Hammer Projects: Mark Flores

- – This is a past exhibition

Los Angeles-based painter, Mark Flores translates the optically-driven mechanics of the photographic process into color-saturated handmade paintings. His ambitious Hammer Project will consist of ninety-nine individual paintings layered and juxtaposed across the lobby wall. Painted alternately with an expressive, brushy technique and a labor-intensive benday-like technique in which the CMYK colors of the printing process are layered upon one another in small dots, the paintings are based on photographs taken by Flores during hours-long journeys in which he walked the full length of Sunset Boulevard, both during the day and at night. The imagery runs the gamut from architecture to landscape, creating an idiosyncratic, and highly personal, map of the city that is both representational and abstracted, both historically rooted and of-the-moment, ending at the top of the stairs with a large pastel drawing of the ocean. In addition to this multi-paneled work, the exhibition will include a digital slide show of the hundreds of photographs Flores took. Flores’s cityscape serves to capture and lovingly represent the passage of time, focusing our attention on aspects of our environment that might have otherwise gone unnoticed. Hammer Projects: Mark Flores will be the artist’s first solo museum exhibition.

This exhibition is organized by Anne Ellegood, Hammer senior curator.

Biography

Mark Flores was born in Ventura in 1970 and currently lives in Los Angeles. He received his MFA in 2002 from CalArts and his BA from UCLA in 1999. Flores has had solo exhibitions at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles and Alison Jacques Gallery in London. His work was also included in group exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach; Patricia Faure Gallery, Santa Monica; California State University, Los Angeles; Golinko Kodansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Reviews and articles of Flores’ work have appeared in Artforum, Flash Art, Los Angeles Times, Frieze, and The New York Times.

Essay

By Anne Ellegood

One does not get lost but loses oneself, with the implication that it is a conscious choice, a chosen surrender, a psychic state achievable through geography. —Rebecca Solnit1

In 1973 Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader walked from dusk to dawn from the Hollywood Hills to the Pacific Ocean. This was the first part of a project titled In Search of the Miraculous, and in the second part, Ader infamously set sail alone from Cape Cod, heading across the Atlantic to Europe, a journey that he never completed. Many have called Ader’s solitary treks searches for the sublime. Certainly he was examining specific characterizations of the artist—as hero, for example, or as lone figure exploring his relationship to the world. Other artists, too, have made walks integral to their practice or central to a specific piece. Hamish Fulton calls himself a “walking artist.” Richard Long’s many in situ sculptures created during long walks also come to mind, as do Douglas Huebler’s spatial mappings of urban areas, Marina Abramović and Ulay’s walk along the Great Wall of China (1988), and Francis Alÿs’s The Leak (1995), in which he walked around São Paulo dripping a line of blue paint from a leaking can. These walks were undertaken for different reasons—political, environmental, empirical, temporal, geographic, conceptual—but each one is a portrait of a place experienced through the perspective and, moreover, the body of the artist.

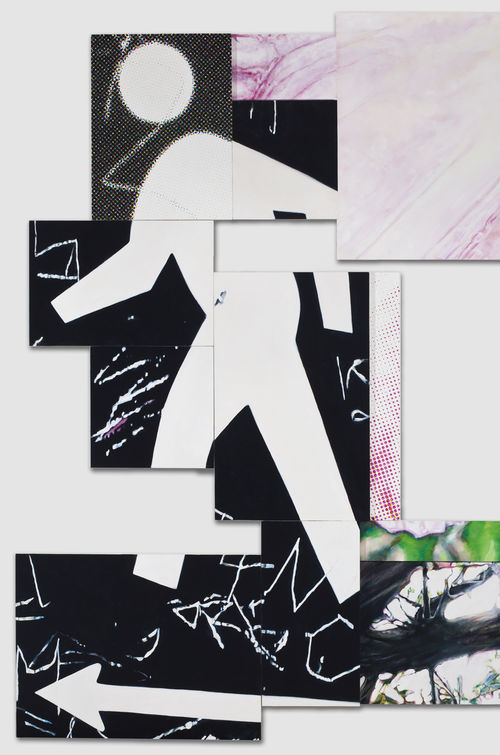

Mark Flores’s ambitious new project, See This Through (2009–10), takes as its starting point the artist’s walks across Los Angeles. For years he walked every Sunday in a different part of the city, and he has recently, on several occasions, traversed the length of Sunset Boulevard from Los Feliz or the edge of downtown to the ocean. Twice during the day and once at night, Flores took photographs as he walked the long and variegated stretch of Sunset, producing hundreds of images, which serve as the source material for the ninety-nine painted panels that meander across the Hammer Museum’s lobby walls and are also displayed as a slide show on a monitor in the space. His choice of subjects—landscapes, street signs, and architectural facades—reflects the profound intersection of the man-made urban fabric with the abundant landscape that is one of the abiding characteristics of our city.

The project is indeed a portrait of Los Angeles but hardly an objective or documentary one. Flores has called the work a “love letter” to the city, evoking some of the romantic associations that accompany Ader’s sense that Los Angeles holds the potential for the miraculous. Flores’s portrayal is deeply personal—an accumulation of fleeting views, a choreography of specific locales that caught his eye. We are seeing Los Angeles through his lens, and ultimately our view is fragmentary, just as our daily experiences of a city as vast and complex as Los Angeles inevitably are. Of the hundreds of photographs that Flores took, only a relatively small number are translated into paintings. He provides us with many details—sometimes strangely close-up and intimate views—disallowing any sense of the monolithic, or even the whole. Particular images—a tree branch; an eyeball with long, mascara-soaked lashes; twilight through the trees—are dissected and pieced back together in sections, leaving gaps of empty wall space amid the details. The result is representational paintings that nonetheless border on abstraction.

