Hammer Projects: Tony Feher

- – This is a past exhibition

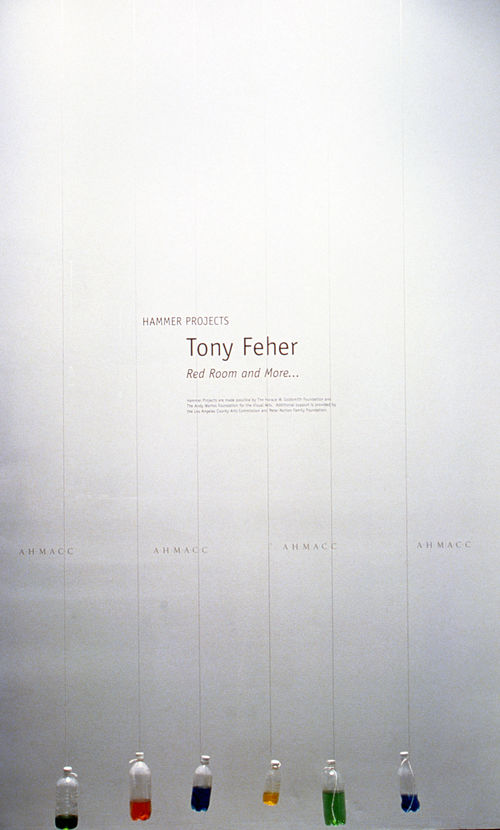

Arranging industrial and consumer products, such as lightbulbs, bottles, and thumbtacks into minimal compositions, Tony Feher creates sculptures that emphasize the aesthetic potential of everyday products. For the Hammer installation, Feher creates a new work from water filled bottles that extend from the Lobby Gallery into the Lobby.

Organized by Claudine Isé, assistant curator at the UCLA Hammer Museum.

Biography

Born in Albuquerque in 1956, Tony Feher moved to New York City in 1981 from Corpus Christi, Texas. He began showing his art in 1980, and by 1991 he was exhibiting both nationally and internationally. Recent solo exhibition venues include the Center for Curatorial Studies Museum, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York; ACME, Los Angeles; Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York; and D'Amelio Terras, New York.

Essay

By Claudine Isé

In "Le Vin des chiffoniers" (The ragpickers' wine), Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) immortalized the figure of the ragpicker, a downtrodden soul who sifted through the trash bins of nineteenth-century Paris in search of bits and bobs that could be salvaged and resold. For Baudelaire, the ragpicker's activity mirrored that of the modern poet: both existed on the margins of middle-class urban life, feeding off its consumptive delirium, and both had the uncanny ability to see in everyday phenomena something remarkable that escaped the notice of others. Like Baudelaire's ragpicker, Tony Feher sees something marvelous in the ordinary, and he has the poet's talent for making others see it too.

Feher's art draws upon the common language of disposable goods: plastic and glass soda bottles (labels removed), coffee jars and twist-off lids, metal cans, brightly colored marbles, bar straws, delivery flats, bottle caps, wooden fruit crates and plastic soda cases, pushpins, polystyrene bricks and translucent plastic grocery bags, old carpet squares and cheap plastic flowers. Suspended from the ceiling in clusters and bunches or arranged on the floor in stacks, lines, concentric circles, pyramids, columns, and other geometric configurations, the plainspoken objects in Feher's installations are quietly alluring. It can sometimes be hard to put one's finger on exactly what the difference is between the things he comes across and the work he makes as a result, and yet it is that barely discernible difference that is at the core of his art.

What distinguishes Feher's work from that of artists such as Tom Friedman, Sarah Sze, or Tomoko Takahashi—all of whom, like Feher, strive to rearticulate and reanimate mundane household items—is his extreme formal restraint and his unwavering focus on the object qua object. In a Feher piece, things are resolutely what they are; they aren't made to look like something else or juxtaposed with other objects in such a way as to make reference to some other matter entirely,. A bottle cap is a bottle cap; it does not evoke something other than itself. If anything, when seen in the context of one of Feher's accumulations of like objects, a bottle cap seems to be even more of a bottle cap than it was before.

Feher's delight in the commonplace, his focus on the concrete and the immediate, and his aversion to symbolic excess also invite comparison to the great American poet William Carlos Williams (1883-1963), who, like Baudelaire, made the stuff of everyday life his primary area of concern. William's memorable credo—"for the poet there are no ideas but in things"—finds its visual counterpart in Feher's emphasis on ordinary material phenomena, on crafting singular moments of perception, and on the absolute importance of seeing and presenting things as they are, with minimal embellishment. Williams's classic poem "The Red Wheelbarrow" embodies these ideas in both form and content.

The Red Wheelbarrow

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

The poem is itself structured like a sculpture. By breaking up the sentence into phrases, and the words into their constituent parts, Williams directs our attention to discrete components that make up the scene before us. Feher relies on similar methods of fragmentation and isolation by using repetitive patterns and building-block formations to assemble his sculptures and installations. For example, in an untitled sculpture from 1999 he stacked ten alternating red and blue plastic milk crates in an escalating column. The contrasting color scheme emphasizes the stark distinction of red from blue (not unlike William's juxtaposition of the red wheelbarrow with the white chickens), while the sculpture's interlocking structure draws our attention to the crates' functionality and design.

The sense of playfulness and simplicity that characterizes a typical Feher piece counteracts the whiff of pathos that might otherwise cling to the cast-off materials he employs. Rather than arranging a collection of brown beer bottles or multicolored jar lids in such a way as to emphasize their alienated status within a consumer-driven economy, he groups these objects in ways that emphasize their membership within a family of like objects. As a result, even an insignificant jar lid seems imbued with renewed purpose, a sense of belonging. An air of gaiety and goofy pride hangs about these items, as if even they never realized they could look this good.

Composed of three separate environments, Feher's reconfigured installation Red Room and More (2001) comes to the Hammer Museum after premiering at the Center for Curatorial Studies Museum at Bard College. For a piece titled Adam's Light (1999-2001), Feher lined a section of the lobby window overlooking Wilshire Boulevard with blue plastic bags. Sunlight streaming through this translucent membrane suffuses the lobby's interior with ambient blue light. Inside the lobby, seven rows of white-capped plastic bottles, each partially filled with water, are hung from the preexisting ceiling light grid. Hovering at ankle height inside the lobby gallery are approximately twenty-five partially filled red-capped plastic bottles, also hung from ceiling lights that appear in a slightly tighter grid formation.

The importance of light to Feher's work cannot be overstated. The subtle interaction of water and light in Red Room and More heightens our awareness of the unique qualities of the objects and space around us, just as in Williams's poem the description of the red wheelbarrow "glazed with rain / water" directs our attention to the particularities of time and place while conjuring the luminescent effect that rainwater has on an object. In a strikingly similar manner, the sparkling beads of condensation clinging to the interior of Feher's plastic bottles point to the fact that, despite their essential sameness to one another, the bottles are in a state of flux, responding to the heat of our bodies and breath and to the tiny gusts of air generated by our passage through them. And after this encounter we in turn may begin to regard the detritus of our lives differently, as things that are worthy of pause. Feher's is an art of attention and engagement, heightening our awareness of those singular, ordinary moments that so much depends upon.

"The Red Wheelbarrow," by William Carlos Williams, from COLLECTED POEMS: 1909-1939, VOLUME 1, © 1938 by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Claudine Isé is an assistant curator at the UCLA Hammer Museum.

Hammer Projects are made possible by the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional support is provided by the Los Angeles County Arts Comission and Peter Norton Family Foundation.