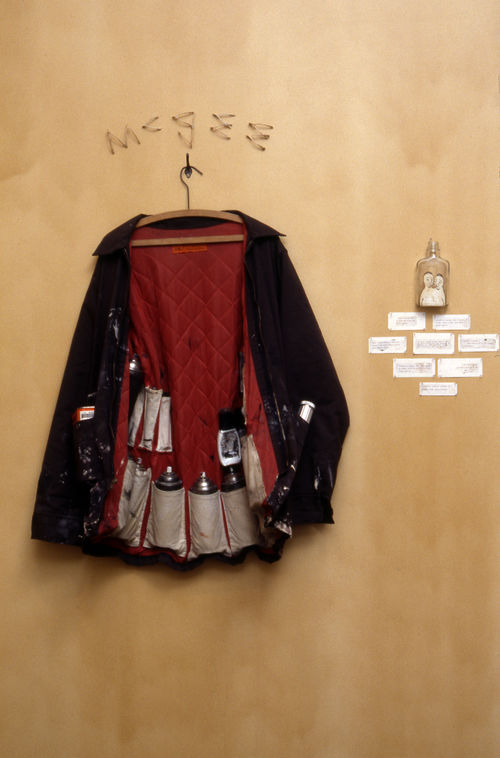

Barry McGee’s wall paintings, drawings, and mixed-media installations confront the ills and absurdities of everyday urban life. His antipathy for the culture of advertising and mass-produced commodities leads McGee to seek forms of creative expression and communication that directly involve the hand, such as graffiti “writing,” sign painting, murals, and installations of found objects that have personal meaning for the artist and his friends. Drawing energy and inspiration from street life, graffiti, punk and hard-core music, and the folk culture of tramps, train hoppers, and latter-day transients, McGee makes art that evokes traces of human presence.

Not unlike the boozily melancholic music of Tom Waits, McGee’s art conjures the humor and pain experienced by the anonymous hard-luck case who’s lost everything yet still manages to muster a lopsided smile. His signature icon is a cartoonish male figure whose unshaven face, droopy eyes, gap teeth, and doleful expression recall the iconography of the Depression-era Bowery bum, while also bringing to mind the transient, homeless population that exists in every major American city today. Sometimes McGee paints different versions of this icon onto dozens of empty glass liquor bottles. The men appear to be trapped inside, their half-grinning, half-grimacing expressions both funny and poignant. McGee’s installations often include framed snapshots of homeless men, reminding us of those who haven’t benefited from the current economic boom: witness the outstretched Styrofoam cup, gripped with trembling fingers, or the tattered cardboard placard upon which the words “Hungry. Anything will help” are scrawled in black marking pen. The transient, “tagged” by his own hand, pleads as much for recognition as he does for loose change.

McGee was born in 1966 in San Francisco, where he continues to live. For a number of years he was known publicly as “Twist,” the moniker under which he attained cult hero status among his peers as a graffiti writer during his teens. He subsequently received formal training at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he earned a B.F.A. in painting and printmaking in 1991. Over the past few years, and with great success, he has begun to exhibit his paintings and installations in prestigious commercial galleries and museums. The fact that Twist’s tags, hastily scrawled in black marking pen on building façades, are generally thought to drive down property values, while Barry McGee’s drawings and wall paintings are much sought after, is an irony that’s lost on no one. McGee lets these contradictions speak for themselves, saying only that his “indoor” work is a fundamentally different endeavor from his “outdoor” production.

Far from being a purely antisocial act of vandalism motivated primarily by the desire to deface property, graffiti writing is an essentially discursive act. It is an encrypted form of communication that is visible to everyone, but decipherable only to those who know how to read it. McGee himself has described graffiti as a lively “street dialogue” in which the built environment is subjected to an endless stream of coded messages and static interference. If the city is a text, as Michel de Certeau has asserted, then we might think of graffiti as notes scribbled in the margins. The tag marks someone’s place in the story, as if to say, “I was here, and this is how I saw it.”

