Hammer Highlights 2017: Digital Archives

2017 was a difficult year out in the world. In the warm (figuratively; the offices are always freezing) confines of the Hammer Museum, on the other hand, 2017 presented me with a much more palatable set of challenges. I oversaw the production and launch of three new digital archives, part of a series of digital initiatives funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which present artworks, historical documents, and other resources on our website so that the public can research important aspects of the Hammer's collections and exhibitions.

For my year in review post, I want to highlight some of the objects that made me smile, made me think, or otherwise helped me get through the year that was.

Corita Kent in the Grunwald Center Collection

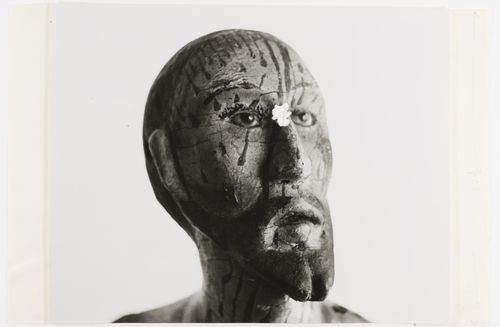

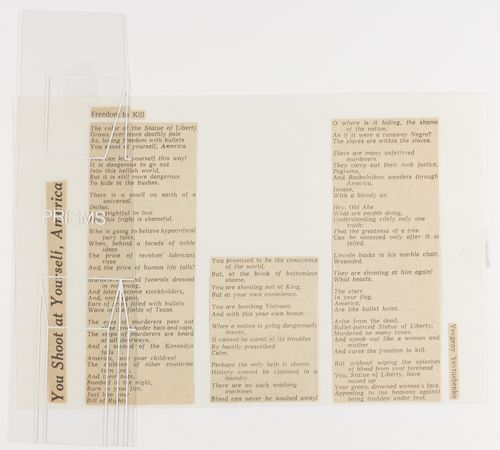

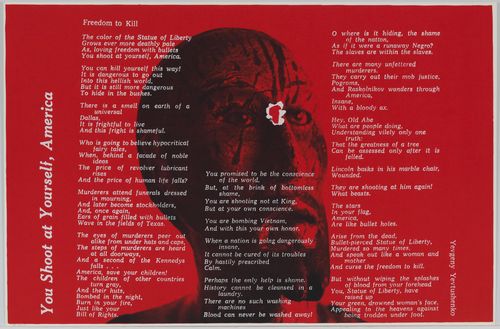

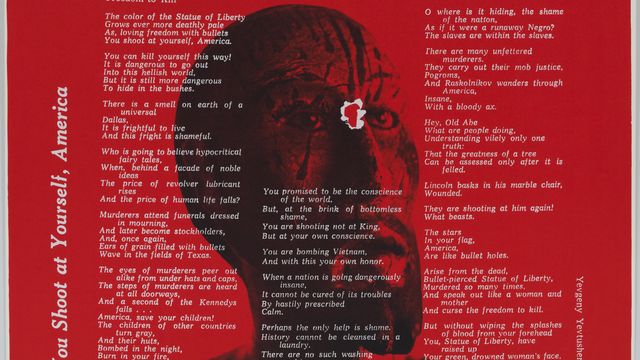

Putting together a digital archive of the work of printmaker, teacher, nun, and activist Corita Kent was a colorful process, to say the least. Her serigraphs, rendered in bright, sometimes fluorescent, hues, are a joy to look at—and a challenge to photograph, as we learned. Before the digital archive, I was familiar with Corita's prints, but had never been able to get past their vivid surfaces. Diving into the Grunwald Center Collection (housed here at the Hammer) was a revelation; not only do we own a copy of all of Corita's prints, but also a considerable collection of her preparatory documents, including sketches and mock ups with exacting instructions for the printer. Sarah Bane, the lead researcher on this project, created a page for the digital archive called "Process" where she compiled some of these preparatory materials with the finished prints. Seeing them side by side reveals the depth and complexity of Corita's work. A favorite of mine, a piece called you shoot at yourself America (1968), overlays a poem by Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko over a photograph of a statue from Immaculate Heart College's folk art collection, all on a blood red background.

The first quatrain of the poem reads:

The color of the Statue of Liberty

Grows ever more deathly pale

As, loving freedom with bullets

You shoot at yourself, America

I love seeing this work separated into its constituent parts—it helps me to see the finished print with new eyes, and appreciate the weight of its message more clearly.

Take It or Leave It: Institution, Image, Ideology

In my blog post earlier this year about building the digital archive for this 2014 exhibition, I wrote: "Living with this exhibition and these materials for two years as our team researched, designed, and built the digital archive, I found myself using Take It or Leave It as a means of gaining perspective on what was happening in the world around me." This has remained the case in the months since launching the site; in particular, I think a lot about Sue Williams's painting The Art World Can Suck My Proverbial Dick (1992).

I won't waste words trying to describe the work in detail, but I will recommend that you look at this painting in the digital archive so that you can zoom in and explore the entire canvas. If I had to describe the work in a single word, I'd say it is true. It's critical and funny and beautiful in its own perverse way and the word "proverbial" in the eponymous declaration does so many things to me. The painting is satisfyingly cathartic, and I encourage you to adopt the title as a mantra to use in times of need.

