Turning to Art for Hope, Sanctuary, and Solace

In 2016 and 2017, I oversaw a research project on the life and work of Fred Grunwald, whose donation of prints is the foundation of the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts at the Hammer Museum. Grunwald was a German Jew who began collecting in the 1920s, only to have most of his portfolios seized in a Gestapo raid on his house in Wuppertal in 1934 or 1935. Our team of researchers combed through archival documents from the US and Germany seeking to answer a number of questions: What works were seized in the raid? Was Grunwald able to recover any of them after resettling in Los Angeles? How did this work he collected before the raid, and his experience of persecution, influence his later collecting practices? The resulting digital archive, Loss and Restitution: The Story of the Grunwald Family Collection, offers a wealth of information and documentation, but few definitive answers. The process of accumulating primary source materials into a clear and truthful narrative is a tricky one, attended by the risk of bias and misinterpretation. If there was a story I would have liked to tell—or, put another way, if there was a question I would have liked to ask Fred Grunwald—it would be about the act of collecting art as a form of resistance, and about the function of art as a salve in times of great pain. I would want to explore what he felt he lost when the Gestapo officers took those prints from his home, and what it meant to him to rebuild his collection after fleeing to America.

On this past Saturday morning, October 27, a man walked into Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and opened fire, killing eleven people. Tree of Life is in the historically Jewish neighborhood of Squirrel Hill, two blocks from where I grew up and where my family still lives. The building's Wilkins Avenue façade, adorned by an outline of the Tree of Life fashioned from metal, like a permanent shadow of the purple-leafed Japanese maple planted right in front of it, is a touchstone of my childhood; one of those images that embeds itself in the mental map of the place you're from. I played at the playground across the street, took the bus past it every day on the way to and from high school.

We are living through a time when mass shootings are commonplace, and the effects are cumulative. Watching atrocities recur again and again, it is easy to feel hopeless, even numb to them. When I read news of the shooting on Saturday morning, it was hard to make sense of these phrases—shooter, AR-15, Tree of Life, Squirrel Hill, injured, dead—in such proximity to each other. Even harder to make sense of these ideas—mass shooting, hate crime, anti-Semitism, my neighborhood, my home—in such proximity. There is a dissonance between the feeling that these tragedies are happening all the time, everywhere, and the feeling that it could never happen to you, or to the people close to you. Having it hit so close to home was paralyzing to me. I felt the need to reach out to family and friends, but I couldn't think of anything to say. Reading the news didn't help; ignoring it felt worse.

I've spent a lot of time in the days since the shooting thinking about how to process the pain I was feeling, am feeling, and how others process their pain. Knowing I'd be returning to work on Monday, I also thought about the role of art in moments like this. My friend's mother, a longtime member of a congregation that worships at Tree of Life, was asked in an interview for NPR what she was drawing upon to help her process; the first thing she mentioned was poetry. I noticed, with appreciation, that museums across Pittsburgh, including the Andy Warhol Museum and the Carnegie Museum of Art, were offering free admission to their galleries as spaces of sanctuary and solace. I recognized, as I refreshed and re-refreshed my Twitter feed, looking for news or stoking my anger or both, the brief respite that I felt when I came across posts responding to the shooting with works of art. The opportunity to change my way of thinking even for a moment, to ruminate on an image that had more to show me than horror or hate, was welcome, felt necessary.