Flores has experimented with the relationship between representation and abstraction in previous works. Several multipanel installations of paintings produced over the past few years have included juxtapositions of extraordinarily detailed and precise, nearly photorealistic drawings with numerous, usually monochromatic painted panels. Some installations have been geometric, relying on the orderly grid, such as Dreamers (2006), while others, like By a Waterfall (2007), have an explosive quality, as if the abstract panels are microscopic fractals of the imagery in the nearby representation. In these works, abstraction—usually in the form of a monochrome whose color is sometimes inspired by his photographs (the pink of a sunset, for example)—was set against representation. Some of Flores’s interest in abstraction stems from his fascination with color theory, specifically the theories of Swiss Bauhaus artist and designer Johannes Itten. Itten’s approach was not strictly empirical or logical; rather he believed that intuition and personal expression must be at the heart of an artist’s practice. This balance between rationalism and mysticism can be seen in Flores’s Dream (2006), whose multiple ethereal abstract panels represent Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs’s Dreamachine, a rotating stroboscopic device used to trigger visual hallucinations. In these earlier works the imagery was appropriated—borrowed from newspapers, album covers, films, and photographic archives—and often carried associations with innovation, suffering, or pleasure, including depictions of an Alexander Rodchenko sculpture, Roman Emperor Hadrian’s lover Antinous, Judy Garland, and the symmetrical formations of Busby Berkeley dancers. In See This Through, however, representation and abstraction can embody a single canvas, and Flores’s source material has moved from the social to the personal, from the public to the private.

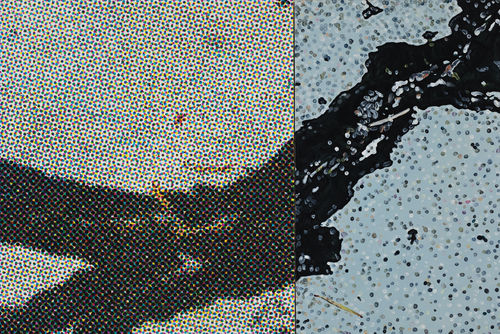

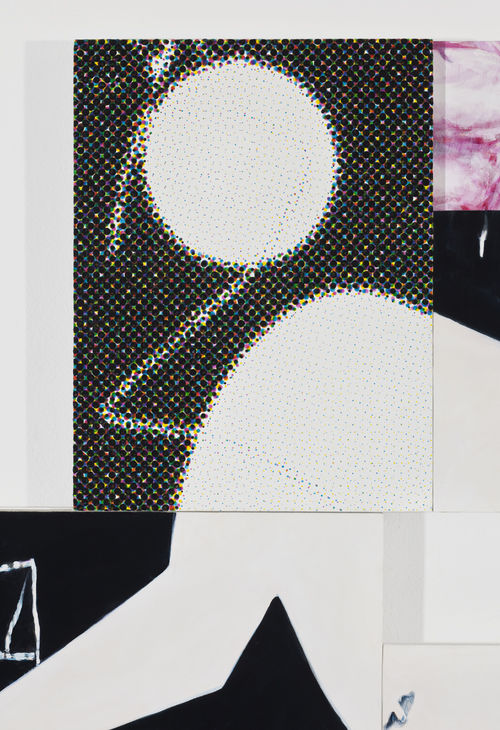

Flores has described the paintings of See This Through as “taking apart” the photographs; in them, he translates the mechanics of the photographic process into color-saturated handmade paintings. This deconstructive process prompts consideration of the way that an image comes into being, both materially and optically. It also moves the instantaneity and chance operation of the photographic act, the click of the shutter, into the realm of prolonged time, as embodied in carefully planned and labor-intensive paintings. Flores uses different painting styles for the many panels that make up the piece. Some elements are painted in a brushy, gestural style, and others in a more hard-edge, photorealistic manner. The third approach has an overt connection to the printing process. Using the CMYK colors (cyan, magenta, yellow, and key black), Flores lays down the paint with a halftone, pointillistic technique, allowing the imagery to gradually emerge from layers of dots. Both loose and tight, each painting style reads as distinct from the others, and the understanding of the imagery shifts as the viewer moves through the space. The halftone canvases, for example, are legible from a distance—the dots coalescing into a cohesive image—but dissolve into abstractions as one moves closer. Thus a work that seems deeply consumed with the image collapses upon closer viewing and becomes about the hand of the artist and the materiality of the paint.

The layering in Flores’s painting processes is mirrored in the sculptural physicality of the installation. Stacked in varying depths, the individual panels come off the wall and sit on top of one another in areas. This collage-like flurry of images is akin to the act of walking, in which one thing is continually replaced with another. The rhythm and cadence of the movement across space and the familiarity of the subject matter give way to a sense of surprise and discovery. Individual desire—in the form of monstrously large, lush flowers or the brilliant golden light through the trees—becomes evident. Flores’s choices, in other words, tell us a great deal about his relationship to the city and what captures his attention. Yet he is deeply curious about the human condition more generally, and See This Through quickly transcends the perspective of the artist as he traverses the city to reflect universal shared experiences of bodies in time and space, changing viewpoints, and the role of the subconscious. Flores is a contemporary flaneur, navigating the city with an eye toward unearthing hidden treasures within the quotidian and sharing the beauty of our surroundings with us.

Notes

1. Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost (London: Penguin, 2005), 6.

Hammer Projects is made possible with major gifts from Susan Bay Nimoy and Leonard Nimoy and The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation.

Additional generous support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Commission; Good Works Foundation and Laura Donnelley; L A Art House Foundation; Kayne Foundation—Ric & Suzanne Kayne and Jenni, Maggie & Saree; the Department of Cultural Affairs, City of Los Angeles; and the David Teiger Curatorial Travel Fund.