50 Years of African American Art: The Legacy of a Hammer Exhibition

The 2011 Hammer Museum exhibition Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 focused on the profound impact that African American artists had on the cultural landscape of Los Angeles from the 1960s through the 1980s. As an African American artist and student from Los Angeles, these artists and their work inspire me. When I find myself feeling hopeless about the state of the country, I look to the artists in Now Dig This!. I look to their assertions of humanity. I look to their position as people with varying interests and affinities, with a common goal to uplift themselves, their communities, and humanity through art.

Now Dig This! expanded on the legacy of The Negro in American Art, an exhibition originally presented at UCLA’s Dickson Art Center in 1966. Several artists in Now Dig This!, including Melvin Edwards, Daniel LaRue Johnson, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, and Charles White, were among the forty artists included in the 1966 show. Since the 2011 exhibition, curator of Now Dig This! Kellie Jones has continued her research in her recent book South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. In the book, Jones focuses more closely on the work of several of these artists and delves into the vibrant communities of African American artists living and working in L.A. in the 1960s and 1970s while narrowing in on the ways in which these artists engaged in activism as an attempt to bolster their own communities. The book also details ways in which these artists created space for themselves to showcase their work in the vast city of Los Angeles.

Artists Building Community

The artists featured in Now Dig This! shared a common goal: to offer the black community hope and promise as well as a rare and authentic reflection of themselves. These artists skillfully willed into existence a presence for themselves in the modern art world and the city of Los Angeles. According to Jones, they faced difficulties when they attempted to join the growing art scene in Los Angeles. Mainstream galleries and museums ignored the practices of most of these artists altogether. It was routine practice to keep “contemporary art” and “ethnic” art in separate categories, leaving non-white artists out of “standard histories.” Unable to penetrate the mainstream art scene, African American artists in Los Angeles mounted exhibitions in homes, community centers, churches, and black-owned businesses. Their collective efforts created and helped to sustain a vibrant black arts scene in Los Angeles.

Even more astounding is the fact that they did this with a network of non-black artists who also desired to move the art scene in Los Angeles, and American society, forward. To communicate this, the Now Dig This! exhibition situated these artists and their works alongside parallel developments and teased out relationships and connections between artists across racial lines. For instance, assemblages by white artist Gordon Wagner were included alongside the assemblages of African American artists Betye Saar and Melvin Edwards.

An African American Visual Language

The impact of the artists in Now Dig This! stems from their new modes of creation and invented vibrant and exciting artistic styles, which draw on their African American experience and history.

For example, an exploration of craft, and repurposing everyday materials, is part of the practices of many artists included in Now Dig This!. According to Jones, making new clothes from castoffs or flour sacks, creating new toys from old ones, and repurposing newspaper as wallpaper were skills expected of black Americans, not just for surviving in poor segregated communities, but for thriving.

