Hammer Projects: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu

- – This is a past exhibition

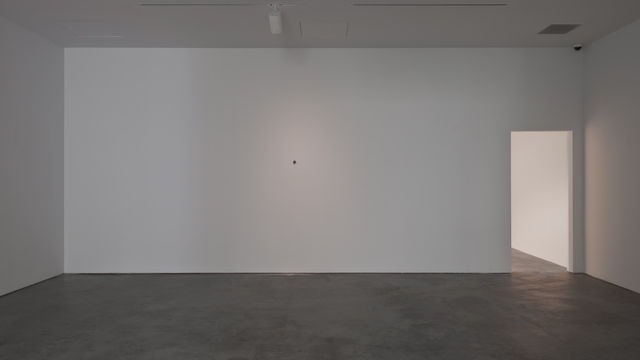

Collaborators since the late 1990s, Chinese artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu create provocative works that take as their subject some of the most compelling and complex issues of our day, from stem cell research and plastic surgery to terrorism and other forms of violence like rioting and dog fighting. Sometimes creating a direct confrontation with their viewers, their works often tap into common fears and anxieties and challenge particular worldviews. They tease out these issues by placing their viewers in the midst of strange situations: a self-propelled garbage dumpster that crashes into gallery walls, lifelike sculptures of elderly world leaders in wheelchairs bumping into one another, and a tall column comprised of human fat removed during plastic surgeries, to describe a few. The single work on view in their Hammer Project—I Am Here (2006)—grapples with the political complexities that inform East-West relations and the lingering conflicts that have deeply affected our relationship to the Middle East. By bringing these issues to the forefront, the artists shed light on prejudices and worries that might otherwise stay dormant. Hammer Projects: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu will be the first presentation of the duo’s work in the United States.

This exhibition is organized by guest curator James Elaine.

Biography

Artists Sun Yuan (b. 1972 in Beijing) and Peng Yu (b. 1974 in Heilongjian, China) both studied oil painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing. As a collaborative duo, they have had solo exhibition at the Vargas Museum, Quezon City, Philippines; Arario Gallery, Seoul; Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy; Tang Contemporary Art, Beijing; Osage, Hong Kong; and F2 Gallery, Beijing. They have shown in numerous group exhibitions including the Aichi Trieannale 2010, Nagoya, Japan; the 17th Biennale of Sydney, Sydney; the 2nd and 3rd Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, Moscow; the Liverpool Biennial 2006, Liverpool, United Kingdom; the 51st Venice Biennale, Venice; the Yokohama Triennial (2001), Yokohama, Japan; and the 5th Lyon Biennial of Contemporary Art, Lyon, France. They currently live in Beijing and this will be their first exhibition in the United States.

Essay

By Karen Smith

Now We Are All Here...

Almost as soon as they began working together in the late 1990s, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu acquired the reputation of being two of China’s most controversial artists. Since then, they have certainly produced a number of arresting projects in the name of art, using materials that frequently serve as the primary cause of the controversy. Placing a trampoline in an exhibition space, which viewers were required to use if they wished to view the artwork that had been placed in a closed-off area, was one of the least problematic—despite several fractured ankles that resulted. Their use of human fat extracted in the process of cosmetic surgery for a work acerbically titled Civilization Pillar (2001) raised the stakes. As did the use of live animals in works such as the aptly named Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003), in which dogs from the most powerful breeds were placed face-to-face on moving treadmills.

Viewers watched with stunned fascination as Staffies and boxers, pit bulls and Rottweilers, leapt at each other hell for leather. Like the character Spike, the dog made the butt of jokes in Tom and Jerry, the dogs were held in constant full-pelt limbo by the chains attached to their harnesses. That restraint provided much relief to all those present, for these breeds are known for their ferocity, and even the usually steely Peng Yu revealed a flash of nerves as she led the dogs to their stands. Oh, and then there was the tiger, in a work with the questionable title Safe Island, also from 2003. Enough said? Not entirely, for there was that early work Body Link (2000), which involved a baby cadaver, deployed to highlight attitudes toward the human condition, toward life and death, which took their practice just about as far as it was possible to imagine. But let’s not tempt fate on that score. You never know quite what the duo will be impelled to come up with next.