Loss and Restitution: The Story of the Grunwald Family Collection

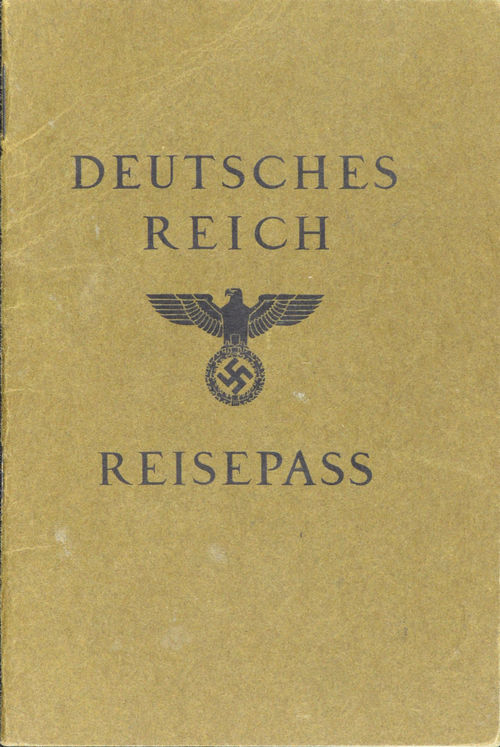

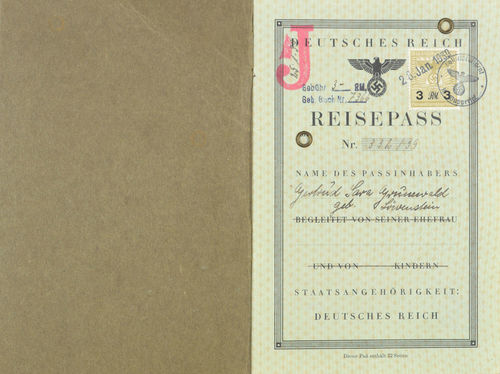

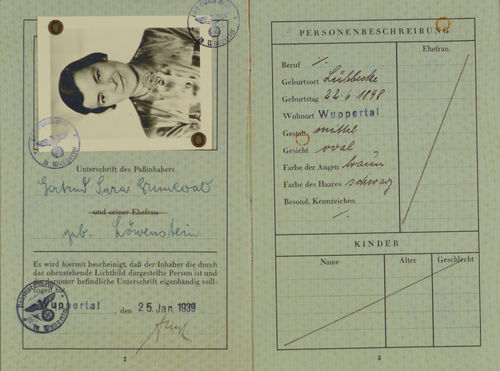

Before starting this digital archive, I knew almost nothing about Fred Grunwald aside from the fact that his name graces our collection of work on paper. Learning his remarkable story, and working on a project to tell that story, was one of the favorite things I've done in my career. Grunwald began collecting art prints in his hometown of Wuppertal, Germany, but had his collection seized during a Gestapo raid in 1934 or 1935. In 1939, Grunwald and his family fled the Nazi regime and emigrated to the United States, settling in Los Angeles. There, Grunwald again began buying prints, ultimately amassing a world-class collection which became the foundation for what is now the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. Our research team did incredible work turning up documents, from archives in Germany and United States, that helped bring the Grunwald family's story to life. One of the most fascinating documents to me was the German passport of Fred's wife, Gertrud Grunwald, which at once documents the specific travails of the Grunwald family and the experiences of Jews under the Third Reich more generally.

The passport was issued to Gertrud on January 25, 1939, a few months after an edict from the Reich Ministry of the Interior invalidated the passports of all German Jews and required that their documents identify them as Jews, separate from the rest of the German population. The red "J" stamped on the first page of the passport caught my attention, and my research confirmed that it was put there to mark her as a Jude, or Jew. I also learned that a law was passed in August 1938 decreed that the passports of Jews with first names of "non-Jewish" origin list their middle name as "Sara" (for women) or "Israel" (for men)—and sure enough, Trude's passport reads "Gertrud Sara Grunewald."

The other stamps that appear on the passport document the weeks before the Grunwald family emigrated to the United States: they tell us that Trude exchanged reichmarks for US dollars (in the amount of $4) on February 7, 1939; received an immigration visa from the American vice consul at Stuttgart on February 8, 1939; and arrived in Hamburg on February 15, 1939, from which the family set sail for New York. As an archivist by training, I'm awed by the discoveries that can arise from these seemingly quotidian records, and appalled at the manner in which evil shrouds itself in the everyday. Something to keep an eye on in 2018, perhaps.

In the coming year, we will continue to produce these digital archives. We are currently planning one focusing on artists in the Hammer Museum's collections who taught or studied at UCLA, and another documenting our exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985. I hope that you will take the time to explore and share. Students and educators in particular, we hope that you will take advantage of these resources—we made them with you in mind, and we love to hear about how you are making use of them. Happy 2018, and a good riddance to 2017!