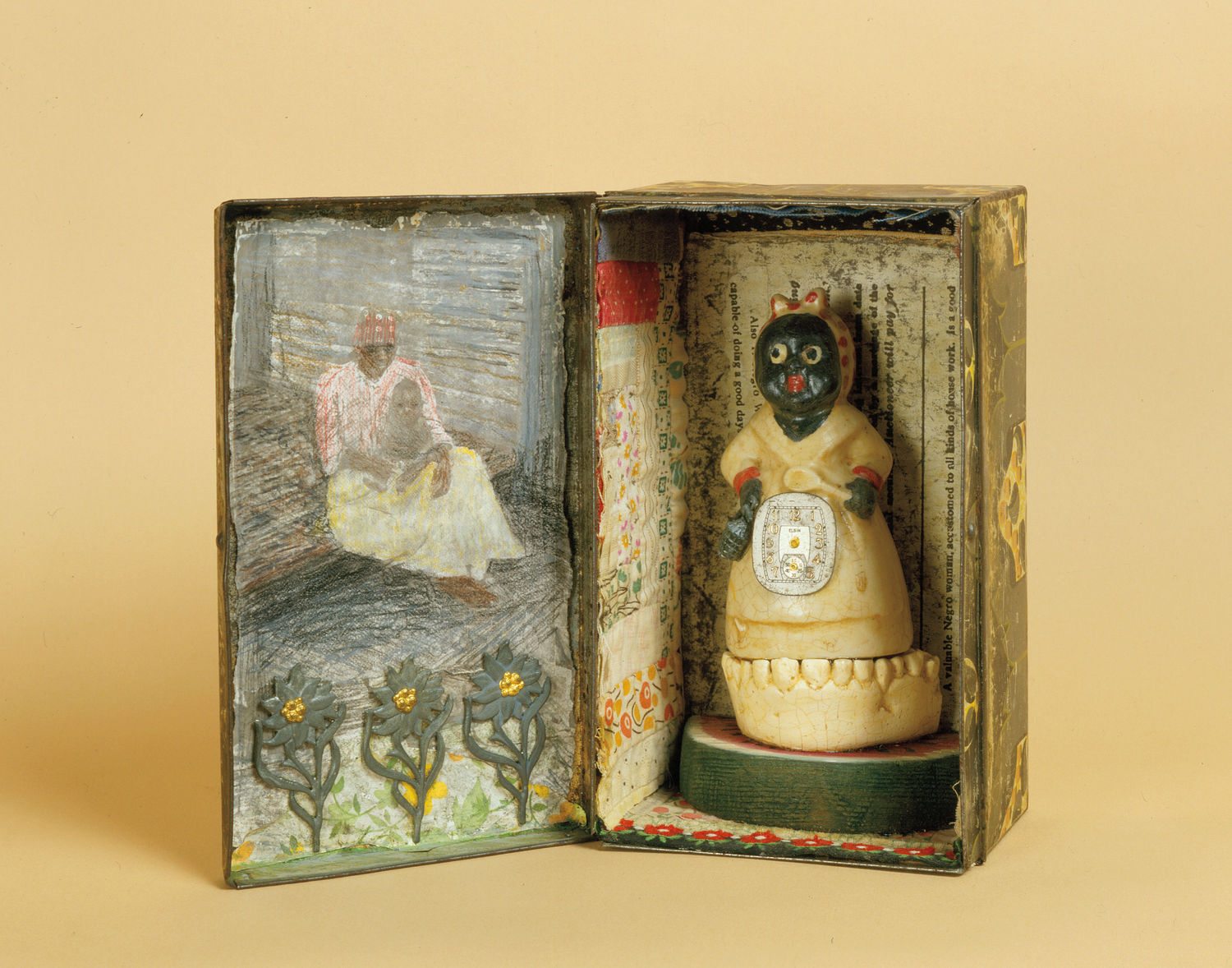

Betye Saar repurposed stereotypical figurines of African Americans whose bodies were typically either serving or performing. By reconstructing these racist images, Saar hoped to “redeploy them as their opposite” (Jones, 2017, p. 109). This was a powerful move that represented a particular aim of the black community: to take back the images and language that once defined them and create a true portrait of themselves.

An engagement with craft is also an important part of the work of John Outterbridge, who was influenced by his parents who made toys, clothes, and other goods. For Outterbridge and Noah Purifoy, assemblage offered a way to contend with black trauma and the struggles of everyday life. They both employed brilliant bold colors and pieced together materials as diverse as scraps of paper, wooden brooms, and discarded clothes. This was a means to understand and comment on society. Outterbridge poetically declared that assemblage, “has a great deal to do with the piecing together of possibilities” (Jones, 2017, p. 91).

Artists such as Charles White championed the beauty of humanity. His large-scale, sharply detailed drawings reflected on the sacred and misrecognized beauty not only of his community but of humanity as a whole. White once mused: “My whole purpose in art is to make a positive statement about mankind, all mankind, and an affirmation of humanity. All my life, I have been painting one single painting. This doesn’t mean that I’m a man without angers- I’ve had my work in museums where I wasn’t allowed to see it- but what I pour into my work is the challenge of how beautiful life can be” (Jones, 2017, p. 33).

For the artists that made up the group called Studio Z (David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Houston Conwill, and Senga Nengudi), performance offered a way to contend with memory, community and history. Their works reflected on the aesthetics and histories of the African diaspora, and their collective practice generated space for “contemplation, peace, beauty, the articulation of love, aesthetics, and resistance” (Jones, 2017, p. 6).

A Continuing History

Through the Now Dig This! exhibition, and her continuing scholarship, Kellie Jones asserts that these artists took the “dissemination of art and education of black people about art into their own hands” (2017, p. 86). The galleries, museums, and publications that told their stories were central to establishing spaces to share these narratives. Most importantly, as Jones surmises in South of Pico, the narratives they showcased annotated a small portion of the black community’s 400 year history in the United States.

Seven years after Now Dig This! opened at the Hammer, the issues these artists addressed in their work is still prevalent. Defending and asserting one’s humanity, creating space, protecting rituals and dealing with individual and collective trauma still plague this country. As an aspiring artist, I force myself to imagine my role in all of this. How do I continue to establish spaces for diverse histories and ideas to thrive? How do I communicate with people that don’t want to hear my voice? How do I uplift communities outside of mine? How do I impart that many of our experiences are shared, and that we are more alike than we are different? These are the questions that these artists were chipping away at and the questions that we all must continue to ask ourselves today.

References

Cotter, Holland. "Rebels In Paradise - The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s - By Hunter Drohojowska-Philp - Book Review." The New York Times. August 19, 2011.

Jones, Kellie. South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s. Duke University Press, 2017.

The Negro in American Art: An Exhibition/ Co-sponsored by the California Arts Commission. [Los Angeles]: UCLA Art Galleries, Dickson Art Center, 1967.