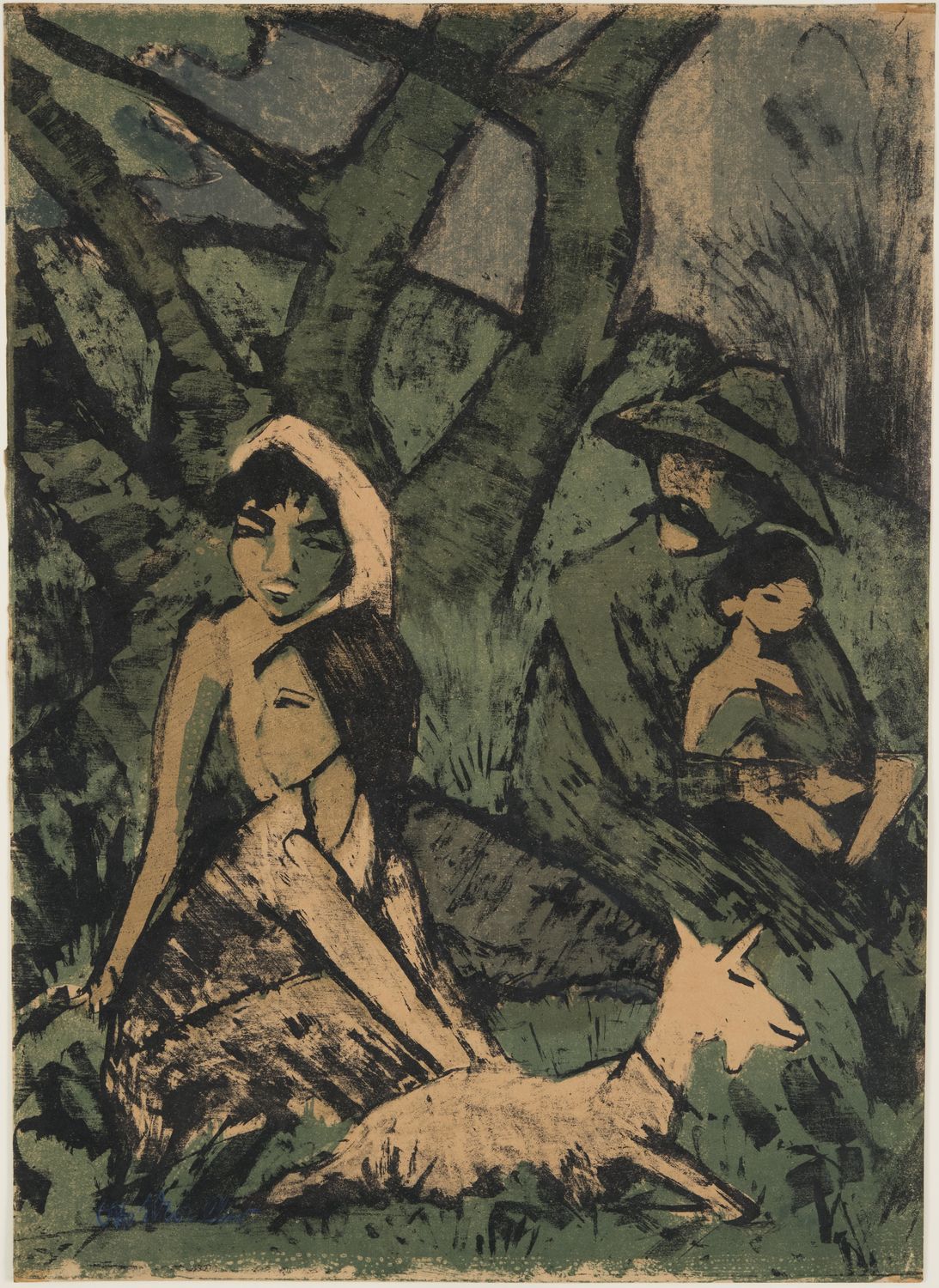

Now I am staring at Otto Mueller's austere, sympathetic lithographs of itinerant Romani (Gypsy) families, decried and banned by the Nazis as "degenerate art," which are from Grunwald's collection. These portraits, our research tells us, were among the prints seized by the Gestapo, and were among the first works that Grunwald reacquired upon returning to collecting in the US. I am searching them for signs—one child's face, at once a valediction to displaced souls and a celebration of the human spirit—that must have been meaningful to Mueller, and to Grunwald, and which may offer some perspective to me today. I am taking time to look at art, and feeling grateful the Hammer is hosting Adrian Piper: Concepts and Intuitions, 1965-2016, showing the work of an artist who takes an unflinching look at the effects that persecution, racism, and misogyny have on their victims; the exhibitions is courageous and challenging and necessary. I am heartbroken for my neighborhood, worried about my country, missing my family. I am looking for beauty and for hope wherever I can find it.