The desire to leave one’s mark behind is arguably a universal impulse. Egypt’s ancient monuments are covered with graffiti, some of it left by Greek soldiers in ancient times and some left by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europeans on the grand tour. In the early part of the twentieth century, hobos etched personal monikers and emblems onto the walls and doors of freight trains. The urban graffiti culture that emerged in the latter half of the century was motivated by a similar desire to leave one’s physical trace on an increasingly alienating world.

In the 1980s artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring (who, like McGee, were also graffiti writers) drew inspiration from graffiti’s graphic kineticism, spontaneity, and defiant spirit. Even before this, in the late 1950s and 1960s, members of the Situationist International practiced acts of détournement, or “overturning,” in which preexisting aesthetic elements were reconfigured with the aim of transforming static or “dead” objects into meaningful vehicles of communication. For example, in his Modifications series Asger Jorn vandalized kitschy thrift-shop paintings, altering their surfaces by overpainting the original image with abstract shapes, words, or pictographs, just as the graffiti writer applies spray paint to buildings, billboards, or other surfaces in order to temporarily “overwrite” the city’s master narrative.

The process of moving from outside in, from the street to the gallery, therefore involves a complex range of discursive and aesthetic negotiations on the part of both the artist and his audience. McGee is not simply “translating” his street graffiti into a museum or gallery context. He insists that his indoor wall paintings are, in fact, not graffiti at all, although they are inspired and directly influenced by graffiti writing and culture. Graffiti is made quickly, under cover of night, and it is usually illegal. In contrast, McGee’s wall paintings are executed over a number of weeks. One look at the artist’s handling of fine details and lettering makes it abundantly clear that these painstakingly rendered works could never have been made on the fly. Yet McGee’s indoor wall paintings and his street graffiti ultimately share the same fate. Eventually, both will be painted over and consigned to memory.

Typically McGee’s murals are executed upon a ground of saturated red paint, upon which are layered figurative images and biomorphic forms, fringe-like drips of paint, graffiti-style tags, and words and phrases rendered in various styles of lettering. Vaguely phallic objects like cigars, neckties, bowling pins, or giant screws sometimes float within the compositional space. Sometimes McGee fills in the outlines of a man, a liquor bottle, or an empty word balloon with solid white paint, as if marking the place of someone or something that is no longer present.

Accompanying McGee’s lobby wall painting at the UCLA Hammer Museum is an untitled mixed-media installation composed of 292 individually framed drawings, photographs, and other ephemera, which have been installed in tight proximity to one another, forming a large, lopsided oval that resembles a comic-strip dialogue bubble. Each framed image suggests a thought, image, or memory that might once have passed through the artist’s mind. McGee traces his inspiration for this diaristic collection of disparate objects in part to an old church he visited in São Cristovao during a 1993 residency in Brazil. The church was filled with thousands of carved feet, legs, arms, and hands; along one wall were placed a number of small framed family snapshots and drawings. Piles of braided human hair were lined up against another wall.

McGee was struck by the depth of feeling evoked by these personal artifacts, left behind as religious offerings. His collagelike arrangement of framed drawings and photographs strives for a similar kind of intensity. The intimate scale of each work encourages viewers to slow down, come near, and scrutinize them individually. McGee’s installations sometimes also include empty bottles and spray-paint cans, wrenches, tagged street signs, and the aforementioned snapshots of homeless men. Here his accumulative method mirrors that of the street dweller, scavenging in dumpsters for something useful, redeemable. In turn, the viewer’s sustained interaction with McGee’s works brings its own form of redemption—an increasingly rare opportunity to shift one’s gaze away from the split-second blips and slick enticements of mass-media culture, and toward a direct and prolonged engagement with images and objects marked by human hands.

Claudine Isé is assistant curator at the Hammer Museum.

Hammer Projects are made possible by The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and Peter Norton Family Foundation.