In their case, controversy is a good thing: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu do it extremely well because it comes naturally and not, as it might appear, because it is the focus of their intent. Looking back over the diverse works that the artists have produced in their fifteen-year career, one sees how closely they have kept their finger on the pulse of the times. Let’s face it, those times might best be described as inglorious. They have seen the introduction of cloning and controversy heaped on stem-cell research; torture as part of modern warfare; astonishing cruelty to children; a rise in gun violence, with mass shootings of innocent people in public places; social instability and rioting as responses to greed and injustice on the part of the world’s largest and (once) most respected institutions; and greater economic inequality than at any other time in history. It is not a surprise to find these topics emerging within artworks. It is surprising, however, given the climate of contemporary life, that art writers frequently feel obliged to find justification for the content of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s art. Western art history and philosophy and Chinese culture are regularly plowed to elucidate a rationale for the duo’s most controversial materials and forms. One writer invokes the West’s early practice of animal baiting, “performances by the Vienna Actionist Hermann Nitsch,” a variety of social anthropologists, and China’s own culture of “ritualistic sacrifice.”1

That doesn’t make one or two of their early works any less nasty—Curtain (1999), an installation composed of living sea life, really was—but overall, what their art achieves is actually simple: Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s work is to contemporary art what The Wire is to contemporary documentary fiction and television drama. As all good artists and great art should, they challenge our value systems, confront us with fears, prejudices, and the facts of the social conditioning to which we are all subject. They do not make reality; they simply observe it and reflect it back at us as a warning about succumbing to complacency.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu embarked on a process of thought and form that eventually led to I Am Here in 2006. It is one of a series of at least four works that pivot on hyperrealistic figurative forms, intended to prompt viewers to halt in their stride, momentarily unsure if the vision before their eyes lives and breathes and is actually part of a live performance. The first of these pieces was the attention-grabbing Tomorrow, created for the Liverpool Biennial in 2006. This consisted of sculptures of four life-size middle-aged males, which were intended to be seen floating in the Albert Dock. The fact that the figures were incredibly lifelike and floating facedown in the water prompted waves of concern, and they were removed before someone tried to rescue them.

The British public was then presented with Old People’s Home (2007) as part of the Saatchi exhibition The Revolution Continues in 2009. It was one work in an exhibition of “Chinese art” that no one could describe as “Chinese,” for it could easily have passed for the work of a young British artist. Old People’s Home consisted of several figures apparently confined by age and infirmity to wheelchairs—and to a space in which they roved like slow-motion bumper cars, unable to avoid collisions and trembling grotesquely whenever they collided. The dark humor at play here was made doubly caustic as viewers realized that these decrepit figures were simulacra of world leaders who at the height of their powers were at best dictators or tyrants, now reduced to withered, dribbling wrecks, toothless and senile. On view in another room was Angel (2008), the single figure of a “fallen” man that was so realistic, aside from the angel’s wings sprouting from his back, that his form sent hearts into mouths amid expressions of concern. While the cast of characters in Old People’s Home inspired quiet delight in seeing icons of power made all too human, the idea of a fallen angel invoked altogether more troubling sensations: you don’t have to be religious to fear apocalypse.

Like Angel, I Am Here features a single figure, one that emanates a vision that is equally disturbing, possibly of an apocalyptic nature, but for different reasons. The work consists of a hole in a wall—that’s what you see first—through which someone is peeping. To discover who that is, you are required to walk around and look behind the hole. The peeping Tom is revealed to be a very tall man, accoutered in a mix of Middle Eastern tribal dress and military garb, including American-style combat boots and an AK-47 slung over his shoulder. At the time of its creation in 2006, one such tall Islamic fundamentalist was the world’s most wanted man. The point of concealment inscribed in I Am Here mocked the game being played out in the Middle East as the entire might of a superpower was trained on capturing a single rebel leader. As we know, it was the superpower that had the last laugh, but I Am Here offers a chilling reminder of how much chaos a single individual is capable of unleashing, which in turn might serve to remind American viewers of at least one reason why China retains such control over individuals capable of causing social and political instability.

In terms of the artists’ intentions, I Am Here is part of a bigger puzzle that perhaps only a survey of their work will one day reveal with exacting clarity. Seen in isolation, the piece remains a provocative reminder of the sensibilities of the age, which continue to have profound resonance in post-9/11 America. We might take comfort, too, from the fact that while the apparent subject of the piece is in truth no longer here, we are, and life goes on, though perhaps not always as ideally as it should.

The Beijing-based writer and curator Karen Smith has worked in the field of contemporary Chinese art since 1993. She is the author of Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-garde Art in New China (Timezone8, 2008) and, most recently, As Seen 2011: Notable Artworks by Chinese Artists (Beijing World Publishing Group, 2012).

Notes

1. Paul Gladston, “Bloody Animals! Reinterpreting Acts of Sacrificial Violence against Animals as Part of Contemporary Chinese Artistic Practice,” in Crossing Cultural Boundaries: Taboo, Bodies, and Identities, ed. Lili Hernández and Sabine Krajewski (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), 96, 102.

Hammer Projects is made possible by a major gift from The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors through the Los Angeles County Arts Commission and by Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy. Additional support is provided by Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Decade Fund; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.